Melbourne based writer Andrew Lawrence discusses the positives and negatives of any potential link up between Liverpool and local side Victory; do Liverpool really need such a deal?

If a recent report in the Australian press are to be believed, Melbourne Victory boss Anthony Di Pietro was in Liverpool recently to watch the reds match against Arsenal, and to discuss possible commercial and marketing links with the Anfield club.

The massive success of last July’s pre-season game, in which over 100,000 fans turned in a stirring rendition of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, and afterwards watched a practice match, has apparently made such an impression on the Liverpool hierarchy that according to ‘industry insiders’ they may be willing to expand their presence downunder.

In the wake of the recent Manchester City takeover of Victory’s local rivals Melbourne Heart, it is easy to understand the logic of the deal (or knee jerk reaction, depending upon on your view) from a Victory perspective, but would any form of tie-in with the “biggest club in Australia” be in the best interests of the Anfield outfit?

To understand the potential pitfalls you must understand some recent Australian football history.

“The biggest club in Australia”

Established in 2004, Australia’s A-League, was the FFA’s answer to the ‘old soccer’ power factions and ethnic minority groups that were seen as preventing the sport from moving from the fringes of the Australian sporting landscape into mainstream consciousness. Dubbed ‘new soccer’ the competition began with eight foundation teams, none of which were allowed to have any close affiliation to existing clubs or ethnic minority. ‘New soccer’ was to be homogenised.

One of those teams, Melbourne Victory, was granted a monopoly in Australia’s self-dubbed sporting capital, and quickly assumed, in the minds of Victory fans and some media pundits, the tag of the “biggest club in Australia.”

Sold on the back of a ‘one city, one team’ branding mantra the Victory’s marketing people appear to have tapped into some latent yearning in the hearts of Melbourne’s sporting public. In a city that adores AFL, but which hosts 9 out of 18 of the AFL teams, there was something refreshing about a code that only had one.

Victory consistently draws the biggest average crowds. Has the most members. And with two titles is the equal most successful club of the new soccer era.

Of course, all that was before the arrival of Manchester City.

The ‘City Deal’

The Sydney based FFA had high hopes for Melbourne Heart. At the time of its inception, with the success of Melbourne Victory the only real factor dragging the league into respectability, the hope was that another Melbourne club would do more of the same. With sycophantic sections of the Sydney based broadcast media going into overdrive, drawing comparisons with the Merseyside Derby to sell the proposition to a city whose only real rivalry was with the city in which the decision (and rallying cry) was being made, it was always going to be interesting to see how reality matched the hype.

So far the answer has been that quite simply, and quite predictably, it hasn’t. In the process Victory’s ‘one city, one team’ marketing pitch has been corrupted into a more spiteful, but sadly true “there’s only one team in Melbourne” terrace chant.

The problem for Heart was quite simply: how do you build an identity in a city when you aren’t allowed to tap into its ethnic subcultures and the other major club has already sold itself as the cities only team? The answer is quite simply that you can’t. Not in a city without distinct regional sub cultures (for example, Western Sydney Wanderers was able to tap into a distinctive working class area of Sydney that would never identify with local rival Sydney FC).

This is what makes the city deal is so enticing. Through its acquisition of Heart, City have brought more than football expertise to a club that is struggling (both on and off the field), they have brought a brand, and instant sporting relevance. On field performances have even improved.

For the Manchester club this is a shrewd attempt to lift its fan base in a country in which it has relatively none. Forget talk about player loans and recruiting the real point for City is that they have just bought themselves a slice of Melbourne (and Australia’s) sporting consciousness. Whether they overpaid for the privilege is open to debate however if the club is aggressive in the sports clinic area (football is the number one participation sport for children in Australia) you can bet they will generate a huge following among the next generation of football fans.

The combination of City’s high profile in elite football (and on television), local club presence through its affiliation with Melbourne ‘City’ and presumably preseason friendlies, and activity at grassroots level should pay off for the sky blues brand over the long term. While 100k crowds at the MCG seem unlikely in the near future don’t be surprised if in ten or twenty years they are rivalling Liverpool and Manchester United for Australian football affections.

The ‘Liverpool Deal’

In the weeks since the City takeover there has been a subtle shift in the perception that surrounds Melbourne Heart. While some argue that in a salary capped league the impact will be minimal, the reality is that there has already been a football power shift (and did I mention on field performances have already improved?). Not surprisingly Victory have responded.

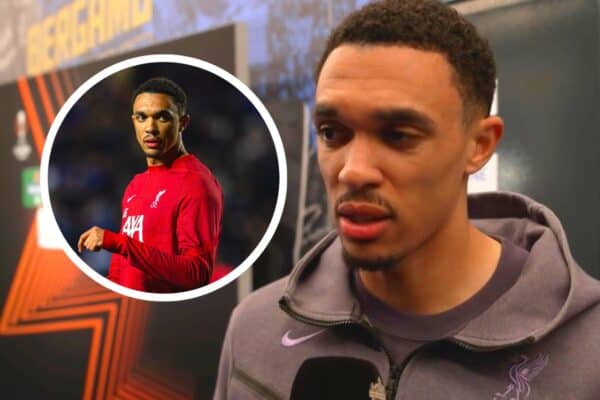

However, according to the ever present ‘industry sources’ that media pundits need to thrive, any Liverpool involvement with Victory would not follow the City model but instead would focus on commercial and marketing links. When Di Pietro visited Anfield you can bet that regular pre-season games downunder were on the agenda.

But what about other, more intimate links with Melbourne Victory?

One of the questions Liverpool should be asking themselves is why a club that was given a monopoly, and granted such fertile marketing ground, has been unable to maintain the momentum from its first two seasons. After achieving a club high average attendance of 27,728 in season two of the A League, Victory’s game attendance dropped every season until a club low of 18,458 in season six (the year local rivals Melbourne Heart came into existence). While the club has managed to grow its attendance by an average of 1000 per game in seasons 7-9, the club still has not managed to overhaul the figure from season two.

This hardly paints the picture of an organisation with marketing expertise.

More importantly, for a football club that can draw 100,000 people to a pre-season match, one has to wonder why Liverpool would need to affiliate with another club.

If the proposed links revolve around the organisation of future pre-season friendlies, and Victory are happy to become the Washington Wizards, to Liverpool’s Harlem Globe Trotters, then all should benefit.

If, however, Liverpool enter commercial arrangements that involve some blurring of brands then buyer beware. If you affiliate with a local club you take on their baggage, and Victory have plenty. There’s a local Melbourne joke that behind every Heart fan is a disgruntled ex-Victory fan. Ask any Sydney FC or Adelaide United fan what they think and you better block your ears; a reaction you won’t need if you ask them about Melbourne Heart, and most likely any other A-league club.

For me the shift towards anti-Victory sentiment occurred when the club refused to allow a friend and myself to renew our country memberships. Despite trying to renew an unusual month before this particular season started (in Australia memberships aren’t usually capped so it’s not unusual to buy memberships during the first few games of the season) we were told that a new cap applied. Victory had just signed former Kop flop Harry Kewell and were expecting massive walk up crowds. We were told that we could buy a loyalty membership that would maintain our member status but would not grant access to games. When I asked why we should show loyalty to a club that clearly had none towards us (I had followed Victory since season one and been a member since season three) the customer service rep went suspiciously quiet.

That season, the Harry Kewell factor resulted in an average crowd attendance increase of 2k, but still less than half the stadium capacity of around 50k. Hardly the epic crowds they were apparently expecting.

Rejecting loyal paying members in favour of imaginary future fans is hardly the marker of marketing competence. Whether this was an isolated incident or not is hard to say. However, when a clubs attendance at matches declines four years in a row that hints at a problem. When a relatively young football club fails to exceed its second year attendance in any season since even more so.

So, what then?

There’s no doubt that last year’s pre-season match in Melbourne was a success and should be repeated. Regularly. Liverpool FC has neglectfully ignored its Australian (and international) fans for too long, but thankfully, the club is starting to realise its mistake, and the huge opportunities that await them outside of Europe.

On the day of last season’s pre-season match in Melbourne, for example, Liverpool Football Club broke the clubs single day merchandising record. Yes, scouser faithful, that means more money to spend on player salaries, transfer fees and revamping the Anfield arena.

On my last local trip to buy Liverpool merchandise, at a Melbourne CBD store, I asked the customer service representative why over half the EPL merchandise was either Liverpool or Manchester United. He made me laugh when he observed that this was because united and pool fans were the only ones that bought merchandise all year round. It seems that local Chelsea fans only like to buy when an item is on special (oh, the irony), while Arsenal fans don’t like spending money at all. City wasn’t even on the radar.

Add in pre-season match ticket sales, merchandising, local broadcast revenue (the MCG game was on local free to air TV), football clinics and local marketing tie-ins and VIP events it’s easy to see the incentive for a regular presence down under.

Personally, I think there is huge potential for anyone who organises reasonably priced Anfield pilgrimages. Australian’s are a sports mad country, which combined with our backpacking and travel culture, has seen massive money made in sports travel packages. If given the opportunity we would travel to Liverpool, in droves. However, whether local scousers would think that is a good thing is not really for me to judge. Whether, Liverpool should link up with Melbourne Victory…

…well, as an international Liverpool member, and foundation heart member, you know my view.

Fan Comments