Marco Lopes explains why Liverpool must take 60+ points against the bottom 13 teams and concede no more than 35 goals in 38 games.

Lies, damned lies and statistics. No place for numbers in football, especially in the modern era, right?

Except that you can’t escape the numbers. I can’t recall football anymore in its ostensibly pure form, where for most of us Liverpool fans, the numbers that mattered were easily counted. 18 league titles, 5 European Cups, the desire to be number 1. Nothing else mattered.

Now, numbers have invaded the turf like a flood. The prevalence is inescapable, from the multitude of pennies envied by some of us underneath the blue balance sheets of Russian oligarchs, to those contemptuous stats underlying player recruitment by the Comolli cult.

But – in this sanguine writer’s mind at least – for Liverpool this season, only 2 numbers matter. 60 and 35.

These numbers represent 2 critical components of the most important objective of Liverpool’s season. And funnily enough, they have scale. Their achievement could mean several things for the club’s progress, all more positive than the next.

60 points. More specifically – at least 60 points achieved against the bottom 13 clubs in the Premier League.

35 goals. More specifically – no more than 35 goals conceded after 38 league battles contested come May.

Why? Read on…

A brief history of close title challenges

Cast the back room of your eyes to the closing memories of 2008-09. It felt worse than 2013-14, in some ways. The best midfield in the Premier League. The best frontman in the league. A team that didn’t know to lose easily. And yet bested by Manchester United. Again.

It’s a cruel joke that after that season, the Liverpool we hoped would rebirth instead collapsed under an incompetent incarnation of Laurel and Hardy (read Hicks and Gillett), without the wit and good cheer, and instead seasoned with mediocrity’s offspring (Purslow, Hodgson, anyone?). 5 years it’s taken the club just to recover to a season anything remotely like that one.

But since then, some interesting lessons can be taken from the wilderness that Liverpool survive in. Inclusive of last season’s tragedy and 2008-09’s bitter pill, the league has seen 2 other suffocating title races; Chelsea’s 1 point margin over Manchester United in 2009-10, and Manchester City’s Aguero inspired goal difference winner over the same rival in 2011-12, with the teams finishing level on points.

The other 2 seasons (2010-11, 2012-13) were considerably less congested at the finish line, so for that reason they’re excluded from a small analysis I’ve conducted based on a key observation made since last season when Brendan’s underestimated Reds nearly snatched the title from under Man City, Chelsea and Arsenal’s nostrils.

Flat track bullies tend to win stuff when the race is tight

For those unfamiliar with the expression of a flat track bully – it’s a cricketing term which, generally interpreted, refers to a superior opponent who only performs well when the odds are typically in their favour. A batsman who always scores runs on pitches where the bowlers get little help to create difficulty in scoring runs. A top seed in tennis who blasts his/her way past low seeds – just because they’re low seeds. And a football team with top talent that tends to beat the weaker opponents that they’re typically expected to beat.

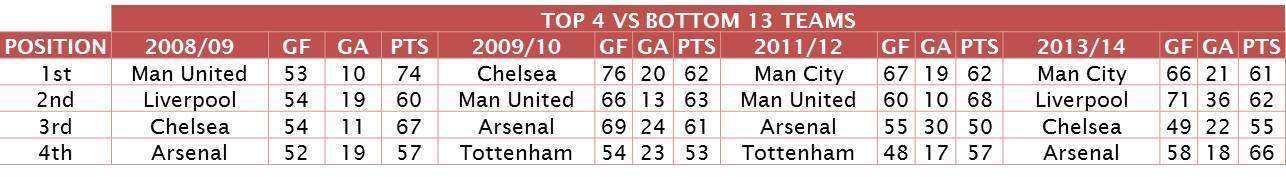

Last season Liverpool finished 2nd. And the key propulsion was the 62 points Liverpool achieved against the bottom 13 clubs, higher than their tally of 60 in 2008-09. Achieved with arguably a worse team.

This season has Liverpool fans ultimately divided in some respects in objectives. Some expect the club to elevate themselves from a 2nd place finish to their maiden title in the Premier League era. Others (like the bourgeois soul writing this) can’t trust such optimism and hence prefers to focus on the key objective being the sustaining of Champions League football in the safe womb of 4th place.

The statistically cynical would say that achieving that is very simple – get more points than 16 other teams, which is obviously true. But in planning a season, there’s a clear art and science that comes from how teams need to decide where the points ideally should come from. Particularly when the final hurdle has little margin between the runners.

Here’s the good news. If you want to finish 4th or even win the title, 60 points is a key number. The common thread amongst ALL the title winners / challengers is that they all amassed 60+ points on the way to the final weekend of the 4 seasons in question:

There’s two anomalies that stick out like sore thumbs, and they’re both largely ironic. In 2008-09, Manchester United were a very poor team against their title rivals. In contrast to Liverpool’s 14 points from 18 against the other Top 4 sides, the Mancs earned just 5 points. The big games were largely irrelevant that year, when they managed to achieve an astounding 74 from 84 points against the bottom clubs. That more than anything is what won them that league campaign.

In contrast, the small games are what largely cost Chelsea the title last season. 16 of 18 points in the big games means very little when Liverpool was beating Sunderland and Norwich in the title run in, 2 opponents that Chelsea failed to beat. Not being a flat track bully (there’s a witty irony somewhere here for the hubristic, narcissistic Mourinho) ultimately cost them the title. 55 points against the bottom 13 just wasn’t enough.

Chelsea (in 2009-10) and Man City (in 2011-12) ultimately won the title on their big game performances, keeping pace (more or less) with Man United’s return of points against the bottom 13 teams. The consistency of the number is there.

Goals win games, defence wins championships

Another intriguing (but predictable) trend of these asphyxiated title races is that teams with great defences tend to win the race. Liverpool to their credit did nearly disprove this sentiment, but there are reasons champions lose by exception rather than their own design. Teams that are dismantled systemically 5-1 and 6-0 (Arsenal) don’t win trophies. Neither do teams that gift an own goal to an impotent opponent like Hull City in a 3-1 defeat (Liverpool).

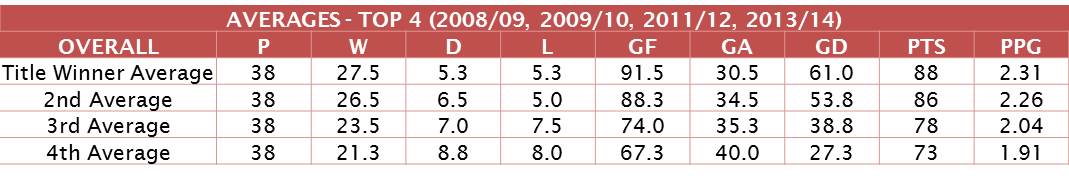

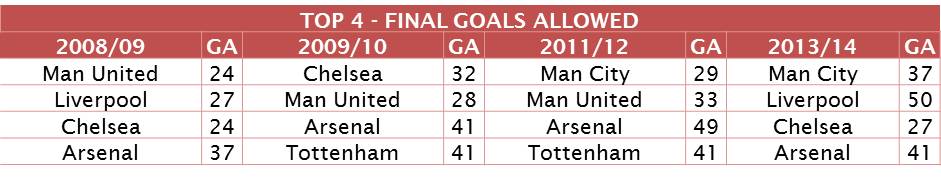

Teams that finish 1st or 2nd tend not to concede very much. Based on the sample of these 4 seasons, the average defence performs at 35 goals conceded or less:

Last season’s 50 goals conceded by Liverpool is the highest by a Top 4 finisher since Newcastle conceded 52 while finishing 4th in 2001-02. And that was in an era when Chelsea had no oil money, Everton didn’t have a decent manager, Spurs didn’t have Gareth Bale money, and Man City weren’t even in the Premier League.

This transfer window has attempted to address nearly all the deficiencies in the team’s defence in some manner. The acquisitions of Moreno and Manquillo at either fullback offer much promise to the vulnerabilities often exposed by simple crosses into the Liverpool box. While I don’t share the optimism about Lovren (more because of my prejudiced loyalty to Sakho), he does nonetheless represent an investment in the defence’s improvement, particularly in the way of leadership in the back 4. While he may not replace Gerrard immediately, the signing of Can is also a positive move in that it offers Liverpool the option of a mobile, defensively superior deeper lying midfielder or even a powerful double pivot with Henderson in tow.

But 35 is the key number. 35 doesn’t just sound good statistically – it means that it’s unlikely you need to score 100+ goals to stay relevant to the title (or top 4 conversation). And for Liverpool, in this league, that is both very possible and very achievable.

Prioritise the games you should win – and win them properly

This effectively means that for Liverpool, 60+ points against the bottom 13 teams and 35 goals conceded become the bare minimum yardsticks by which they need to plan their campaign and gauge their performance in the league table.

There’s a few good reasons for this. Firstly, Liverpool’s squad, for all it’s improvement in depth and quality of bench in this transfer window, will always be weaker as a first choice XI for the loss of Suarez. That isn’t a criticism of the spending – but rather to highlight the anchor that will hang over the neck of the team until they learn to replace the goals with a changed plan, an amended approach and adapted strategy.

3 other sides look considerably stronger on paper – but they were stronger last season too. It’s hard to see Chelsea self-destructing at key points again though, and Man City’s deep pockets have ensured they retain much of their strength to retain their title. Arsenal appear vulnerable but they have a stable and improving team running out of time to give their aging manager another title lest he becomes the next relic in the Emirates trophy cabinet.

The common sense of it (even though it’s hard to execute in practice) is that Liverpool are still considerably stronger than the bottom 13, and certainly the best poised against Everton, Spurs and the Mancs to finish in 4th. Fundamentally, even though the team may not have a first choice XI that could break through the stubborn Chelsea defence, or best the class of Man City, the point is not to focus on the big games.

There are only 6 games against the other top 4 finishers. There are 26 games against weaker opposition which have to be maximised for their full return, because that’s where the easy points are. 60 points against the bottom 13 may even be too small a target for Rodgers – his team could well be capable of achieving near 70 points against those teams, and that could be just as potent a strategy to secure top 4 and even – unlikely as it may seem for some to believe – an outside title sniff.

This is why – as an example – a slow start against Southampton was so critical to avoid. Teams that finish in the top 4 seldom have the excuse that they can have an off-day, or they’re still working to full fitness on opening day. It’s a home game against a team you should beat. 3 points. No excuses.

The other component – the defence – needs to target that 15 goal improvement to decrease goals conceded to 35. Conceding less doesn’t just mean you compensate for the loss of a goal scoring genius like Luis Suarez; it means you become far less reckless and build up a solid foundation upon which to sustainably compete in the long term. Rafa Benitez’s Liverpool in 2008-09 didn’t lack for defence ironically; it lacked goals to an extent past Gerrard and Torres. But the defence is what brought them to the title table; the final hand played unfortunately didn’t have favourable cards.

Rodgers faces the reverse situation, and I’m hopeful that he doesn’t just focus on the poor goals the team conceded in “expected” defeats to Man City, Chelsea or Arsenal. Last season, most of the goals conceded against the bottom 13 were the most revealing in the team’s defensive frailties. Frailties which sadly still look pervasive based on this season’s opening game, whether it’s down to poor team selection, or poor individual execution. If bad teams can expose your weaknesses, good teams will do that doubly so.

That’s why the improvement in goals conceded will likely need to come from the matches against this season’s version of last season’s Swansea, Newcastle, Hull, West Brom, Villa, Palace, and so forth. Because those are the goals that cost Liverpool the title in 2013/14. And without Suarez to assist (pun partly intended) in compensating for that, the points against the bottom 13 have to be won equally by a mean defence with the team’s liquid cool attacking prowess.

If Liverpool get that right, they give themselves a powerful springboard from which to explode this season. Add the team spirit, the team’s (still) underestimated quality (especially in players like Coutinho, Sterling and Sturridge), and the team’s general testicular fortitude in tough matches, and the potential for another exciting progressive season remains.

Fan Comments