A £700m bid for Liverpool FC was reportedly made earlier this year. But how much is the club actually worth? We provide an in-depth analysis using different financial models to value LFC.

Liverpool FC’s parent Fenway Sports Group reportedly received an offer of £700m from the state-backed Chinese group SinoFortone to purchase the club, with FSG said to be aware of the proposal since March this year.

While some revelations were undoubtedly embarrassing for SinoFortone, ranging from the mystery of their representative Peter Zhang using two different signatures in the space of a month, the spelling and grammar errors in what was allegedly a serious proposal, and the misspelling of Zhang’s own name, having made separate inquiries both The Independent and The Anfield Wrap were correct to note that the interest is serious, albeit highly unlikely to happen.

The motives for what is assumed to be SinoFortone or a figure at the club leaking the letter are less certain, but given the valuation placed on the club – much lower than a range of estimates provided via a number of models – there is a possibility it was designed to elicit sympathy for a takeover from sections of the fan base whose overall impression of FSG is neutral to negative, or who believe greater investment in the club than that afforded by the ownership group is needed to compete in a league in which Spurs and West Ham Utd will see their revenues increase dramatically in the near future, to add to the already well-known difficulties of competing financially with both Manchester clubs, Arsenal and Chelsea.

While FSG have no intention of selling the club in the near future, and even denied an offer had been received – semantically true, given the letter does not itself legally constitute a formal offer – it is useful to consider what sort of sum would need to be on the table for takeover discussions to even be considered.

This can be done by looking at some of the models commonly used in football or company financing to build valuations, but also it’s key to discuss the utility and flaws of those models as some are more acceptable and reliable than others.

Revenue Multiples

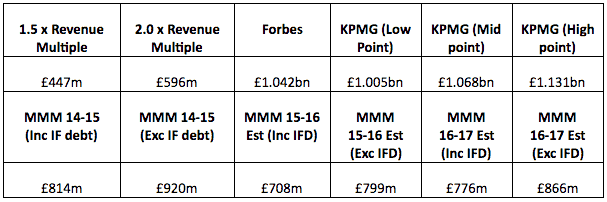

The first approach for gauging a value, a simple revenue multiple, is the most basic, and that which provides the lowest figure for Liverpool.

![LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND - Saturday, January 31, 2015: A corner flag flutters in the wind at Anfield ahead of the Liverpool versus West Ham United Premier League match. (Pic by David Rawcliffe/Propaganda) [general view]](http://thisisanfield.com/wp-content/uploads/PROP150131-001-Liverpool_West_Ham-1200x670.jpg)

Deloitte’s Sports Business Group produce the authoritative Annual Review of Football Finance, and in their 2008 edition they reported that Premier League clubs have “typically cost the equivalent of between 1.5 and 2.0 times annual revenue”.

A particular problem of this method is that it only considered the sales of nine clubs over a five-year period, a small sample size reflecting in part how infrequently they actually change hands, while it also doesn’t provide any indication of profitability among a number of other issues.

Interestingly nonetheless, it would also suggest that Farhad Moshiri’s 49.9% stake in Everton, reported to have cost £85m, would value the club at close to £170m, roughly 1.36 times Everton’s 2014-15 turnover. For LFC, these simple calculations, based on the club’s 2014-15 figures, would leave the club with a valuation of £446.92m at its lowest, and £595.89m at its highest.

Forbes

Forbes, which stated LFC was worth £1.042bn ($1.548bn) as of April 2016, uses an enterprise value (equity plus net debt) to reach that figure.

Nonetheless, there is substantial evidence that it too has priced LFC on the basis of revenue multiples, on this occasion applying a multiple of 3.5 to LFC’s 2014-15 matchday, broadcasting and commercial revenues, together with adding a vague brand value figure.

Forbes provides a valuation breakdown of $267m (matchday), $582m (broadcasting), $483m (commercial), and $215m (brand). Converting these sums to pounds, they equate to £201m (matchday), £438m (broadcasting), £364m (commercial), and £162m (brand). Divided by 3.5, this means £57m (matchday), £125m (broadcasting), and £104m (commercial), each of which either exactly or closely correspond to LFC’s revenue figures reported in Deloitte’s 2016 Football Money League.

Moreover, Forbes provides no explanation as to why the 3.5 times multiple is a legitimate method for the valuation of football clubs, as opposed to “standard” businesses, which is particularly important as Forbes’s sports business valuation figures have repeatedly, demonstrably been shown to differ wildly to the actual transaction prices.

KMPG

KPMG also uses enterprise value (defined as equity plus net debt less cash and cash equivalents) to produce what is a useful range of valuations, from the low of €1.198bn (at today’s exchange rate £1.005bn) to a high of €1.348bn (£1.131bn), with a mid-point of €1.273bn (£1.068m).

Unfortunately, but perhaps not unsurprisingly, KPMG haven’t made their algorithm publicly available, but they note the revenue multiple is derived from “acquisitions of similar companies” (what it terms a Comparable Transactions Methodology) and clubs which are publicly listed (the Comparable Companies Methodology). Happily acknowledging that this is an overly simplistic approach, KPMG then applies a variable based on a weighting of five factors, each of which has its own specific weight:

They also include a factor relating to EBITDA – which means Earnings Before Income, Taxation, Depreciation and Amortisation – a standard measure of a company’s operating performance and one of LFC’s own key financial performance indicators.

Again, sensibly, this isn’t used by KMPG in isolation as the use of EBITDA can mask deficiencies elsewhere, such as changes to working capital (the ability to fund a business’s day to day operations), while taxes and certain types of loan servicing/debt-financing are non-negotiable cash items.

While proportionate, active engagement requires more research to produce as a metric, it will indicate which clubs are reaching their fans most frequently.

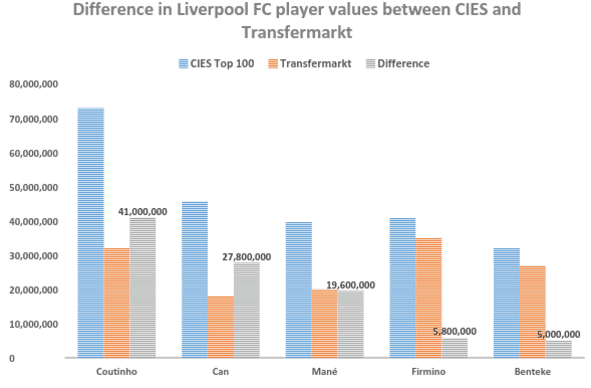

Philippe Coutinho’s worth is just €32m, while CIES’s Top 100 Transfer Values from January 2016 put a price of more than double that on his head – €72m.

Likewise, Emre Can’s Transfermarkt valuation is €18m, with CIES stating it’s close to two and a half times that at €45.8m.

New signing Sadio Mané, meanwhile, was given a Transfermarkt value of €20m (CIES €39.6m).

If the Liverpool Echo is to believed, Mané could cost as much as £34m including add-ons (€40.52m), perhaps an indication that the CIES figures are more accurate.

Indeed, accounting for the five Liverpool players included in the CIES valuation, the total difference in values is close to £100m.

In short, if these figures are reflected throughout the squad and KPMG do not account for this in their weighting, they will result in a significant undervalue, and the figure of €437.35m will actually be much higher.

The difference in player values between CIES and Transfermarkt is stark. For just five players the total difference amounts to €99m. If the CIES values are more accurate, just five players would add as much as 22.6% to Liverpool FC’s total squad value.

Discounted Cash Flow modelling

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) models are widely recognised as being very useful methods for valuing companies, but aren’t going to be considered here. For football clubs they can be problematic, as DCF models are typically reliant upon predictable future cash flows which are predominantly positive.

As football clubs have a habit of making losses – mitigated against to a certain degree now by measures such as the Premier League’s Short Term Cost Controls, which inhibit spending on wages above a certain level unless funded by non-broadcast revenue, and UEFA’s Club Licensing and Financial Fair Play criteria, which with certain exceptions limit losses to €30m over the assessment period 2015-2018, and only then if €25m of that loss is covered by a direct contribution from owners or a related-party –clubs routinely don’t have positive future cash flows to discount to today’s values.

Without wishing to get overly involved in the technical details, there’s also an underlying problem with certain DCF models in that EBITDA is used as the Free Cash Flow of a Firm (FCFF), when FCFF is arguably closer to EBIT (Earnings Before Income and Tax, but with Depreciation and Amortisation added back), together with factoring in the relevant tax rate, changes to working capital and capital expenditure.

Markham Multivariate Model

This model is particularly practical as it can do two things: firstly, provide a snapshot of a club’s worth at a time based on its financial statements at a particular period, but secondly it has merits in that re-modelling can take place relatively simply based on future financial forecasts if they are available, or if reasonable estimates can be deduced.

Moreover, the model is published and its methodology available for scrutiny, which means it is relatively straightforward to complete the calculations and to easily note any flaws, such as they exists. The formula is as follows:

Value = (Revenue + Net Assets) x (Net Profit + Revenue(/Revenue)) x (Stadium Utilisation %) / (Wage Ratio %)

This means based on the 2014-15 financial statements, where Revenue was £297.947m, Net Assets £84.294m, Net Profit £59.508m, Stadium Utilisation 98.99%, and Wages to Turnover Ratio 55.74%, the value of the club was £814.39m.

LFC’s turnover and wages have risen under separate owners, with the impact of FFP, Premier League cost controls, responsible ownership and new broadcasting deals all playing a part in restraint in wage bills under FSG.

However, we can go further still and discount the interest-free debt from the Net Assets figure to reflect the true position of the club, which in this instance is the £49.406m intercompany loan provided by FSG to fund Anfield’s expansion. On this basis, the net assets figure increases to £133.7m, and the valuation reaches £919.66m.

As noted above, the model here provides a snapshot of the past, and we should be wary of simply accepting either of these figures based on where we are today. The model itself can be impacted by one-off, non-recurring items, which is definitely the instance here, as the sale of Luis Suarez effectively accounted for the net profit recorded, and this sort of profit is unlikely to be regularly recorded, if at all.

Revenues were also enhanced by participation in the Champions League, with a regular presence in the competition an FSG objective which is yet to be achieved. Assuming that FSG will persist with revenues being continually re-invested in the playing squad, operations or facilities, the expectation is that while regular profitability will be achieved, future profits where recorded are more likely to be in the region of £10m.

Bearing in mind that the model is a snapshot of the club’s value 12 months ago, what would a “current” value be, based on the 2015-16 season, before we take into account future higher matchday and commercial revenues from the new Main Stand?

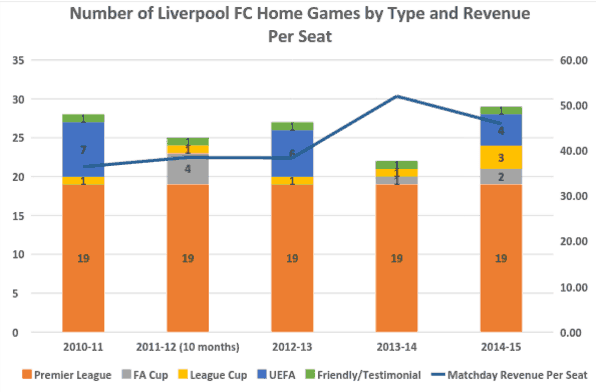

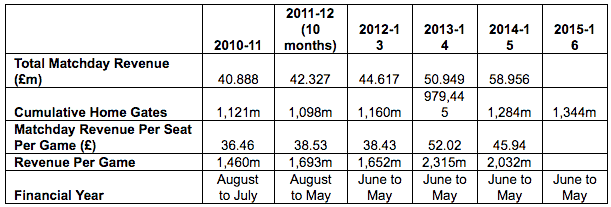

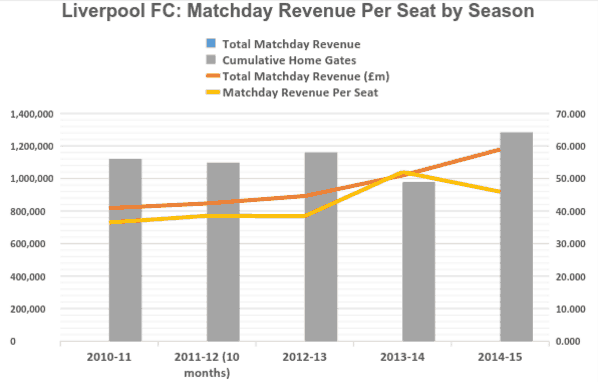

We can make a projection for overall matchday revenues in 2015-16 to be reasonably in line with 2014-15, based on ticket prices being frozen across season tickets and general admission prices, and that 19 league games, two FA Cup and three League Cup games were played at Anfield in both seasons. The only numbers that differ were four Champions League games in 2014-15 plus one friendly, compared to seven Europa League games in 2015-16.

Assuming the significantly cheaper prices for UEL games compared to the UCL were replicated across match break and hospitality offerings, overall matchday revenue should be similar, and as a result approximately £60-£62m is anticipated. Working on the basis of £46 revenue per seat per match, the figure in 2014-15, across total cumulative gates of 1,344,235, it equates to a 2015-16 matchday revenue of £61.8m.

Matchday revenue per seat is typically higher in season in which a smaller number of cup games are played, reflecting pricing by competition.

Matchday revenue per seat per game has risen since FSG completed the takeover in 2010. This will rise again in 2016-17, largely on the basis of the 4,500 hospitality seats in the new Main Stand.

The relationship between total matchday revenue and matchday revenue per seat is shown here. Matchday revenue per seat typically falls in seasons in which large numbers of cup games are played, reflecting the reduction in ticket prices/demand.

Premier League broadcast income in 2015-16 was £92.78m, down just £2.3m on 2014-15 despite the inferior league result. While the club was completing in the less lucrative UEL compared to the UCL in the previous season, the larger number of European fixtures, together with the increases in UEL prize money and the market pool should again only result in a small decrease.

For example, LFC’s total UEL prize money was €11.35m, actually a small increase on the €10.8m received in 2014-15, and with the market pool for 2015-16’s UEL being an estimated €153m, a roughly 83% increase on the previous year, LFC look set for an estimated further €19m in market pool payments, making a total of approximately €30m in UEFA revenue, only €3.6m (£3m) down on the previous year. This provides a total estimate of £117m in broadcast revenue, a minor decrease on 2014-15.

Commercial income is more difficult to estimate given the paucity of reliable, accurate information publicly available on deal values, but importantly for LFC a number of global deals began or were extended for the season, with New Balance, Nivea and MBNA seeing terms retained or improved, and public evidence suggests no major deals ended in the 2015 season which weren’t replaced like-for-like. On this basis, a reasonably conservative estimate of a 6% increase has been used to produce a figure of £123m for commercial revenue.

Taken together, this provides a projection of total revenue for 2015-16 in the region of £302m, a slight increase on 2014-15’s turnover. With a suggested net profit figure of £10m, and all other items being equal, this would result in a “current” valuation of £708m, and with interest-free debt excluded this rises to £799m.

Nonetheless, the “current” figure does not take into account what are effectively concrete financial expectations for the 2016-17 season, with enhanced matchday revenues guaranteed from the expansion of the Main Stand, and highly likely enhanced commercial revenues upon the conclusion of a naming rights deal.

Chief Executive Ian Ayre expects £20m to be delivered via the additional 8,500 seats, which would be £2,352 per new seat over the course of a 19 game season, or assuming 22 home games including a small number of cup ties, £106 per game per each new seat, a figure heavily influenced by the 4,500 corporate seats.

This suggests that effectively LFC are expecting minimum total matchday revenues in the region of £70m for 2016-17, given matchday income was £51m in 2013-14, the most recent season without European football and of relatively similar ticket pricing.

The new Premier League broadcast deal is also likely to add approximately £50m to LFC’s bottom line, and it’s entirely reasonable to conclude that £140m in broadcast revenue will follow in the coming season.

As for commercial revenue, while a number of deals have ended this summer, notably among them a number of major or principal partners such as Garuda Indonesia, Jack Wolfskin, Gatorade and Vauxhall, major deals began or were extended with BetVictor, Maxxis, Skype, DraftKings, Standard Chartered, Vixlet, and Chaokah, while the expectation is that a naming rights partner will deliver between £5m-£9m per year.

As such it’s relatively likely that LFC will see its sustained commercial growth continue under FSG continue into the 2016-17 season, and it’s not unreasonable to consider a total revenue estimate for 2016-17 of £340m – based on £70m matchday, £140m broadcast, and £130m commercial – highly conservative.

Using this figure and again factoring in certain conservative assumptions, this delivers an estimated value of £776m, which excluding interest-free debt climbs to £866m.

Making certain assumptions, including enhanced on-pitch and corresponding commercial performance, it’s entirely reasonable to conclude that a valuation of £1bn using the Markham model is feasible within the next couple of seasons, if not in 2016-17 itself.

So which figure is correct?

Perhaps it’s not so important to discuss which individual figure is correct, so much as to agree that, even bearing in mind the flaws of certain models, the figure placed on LFC by SinoFortone is almost certainly a major under-valuation, and in pure business terms was correctly given short shrift by FSG.

A conservative estimate of LFC’s value at the end of the 2016-17 season is £866m, with other models suggesting figures of £1 billion are appropriate, and as such an “offer” of £700m would invariably be treated as desultory.

Moreover, FSG, unlike the Glazers, are keen to stress that no money is taken out of the football club, and while the wisdom of certain player investments and strategic decisions can be queried, at the very least it’s clear that those monies are reinvested in the football club.

FSG’s “investment model” effectively relies upon rising but sustainable expenditure set against a long-term strategy of revenue growth across all income streams, lately buoyed by the growing attraction of Chinese investment in football in general and the English game, to deliver a significantly increased sale price as and when they choose to exit, not short-term profitability.

Given the possibility of further increasing Anfield’s capacity to close to 60,000 exists, for which outline planning permission has already been granted and for which the demand is well-known, and with Andrew Markham, the club’s Head of Global Partnerships describing the SAIC/MG deal in China as the “cornerstone of LFC’s future strategic development” and China being a key market in which the club is seeking to capitalise, it seems very unlikely that FSG are interested in a sale in the short-term unless a much more substantial offer than £700m is made.

Interestingly, the sharp drop in the pound following the EU referendum could make English football and investment in the club more attractive, whether from a naming rights perspective or in terms of an outright purchase. For example, on 10 February 2016, the date on the SinoFortone letter, £700m was the equivalent of ¥6.682bn (1 GBP = 9.5469 CNY). At today’s rates (1 GBP = 8.8412 CNY) the same sum of ¥6.682bn is worth £756m. Likewise, if a Chinese bidder had put a bid ceiling of ¥8bn on 10 February, at the time this equated to £838m, whereas today it’s £906m.

Despite these words being used interchangeably, it’s worth remembering as fans that there’s a difference between price (what someone actually pays for a product), worth (what the product objectively could/should have been sold at), and value (how important that product is to someone subjectively and emotionally).

An offer of £140,000 or £160,000 might be accepted for a house purchase when it was actually worth £150,000, and its value, based on its subjective importance, may differ again. Likewise, whether Liverpool FC is worth £700m or over £1 billion, and whatever the future transaction price actually is, we don’t discuss a club’s value in terms of money.

The value to us is in all the shared experience that a club brings, whether joy or misery, the songs, the togetherness, the matchday routine, the (mostly false) transfer rumours, the baiting and mockery of other teams, players and managers, and much more besides.

What needs to be ensured is that value isn’t diminished in any way, which is why the aspect of how any future purchase is funded is of such great importance – for example, not by loading unsustainable debt against a holding company and attempting to use club revenues to service it.

While FSG have their critics, and some criticism is deserved, they’ve helped restore the club to health, sustainable growth, and profitability. And there’s value in that.

Fan Comments