Football may not be widely known as a ‘tough’ sport. That is, not by those who have never played the game. But, there have been lots of tough guys and hard men over the years and Liverpool have had a few of their own. If you were to ask who was the hardest of them all, the usual answer would be Tommy Smith. He was known as the ‘Anfield Iron’ for good reason, but in fact that was more by reputation than anything else. In fact, if you ask that question of most of the players themselves from the early sixties onwards, they’ll tell you without doubt that it was Gerry Byrne who should claim the title as the hardest. But, you don’t have to take my word for it; Tommy Smith gave an interview on Shankly.com where he tells this anecdote from 1960:

I was only fifteen and playing in a five-a-side game at Melwood. I nutmegged Gerry Byrne and scored and I was on top of the world. A couple of minutes later a ball dropped between us, I went to head it and Gerry headed me and I went down with a gashed eye. As I lay on the ground covered in blood, Bill Shankly strolled across, looked down at me and said: ‘œLesson number one, never nutmeg Gerry Byrne son and think you can get away with it.’

As with many young players of that era, Gerry Byrne joined Liverpool straight from school at age fifteen in 1953. Don Welsh, who was the manager at the time, signed him as a professional the day after his seventeenth birthday, on August 30th, 1955. He made his debut (and only appearance for that season) on September 28th, 1957, with a 5-1 loss at Charlton Athletic. After that, he played a mere 7 games over the next 3 seasons, and was on the transfer list when Bill Shankly arrived, taking over from Phil Taylor in December of 1959.

Fortunately for all of us, and especially for Byrne himself, Shanks saw qualities in his play that others had missed. Instead of being transferred, Byrne became an integral part of the team that Shanks was building to finally take Liverpool out of the Second Division – and beyond. Left back Ronnie Moran was out with an injury when Byrne was given his chance, and he kept the position as his own from then on. His grit and determination were on display in every match of the 1961-62 promotion season as Byrne was an ever-present in all 42 League matches (as well as all 7 FA Cup matches) with Liverpool finishing a comfortable eight points clear of second place.

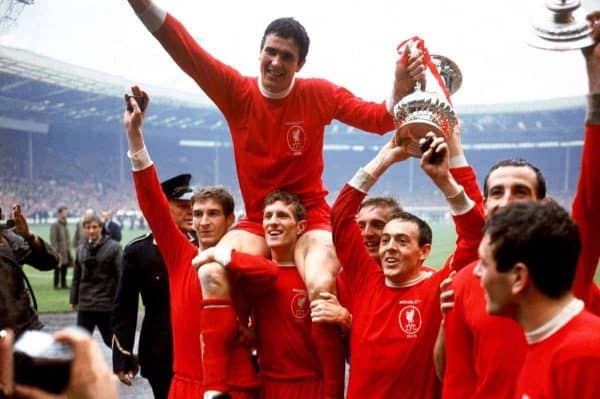

The first season back in the top flight saw Gerry Byrne play 38 of 42 League games (and all 6 FA Cup games) as Liverpool finished respectably in eighth place. It was only one year later when the First Division title was won, and one more season after that when Liverpool won their first ever FA Cup with Byrne again playing in every round. It was during the final against Leeds United when Gerry Byrne passed from ‘œPlayer’ to ‘Legend’ after playing for 117 minutes of the match with a broken collar bone.

In only the third minute of the contest, Byrne was involved in a collision with Leeds United’s Bobby Collins. Just moments before that collision, United’s Norman Hunter had injured his ankle in a tackle and so play was stopped so that both men could receive treatment. At first, it seemed as though it was Hunter who was more seriously injured, but as Byrne puts it himself,

“I went in for a tackle with Bobby Collins. He put his foot over the ball and turned his shoulder into me. I’d never broken a collarbone before, so I wasn’t aware of what damage had been done straight away. It didn’t cross my mind to leave the field and I played on with my arm dangling motionless by my side.”

In those days, there were no substitutions allowed, and so Liverpool played on with a badly injured player rather than be reduced to ten men. Trainer Bob Paisley did what he could to patch him up at half-time, but there’s only so much that bandages and aspirin can do. At the end of the ninety minutes, with no goals scored, the match went to extra time. At the end of extra time, Liverpool had won 2-1 with the first goal (by Roger Hunt) resulting from one of Byrne’s crosses. After the final whistle, more than two hours after the injury, Byrne walked up the Wembley steps to collect his medal, and then completed the lap of honour with the rest of the players. Somehow, the entire side as well as the coaching staff had managed to hide the severity of his injury from the Leeds players. It wasn’t until some time later that it was revealed that he had in fact broken the bone, and that he must have been in extreme pain the whole time. If Leeds had known, they would have exploited that weakness down Liverpool’s left flank and might have won. Shankly said afterwards,

‘Gerry’s collar bone was split and grinding together yet he played on in agony. It was a performance of raw courage from the boy.’

A few days later Gerry Byrne joined up with another previously injured player, Gordon Milne, to take part in one of the most famous laps of honour in Anfield history. The two of them came out with the FA Cup between them as Liverpool and Inter Milan warmed up before the first leg of their European Cup semi-final. The Italian players were frozen to the spot when they heard the roar from The Kop as the famous trophy was paraded before them. The Reds went on to win that match 3-1, but lost 3-0 in the second leg.

After a summer of rest, Gerry Byrne was fit, ready, and able, and played in every match of the 1965-66 season (plus 3 FA Cup and 9 Cup Winners Cup games), and picked up his second Championship medal in three years. By this time he had impressed England manager Alf Ramsey sufficiently to be made a part of the squad for the 1966 World Cup campaign, along with team-mates Roger Hunt and Ian Callaghan. It surprised quite a few at the time, as his only previous appearance internationally had been in a Home Championship loss to Scotland in the summer of 1963. Unfortunately, his only appearance for the squad was in a friendly against Norway, with England easily winning 6-1. Those two appearances were to be the only times that Byrne played for his country, as Everton‘s Ray Wilson was preferred by Ramsey.

Those were the glory days for Gerry Byrne, and sadly it was also the end of the major part of his career. In August of 1966, in the first match of the season against Leicester City, Byrne badly injured his knee and was never quite the same player again. Recurring problems with that injury led to his retirement from football in December of 1969, ten years (almost to the day) after Shankly’s arrival, and never having played for another club.

Bill Shankly was sometimes known for his overly enthusiastic descriptions of players, but it was no exaggeration when he described Gerry Byrne saying, ‘There isn’t a harder or “fairer” footballer in the game.’ Following the defeat of Belgian Champions Anderlecht in 1964, Shankly described Byrne’s performance as, ‘The best full-back display Europe has ever seen.’ There’s so much that could be said about Gerry Byrne and his contribution to Liverpool during those years, but again it’s probably best to quote Shankly, who knew him better that anyone,

‘When Gerry went, it took a big chunk out of Liverpool. Something special was missing.’

Liverpool supporters acknowledged Gerry Byrne’s importance to the club by voting him in at number 46 in the 100 Players Who Shook The Kop. There are also many who would say that Gerry ‘The Crunch’ Byrne shook plenty of opposition players as well.

Keith Perkins