As part of a series documenting the lesser-heralded names that helped shape Liverpool Football Club, Jeff Goulding tells the story of its early driving force, John McKenna.

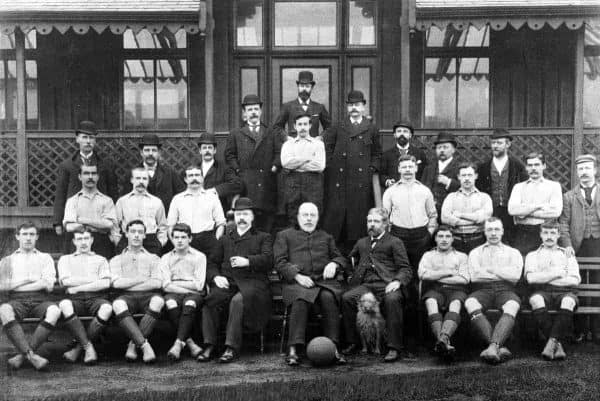

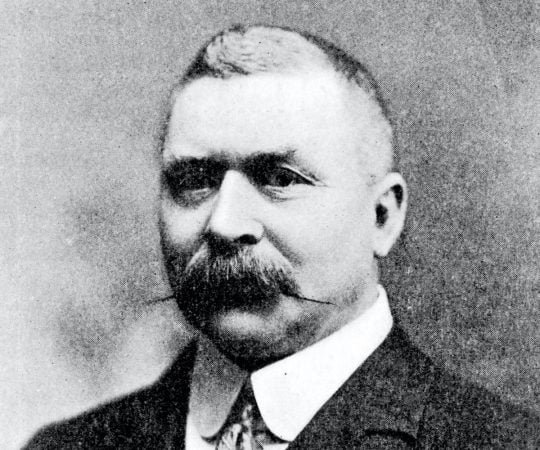

When he died, his coffin was carried through the streets of Liverpool by three players from Liverpool and three from Everton. He was described as “one of the most powerful and successful men at Liverpool Football Club—the third most important figure…after only Bill Shankly and the clubs founder John Houlding.” Alongside William Barclay, he was the club’s first manager. He would oversee the switch to red shirts—the Anfielders had originally played in blue and white. He also assisted with the recruitment of the eponymous ‘Team of Macs’. His name was of course ‘Honest’ John McKenna and this is his story.

It’s 1870 and in County Monaghan, Ireland, a young 15-year-old boy called Seán Mac Cionnaoith is boarding a ship to Liverpool in search of work. It is a journey taken by many men, women and children that century. But, while Seán’s ancestors had been fleeing starvation—the Great Famine had ended 18 years earlier in 1852—the man who would become known as John McKenna was taking this trip in order to better himself.

As he stood on the side of that vessel, staring out across the Irish sea, the wind in his face and his head full of dreams and schemes, he would have had little clue that he was about to play a pivotal role in the creation of a great global institution, hugely successful and beloved by millions. For this young Irish lad was destined to become one of the founding fathers of Merseyside football, and manager of Liverpool Football Club.

As his boat slowed and docked at the Pier Head, there would have been no Liverbirds to greet him, and no ‘Three Graces’ to herald his arrival on the Mersey. They wouldn’t arrive until the early years of the new century. Still the sights that greeted him that day would have been both awe-inspiring and terrible in equal measure.

Liverpool wasn’t even officially a city in 1870. It wouldn’t be granted that status until a decade later in 1880. It was a town that juxtaposed incredible wealth with staggering poverty. Its diseased streets, home to its citizens poor and working class, were crammed and uncomfortable places, ripe for frequent outbreaks of cholera. Meanwhile, its merchants and traders, who had benefited from trade in slaves, cotton, tobacco and other products, were living the high life. These industries would serve as a source of jobs and income for the local population as well as the tens of thousands of immigrants journeying to what many had called ‘the New York of Europe’ and the ‘second city of the Empire’.

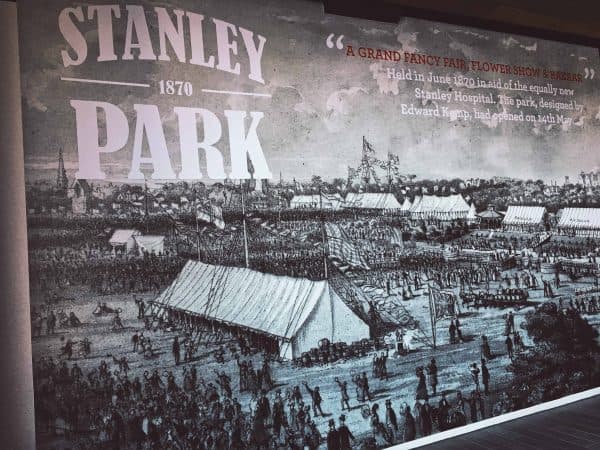

Though much smaller than today in terms of space, the town’s population was much larger than now. By the time McKenna arrived 600,000 people were crammed into the tight alleys and tenements. As as result, open spaces were at a premium. However, just 3.2 miles from the landing stage at the Pier Head, a new public park was about to open in the Walton area of the city. Stanley Park had been built to provide fresh air and recreational space to the populace of the suburb, who would have been members of Liverpool’s well-to-do elite at that time. And that piece of land was about to play a hugely significant role in young John’s future.

Liverpool today is a hotbed of football. It’s hard to find anyone who won’t engage in conversation about it, and who hasn’t developed strongly held allegiances for either the team dressed in red or the one sporting blue. However, in 1870, the beautiful game was in its infancy. The FA had been formed just seven years earlier in London, and like much of the country, Liverpudlians favoured rugby. John soon became an enthusiastic rugby player and helped form a regimental rugby club before joining the West Lancashire County Rugby Football Union as a professional.

Unable to earn a sufficient living from his sporting endeavours, John found work in the West Derby area of the city, as a vaccination officer. Somewhere around 1884, McKenna established a friendship with a man that would change not only his life, but the lives of countless generations to come. That man was John Houlding, a local brewer and soon to be Conservative mayor of Liverpool. It is not known how the pair met. Perhaps it was at one of the Masonic Lodge meetings that Houlding frequented. It is known that both men were Freemasons. Whatever the origin of their ‘meet cute’, they became strong enough friends for Houlding to invite McKenna to watch his football team, Everton, play a match at Anfield.

Everton had been formed as the city’s first professional club in 1878 and they played their matches on Stanley Park. However, in 1882 a new FA rule meant that they would be forced to play on a pitch surrounded by an enclosure. Houlding owned some land on Anfield Road and after a board meeting in the Sandon Hotel, which also belonged to him, Everton agreed to rent the land from him. They played their first game at the new ground in 1884, and beat Earlestown 5-0.

McKenna would soon become a fixture on the Everton board. He would assist with the expansion of the club, which was growing in size and stature rapidly. Attendances had risen to 8,000 and the team that then played in orange shirts with blue shorts and socks would clinch the First Division championship in 1891. By now the pair, along with William Edward Barclay, had forged strong bonds and close working relationships.

Then, at least as far as Everton Football Club were concerned, disaster struck. In 1892, a dispute over the rent paid on the Anfield enclosure led to a fracture in the board. George Mahon, a local liberal politician and methodist, led something of a revolt and Houlding was removed as club president. Everton would up sticks and set up operations at nearby Goodison Park. Houlding was left with a football ground, some old kits (blue-and-white shirts) and his two loyal mates, McKenna and Barclay.

The pair became joint-secretaries of the new club in 1892. It is said that Barclay took on the role of secretary-manager, while McKenna focused on team affairs and on-the-pitch matters. However it was John who telegraphed the FA, asking them to admit the club to the Football League; a request that was promptly turned down. That refusal would provide McKenna with an opportunity to cement his reputation as one of the finest administrators in the early history of the game. He would rise to the challenge and lead the club through the Lancashire League and eventually gained it promotion to the Second Division after a victorious ‘test match’ against a certain Newton Heath, who would later become Manchester United.

After winning the 1895/96 Second Division title, McKenna stepped back into the boardroom, but not before he switched the team from playing in blue and white to red shirts and black shorts. From that moment, Liverpool would be variously referred to as The Reds or The Anfielders. However, it was in his behind-the-scenes role that he made one of the club’s most astute and influential acquisitions—the signing of Tom Watson as first-team manager. Watson was a serial winner at Sunderland and would lead Liverpool to their first two top-tier titles in 1901 and 1906.

McKenna’s influence in the early years at Liverpool is difficult to overstate. His role was indeed pivotal and it’s not too great an exaggeration to say that the club we love today owes its birth and subsequent success in part to his excellent decision-making and stewardship. He would serve Liverpool as chairman twice, between 1909 and 1914 and again from 1917 to 1919. Though his time at Anfield would end as it started, with boardroom strife and acrimony.

In 1921, at a shareholders’ meeting, McKenna had wanted former player Matt McQueen and a fellow director, John Keating, re-elected to the board. However, when the voting was counted, two other men had been elected in their place. In protest, McKenna would immediately end his 30-year association with Liverpool Football Club. It was a desperately sad ending to his association with Anfield. By this time, John was already president of the Football League, a position he held from 1917 to the time of his death in 1936.

He would leave Liverpool in far better shape than when he found it, though. The club was now a well-oiled machine and primed to take the league by storm. The Reds would win back-to-back league titles in the 1921/22 and 1922/23 seasons. Interestingly, with Liverpool marching towards their fourth league championship in 1923, their manager, Dave Ashworth, suddenly and controversially resigned to take over at Oldham. The man who stepped into the breach was Matt McQueen, the former player whose ousting from the board had caused McKenna to resign in protest.

Paying tribute to the man he come to know as a friend, Everton‘s chairman, William Charles Cuff, had this to say:

“He will live long in the memory of all who had anything to do with the governing of football. Fearless, outspoken, and absolutely honest, he was well-named ‘Honest John’. The football world in general is under a very deep sorrow.”

John McKenna had set off from Ireland in 1870 as a mere boy in search of his fortune. He would leave the world as a formidable man. His contribution to football in general and Liverpool in particular was remarkable. When we think of the greats that litter this club’s history, it is perhaps sad that his name is so rarely mentioned. Of course, it absolutely should be, because without men like ‘Honest’ John McKenna, there simply would not be a Liverpool Football Club.

Fan Comments