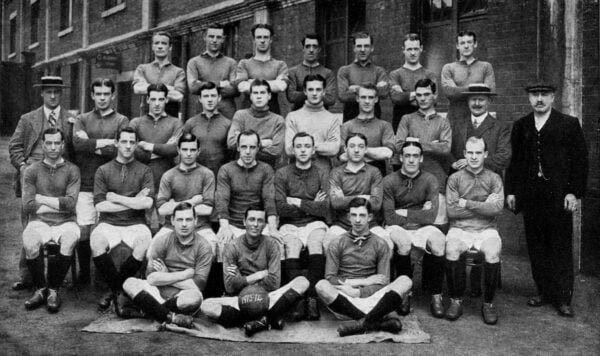

Tom Watson led Liverpool Football Club to its first two league titles, and its first-ever appearance in an FA Cup final. In an extract from a new book ahead of the 130th anniversary of his appointment, we look back at one Liverpool’s greatest managers.

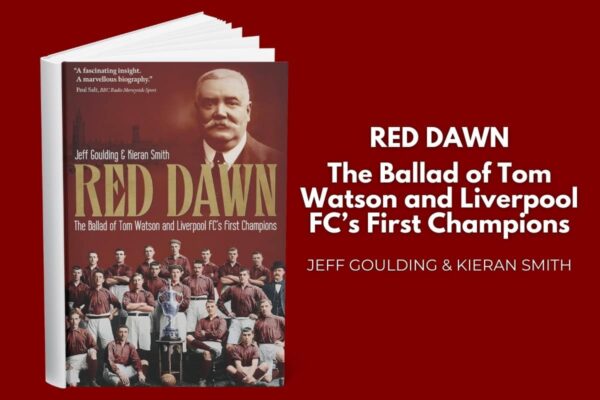

Unofficial club historians and lifelong Reds, Jeff Goulding and Kieran Smith have written an astonishingly detailed biography of Watson, the man who to this day is Liverpool FC’s longest-serving manager, and the heroes he led to glory.

Here, This Is Anfield publishes an exclusive extract, which details how Watson shocked the sporting press by eliminating Aston Villa at the FA Cup semi-final stage, securing Liverpool’s first appearance in the final at Crystal Palace in 1914:

Extract from ‘Red Dawn: The Ballad of Tom Watson and Liverpool FC’s First Champions‘, written by Jeff Goulding and Kieran Smith.

The press had Liverpool as clear outsiders to reach the final. Villa were the form side, and many felt they would stroll through the tie. This was something that clearly riled Tom Watson. Before the game, he assembled his players in a hotel for lunch and, as they finished, he rose to his feet to deliver one of the greatest battle-cries the team had ever heard.

Reds former goalkeeper, Ken Campbell recalled the events later in an article for the Weekly News, in 1921.

In it he describes Watson’s harsh words for the gentleman of Fleet Street, and by all accounts “Owd Tom” had turned red in the face, such was his anger.

As he finished his speech, Campbell recalls that he thumped the table, causing crockery to jump all over the place, before declaring: ‘Never mind boys, I want you to turn out today and show them up. Show them there are more players than Aston Villa in the semi-final.’

His words seemed to have the desired effect and the Reds ran out 2-0 winners. For the first time in their history, they had reached the final of the FA Cup. Some described Liverpool’s run to the final as lucky, a claim that angered Watson and players like Ephraim Longworth, who told the Sport Angus, on September 12th, 1914:

‘It was against Aston Villa, however, that we recorded our greatest triumph – that we won against the greatest odds. There is no need for me to recall the details; they will be well remembered. The amazing form of the Aston Villa side for the few months previous was discussed on every hand. They were the favourites. It was merely a question of how many goals we should lose by. The odds were against us, but we won against the odds. How did we do it?

‘In the first place, the side who hope to win against odds must be fit as fiddles – every man trained up to a nicety to last the whole of the game, and every man ready and willing to put forth that bit of extra effort necessary if a better team is to be beaten. And it is no good trying to win against odds if your men go on the field with the fear of defeat in their hearts.’

Liverpool would contest the FA Cup final on April 24th, 1914. Their achievement in reaching the final electrified the city, placing them within touching distance of elite status in English football.

Were they to win it, it would exorcise Watson’s ghosts, after he come so close on six previous occasions, three of them with Sunderland, only to see his teams go out in the semi-final stage.

We now know what an emotional character Watson was, and can speculate on the turmoil of hope, expectation and anxiety that must have gripped him in the run up to the Final. For the club’s supporters, however, there seems to have been excitement and joy bordering on delirium as they prepared to make their way to the capital.

Sadly, Liverpool would lose the game 1-0, but events that took place a mere 48 hours before saw the players earn the wrath of their manager and may have affected morale in the camp.

The players and club management had been staying in the Forest Hotel in Epping, London. In the early hours of the morning, a couple of days from the final, team trainer Bill Connell was awoken from his sleep by a loud noise coming from the billiard room below. The paper picks up the story:

‘Down in the Forest (Epping) something stirred, and it wasn’t the note of a bird, but of several players returning, via a window in the billiard room, in the small hours of the morning.

‘They were not given railway tickets and sent home, like Chelsea. They were not even admonished as the re-entered the hotel after their midnight marauding. They were allowed to sleep in peace.’

However, if the players thought they had gotten away with their nocturnal adventures, they would be in for a rude awakening. Manager Tom Watson would serve up the sternest of rebukes for breakfast, leaving none of them in any doubt of how he felt about matters.

This meant so much to Tom, and the thought that his players were giving the occasion anything less than their utmost concentration had infuriated him.

‘[…] Manager Tom Watson, one of the greatest the club ever had,’ the Echo continues, ‘tore such a large strip off them they would far rather be sent Anfieldwards to escape such a verbal lashing.’

Secrecy around the events was maintained for five decades, and supporters who attended the match never heard of what happened before the game. The behaviour of the players was certainly not unusual for the time, and purveyors of the modern game will have similar stories to tell but is interesting – if perhaps unsurprising – to note that managers and trainers as far back as 1914 understood the value of discipline and focus as much as their latter-day counterparts, and it is a testament to their professionalism.

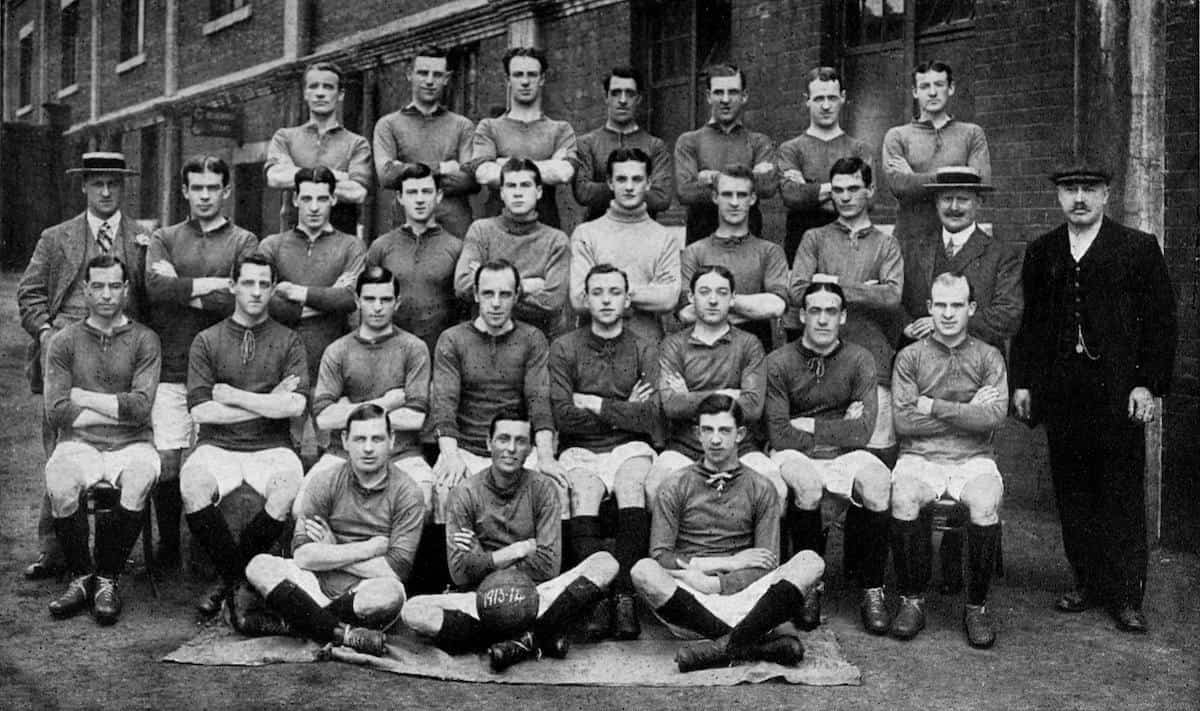

To add injury to insult, Liverpool’s captain, Harry Lowe would suffer a setback that would ultimately keep him out of the game. He would be replaced by 23-year-old Donald MacKinlay. He along with Ephraim Longworth, and Bill Lacey would feature in the game, and also went on to be part of the famous team of ‘Untouchables’ who won back-to-back league titles in the 1920s.

On the day of the final, the weather was described as sunny but overcast. Burnley, who had trained in Lytham, and travelled to London the evening before, staying in a nearby hotel. Of course, we know Liverpool had boarded at the Forest Hotel in Epping.

It had been decided that Tom Watson and his coaching staff, would travel to the ground in taxis, with supporters and friends waving them off.

The players would be presented to the King, who had granted a personal audience to the captains of each side. He also posed for a photograph with them, as did the Duke of Lancaster who, it was noted, was wearing a red rose on his coat.

Liverpool goalkeeper recalled the day seven years later, in an article entitled, ‘My Five Minutes With The King,’ published June 18th, 1921. Campbell explains how the team had been aware of the challenge that lay ahead of them, but they were nonetheless confident that they would ‘take a lot of beating.’ He would also recall how the loss of captain, Harry Lowe would prove extremely costly:

‘[…] our hopes got a wee bit shattered by an unfortunate incident, and I do not hesitate to say that it had a deal to do with what happened to us at the Palace.

‘We played Middlesbrough in a League match the week previous to the final, and owing to our having a somewhat weak team out – Lacey, Sheldon, Longworth, and myself of the cup-tie team were not playing – we went down 4-0.

‘That in itself would have been a bit of a shock, but what really did tell was a regrettable accident to Harry Lowe, our centre-half, who had his knee injured in this game. Once more the uncertainties of football demonstrated.

‘Never shall I forget the anxiety of the following week. We went down to Chingford again for special training on the Monday after the Middlesbrough match.

‘Would Harry be fit? That was the question of the hour. You know how little things like that upset one, and we were strung up to the highest pitch.

‘Harry was sent to a specialist in London, and he gave great hopes of being able to play. Our spirits rose again. We trained hard and earnestly, and felt that, after all, things were not to be so bad. Harry attended the specialist every day, and on the Saturday he went to have his knee strapped up.

‘He came back to Chingford about lunchtime, and we all went on to the green in front of the hotel to see him try his leg.

‘I remember it all so well. Little Jacky Sheldon threw the ball to Harry’s bad leg, and called – “Kick it back to me, Harry.” Poor Harry made an attempt, and then drew back !! “It’s no use, boys,” he said, and the tears were in his eyes. And I am not ashamed to say that most of the boys felt like that.’

It is clear to us that, after reading Ken Campbell’s words, how much of psychological impact the loss of Lowe had on the rest of the team. It also speaks to the togetherness amongst the lads, and sense of family. However, it would mean that as least in their heads, they felt that they were at a disadvantage before they had even kicked a ball, and such things can prove pivotal as much then as they do now.

Did the Liverpool players believe they were already beaten? Consider these words from Campbell:

‘The tragedy of it! To be robbed of the services of our pivot on the eye of such an important event – one on which we had set our hearts so much – was a real tragedy to us.”

There would be further anxiety when the players arrived at Crystal Palace. Of the five taxis that took the men to the stadium, only four had actually arrived. The players joked amongst themselves that they had been kidnapped, but Tom Watson was beside himself with worry.

In desperation, at 3 o’clock, the manager went to the entrance gates to see if his men had arrived. In just 20 minutes they were meant to be in their kits and presented to the King.

To his enormous relief, he found them, struggling to make their way into the ground past a huge crowd. They had been trying to get past the commissionaire for quite a long time, but that official was adamant that all the players had already gone in. The poor man was used to chancers turning up at his entrance, and pretending to be players.

Watson, though relieved, was exasperated by all of this, and is said to have torn a strip off the poor commissioner. Nevertheless, he would need the assistance of Mr F. J. Wall, the English Football Association secretary to persuade the man to allow the players to enter the stadium.

To say that Tom and his men were ill-prepared for the final, seems something of an understatement. Ill-discipline, an injured captain, and distracted by pre-match drama, it really couldn’t have been any worse.

The only silver lining for the players was the late arrival of the King, which meant they would all be ready for inspection before kick-off.

Despite the prematch chaos. Watson’s men gave a good account of themselves in the final, but hearts would be broken as the Reds succumbed to a 1-0 defeat.

It would prove to be Watson’s final moment in football’s spotlight. In 1915 the football world was rocked when “Owd Tom” – who was still making plans for the Reds’ next campaign – passed away after a short battle with pneumonia. He had, however, laid the foundations for Liverpool’s all-conquering team of the 1920s.

Thanks to Tom, others would go on to reap the fruits of his labours. The club is what it is today because of men like him.

The above is an extract from ‘Red Dawn: The Ballad of Tom Watson and Liverpool FC’s First Champions‘, written by Jeff Goulding and Kieran Smith. It is available in hardback and ebook here.

Fan Comments