In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic and the suspension of football, UEFA are expected to relax their rules over Financial Fair Play, which could affect Liverpool.

In those innocent times when complaints about VAR outnumbered mentions of furloughing, Liverpool represented a footballing and financial success story.

They had made back-to-back big profits—a record-breaking £125 million one year, a pleasing £42 million the next—while reaching consecutive Champions League finals.

They had established the Premier League’s biggest lead while outperforming the clubs with the deepest pockets. For all the talk of Financial Fair Play, this was financial good play.

As in many other respects, coronavirus proved a game-changer. Liverpool’s misguided, and ultimately reversed, decision to furlough non-playing staff highlighted the reality that even the best-run clubs have concerns about costs during an extended period without football.

Rainy-day funds can be drained by what is a deluge. Even the most prudent fear going underwater.

The sad reality for Liverpool is that the simplest way to inject money into a sport that will be drained of it by a lack of matchday income—potentially for a long time—and broadcast revenue—should seasons not be completed—flies in the face of their beliefs.

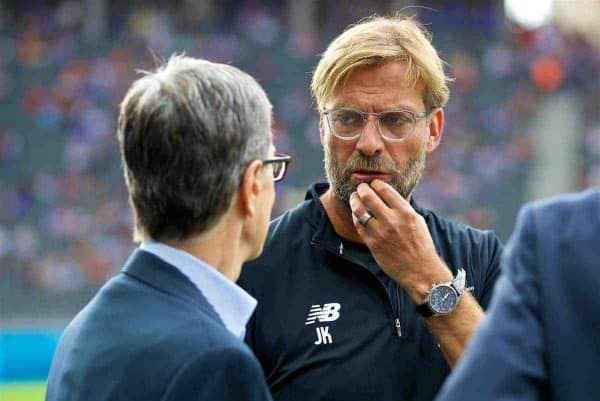

Liverpool have been strong supporters of Financial Fair Play, and not just because even men as wealthy as John W. Henry and Tom Werner do not boast the resources of Roman Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour or the willingness to fund a club themselves.

They have prospered within its parameters, based on four factors. Most obviously, on-field success, with the prize, broadcast and matchday revenue that generates. There has also been the commercial acumen to transform their sponsorship and marketing deals.

They have been excellent sellers, commanding the second-highest fee ever for Philippe Coutinho and premium prices, given their respective abilities and attributes, for Christian Benteke, Jordon Ibe, Dominic Solanke and a host of others.

They have arguably been even better buyers, with bargains including Sadio Mane and Mohamed Salah and the rather cheaper Andy Robertson and Joe Gomez, and a very high strike rate.

But all calculations are made within certain expectations; they include football matches happening with crowds and, indeed, happening at all, which were conditions under which all contracts were agreed.

UEFA is set to relax Financial Fair Play guidelines; it has to, otherwise a host of clubs will fail them. There is a case for waiving them altogether for a year or two.

That case may stem more from pragmatism than morality, but it is one of the few ways to get extra money into the game at a point when plenty is coming out (and that is even before considering the pool of commercial partners feels altogether smaller, and thus many deals lower, when some industries will be in no position to advertise).

Some of clubs’ expenditure—wages from contracts agreed in the past—remains while their income is reduced.

In short, that artificial injection of funds could come from the super-rich, from those less concerned with getting value for money or turning in a profit. Around half the money Premier League clubs spent in the depressed market of the summer of 2003 was paid by Chelsea, flush with Abramovich’s millions.

Now there would be four obvious beneficiaries of an ability to spend unlimited funds without sanction: Chelsea, should Abramovich show such intent again; City, who may need something of an overhaul and who have been found guilty of breaching FFP; Everton, given Farhad Moshiri’s ever-present willingness to buy; and Newcastle, assuming their takeover goes ahead.

The competitive advantage Liverpool got from coaching, cohesion and chemistry could be cancelled out in one splurge, years of fine decision-making rendered less important than the size of an owner’s bank balance.

Because there is a difference between billionaire owners—a category that includes FSG, Arsenal’s Stan Kroenke and Tottenham’s Joe Lewis—and those who are even wealthier.

A summer of unlimited spending would benefit Chelsea and City. Man United, with their huge commercial revenues, are reasonably well positioned, though Ed Woodward has said it is unlikely to be “business as usual” for them this summer.

The same may apply to Liverpool, but not spending last summer could benefit them if prices come down; anyone with cash in the bank can exploit the vulnerabilities of others.

Arsenal and Tottenham, unlikely to qualify for the Champions League—one having made a loss last summer, the other potentially with a £1 billion stadium standing empty for some time—would be at the greatest competitive disadvantage.

But in Liverpool’s case, the most pertinent comparison is with City; it would hand Liverpool’s immediate rivals an immediate boost.

Money talks, and Liverpool would have less equity in their squad with transfer prices certain to come down. In one respect, that matters little: none of the starting XI were expected to be sold anyway.

But the plan may have been to boost the transfer kitty with the proceeds of possible departures like Divock Origi, Dejan Lovren, Loris Karius, Xherdan Shaqiri and Harry Wilson who, a couple of months ago, felt worth at least £15 million and potentially £20 million.

Allowing City or Chelsea to spend £200 or £300 million might scarcely alter that. Yet it would get some money flowing around what could be a static market again. It might be welcomed by some smaller clubs who fear their assets otherwise become worthless.

It is worth noting that trickle-down economics rarely work the way right-wing politicians think they do; if City spend £100 million on a footballer, it certainly does not follow that, somewhere further down football’s food chain, someone will pay £1 million for a Tranmere or Accrington player.

If the initial transfer is with a foreign club, the English game may never see the cash again. And yet some added investment would at least help some clubs in troubled times.

And so, at a point when all sports are facing their greatest economic crisis for decades, waiving FFP rules for a summer could be both the right thing for football, and the wrong thing for Liverpool.

Fan Comments