Jeff Goulding takes a look back to Liverpool FC’s storied past, with Tom Watson leading the Reds to victory over Manchester United in 1911

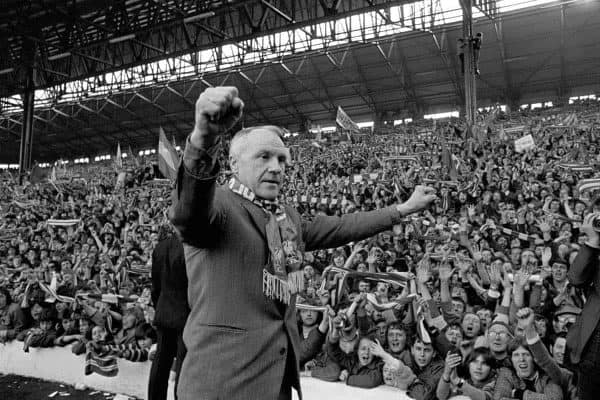

When Kopites are asked to list the club’s greatest managers, the names Shankly, Paisley, Fagan, Dalglish, Houllier and Benitez roll easily off the tongue. Most of us struggle to choose between Bill and Bob in attempting to name the greatest of them all—Bob was the most successful, but it was Shanks who got it all started. Wasn’t it?

In writing these classic game pieces, I have come to realise just how rich our club’s history is. We often criticise Sky Sports for creating the illusion that football was invented in the 1990s. However, I can now see that many of us, myself included, are guilty of believing the Liverpool FC only really found greatness in the 1960s. It’s an idea that does an incredible disservice to so many heroes of a bygone age.

I believe their stories deserve to be told. So, for this classic match feature I want to celebrate one of Liverpool’s true greats; a manager whose name should echo in eternity. Tom Watson, born in Newcastle, joined the Reds in 1896 from Sunderland. There he had won three First Division titles, crowning his success with a World Championship in 1895.

He would go on to manage Liverpool FC until his death in 1915, racking up 742 games. History shows it was Watson who started the club on its long road to success, winning the club’s first two titles in 1901 and 1906, becoming the first manager ever to win the league with two different clubs. He would add the Sheriff of London Charity Shield in 1907.

Under his guidance the Reds would also finish runners up in the First Division twice, win the Second Division title and take the club to their first ever FA Cup final in 1914. Sadly they lost 1-0 and Tom died a year later.

Watson was famous for his ability to organise his teams and for his fierce team talks. In dressing room, during the 1914 FA Cup semi-final against Aston Villa, he was so incensed by the London Press’ treatment of his players that he raged:

“Never mind boys. I want you to turn out today and show them up. Show them there are more players than Aston Villa in the semi-final.”

So respected in the game was Watson that few players could turn him down when he came calling. Writing in the Liverpool Echo in 1924, Victor Hall had this to say:

“One of the secrets of his success in discovering new players was his own personal popularity. Everyone he met liked him and was always ready to do him a service.”

Like the great Bill Shankly, Tom also believed that diet and exercise were the key to success for his players. However, his prescription of chops and eggs on toast for breakfast and wine for lunch would raise a few eyebrows today—he did tell them to use tobacco sparingly though.

Meanwhile, his technique for keeping the players warm during the winter games involved rubbing neat whiskey on their chests and backs. Team bonding consisted of long walks with the players and coaching staff.

Such was Watson’s stature in the city, and in the world of sport generally, that he was awarded what was almost a state funeral when he died in 1915. Anfield cemetery was said to be awash with floral tributes numbering more than 100. Wreathes were laid by Liverpool and Everton and all the major football associations.

People from civil and political life turned out also; proving that Tom Watson was a giant of the game and just as much a hero to Liverpool supporters as any of our modern greats.

So, as we prepare to battle with Jose Mourinho’s United in 2016, I want to take you back to one of Watson’s epic victories against our old enemy, at Anfield, in 1911. The Liverpool that Tom Watson lived in was a culturally diverse melting pot, with almost 800,000 people crammed into just 40 square miles. Irish, Welsh and Scots mixed with Africans, Chinese, Indians and Greeks amongst many more.

Liverpool had only achieved city status three decades earlier, in 1880, but it was now regarded as Britain’s second city. In 1886, the Illustrated London News had this to say:

“Liverpool…has become a wonder of the world. It is the New York of Europe, a world city rather than merely British provincial.”

1911 saw a new monarch, George V, ascend to the throne, and in Liverpool the Liver Buildings were rising into the sky. Construction of the city’s ‘skyscraper’ had started three years earlier and now all that was left was for the clocks to be synchronised with the exact moment of the coronation.

Juxtaposed with royal and architectural grandeur was a country on the brink of revolution. Strikes, riots and uprisings took place in all four corners of the British Isles and Liverpool was no different. A general transport strike had brought the city to a standstill and saw the government put troops on the streets and tanks on St George’s Plateau. The warship, HMS Antrim, was anchored in the Mersey; its guns were trained on the city centre.

Riots broke out on Lime Street, in August, as a huge demonstration was charged by police and soldiers. Sadly two striking dock workers were shot dead. On the plateau that day was one Bessie Braddock, aged 12, with her mother. She would go on to represent the city in parliament. Today you can find her statue locked in an eternal encounter with Ken Dodd’s, on the concourse at Lime St. Station.

On November 18, United came to Anfield. The Kop was barely five years old and Irving Berlin, not Gerry Marsden, was tearing up the charts. Liverpool wore red shirts, with white shorts and red socks. They had adopted the Liver Bird as their official emblem in 1901, but wouldn’t wear it on their shirts until 1947. United, the champions, would wear their blue-and-white-striped away shirt.

The game kicked off at 14.45pm, in front of a capacity 15,000 crowd. Liverpool’s captain that day was Arthur Goddard—he had signed in 1902 from Glossop for £460, a record fee at the time. The Liverpool Echo described him as “a well-preserved, gentlemanly player, with a graceful style.”

Both teams were struggling in the league at this point. United were 13th and the Reds were 17th, and it showed. The first half was a tense affair. With Liverpool flirting with relegation, they desperately needed the two points on offer. The crowd grew tense as the players struggled and failed to break through the United defence. They would leave the pitch at half-time, goalless.

The second half, though, was a different story and the game seemed to explode into life. In the 57th minute, Enoch West broke Kopite hearts, putting the Mancs 1-0 up. He’d proven to be a thorn in Liverpool’s side, scoring eight goals in 15 games against the Reds.

Things seemed grim, but Liverpool rallied and struck back against a United team who didn’t seem to know what had hit them. Twenty-six-year-old Bootle-born Scouser, Jack Parkinson, levelled just two minutes later. Parkinson was a pacy wide player with an eye for goal. He debuted in 1903, scoring six goals in 17 games, but the following season managed 20 goals in 21 games.

Sadly Jack’s career was dogged with injury, nevertheless he maintained an incredible goals-to-games ratio of 1.71. His best season came in 1909/10, when he finished top scorer with 30 goals; netting 11 goals in his first seven games. Jack Parkinson: another forgotten legend.

Back to the game and Liverpool went 3-1 up in a breathtaking three-minute spell that sent Anfield wild. John Bovill, a Scot, took the plaudits, scoring a magnificent brace. He’d only signed for the Reds in the April of that year. He made 29 starts, most of them coming in the 1911/12 season. He’d go on to score seven goals that year. Sadly this would be the high point.

While regarded as a workhorse with an eye for a pass, his “lack of deadliness in front of goal” would prove his undoing. Still he scored two against the Mancs, that’ll do for me, John.

With Liverpool seemingly cruising at 3-1, the much-needed points appeared secure. United, though had other ideas and, in the 88th minute, Charlie Roberts ensured a nervy finish for Kopites, with what proved to be a consolation strike.

Blackburn Rovers would go on to win the league that year, with our neighbours from across the park finishing second. United would finish in 13th and the Reds would avoid relegation, limping home in 17th spot. These were very different times, though, and Watson’s position as manager was never in doubt.

He would remain in the hot-seat until his dying day, in 1915. His last success was a league title in 1906 and his side had failed to bring home the FA Cup in 1914.

Nevertheless, he left this life as a Liverpool legend, held in the highest esteem by all Reds and the wider sporting community.

Though his tenure lies beyond living memory, his story deserves to be told and his legend demands to be celebrated. Tom Watson, Liverpool manager.

It all started with you and your boys, Tom. Thank you, and rest in peace Redmen.

Fan Comments