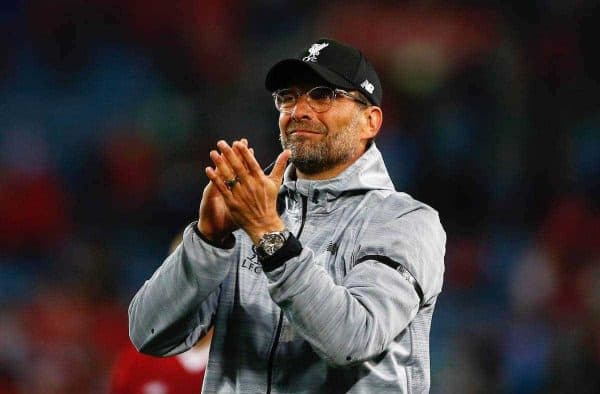

Liverpool’s woes this season are well-documented but Jurgen Klopp says he is normally a good defensive coach. Does his past point to a better future?

Whether the blame is given to the tactics and system or coaching and playing personnel, the end result is the same: the Reds simply haven’t defended well once again this season.

There has been an element of ill-fortune involved at times, as discussed here, and it’s worth remembering that at the back end of last season, Liverpool’s defensive resilience was a big part of sealing a top-four finish.

But it hasn’t lasted, and in 2017/18 only two clubs have conceded more goals in the Premier League: West Ham United and bottom club Crystal Palace.

“It’s obvious we concede too many, there’s no doubt,” Klopp said after the recent league win at Leicester.

“That’s really hard for me. Usually, I’m a really good defensive coach, but obviously that has worked not too well so far.”

It’s a statement that he expects more from his players and perhaps from himself—but does his record back up his words?

And if so, is an improved defensive record a factor which Klopp quickly built into his previous sides, or was it the result of a more sustained, long-term approach?

Team by team

Naturally, there is a big discrepancy between Klopp’s defensive records at each of his clubs.

They cannot be directly compared with each other: one was a team he achieved promotion with, whereupon they were a small club in a big league; one was a giant and now one is in a different country with more league matches per season.

Still, there are stand-out points to note from the pure data.

Only three times have any of Klopp’s sides gone through an entire league campaign achieving a season-long goals conceded average of 1.0 per game or less.

Those three seasons resulted in promotion (with Mainz, 03/04) or winning the title (Dortmund, 10/11 and 11/12).

A strong defence, reliable and resilient for an entire year, yields rewards. This isn’t new information, but it is apparently a link which some still fail to grasp.

Klopp’s average goals conceded per game (top flight only) reads as follows:

Mainz: 1.6 (102 games, three full seasons)

Dortmund: 1.04 (238 games, seven full seasons)

Liverpool: 1.25 (75 games, one full season, two part-seasons)

A year ago, we took a tremendously in-depth look at how Liverpool’s defensive record was shaping up under Klopp.

Key points to note:

• Brendan Rodgers’ Liverpool side conceded 82 in his last 69 games, all competitions, or 1.19 per game (start of 14/15 up until his dismissal)

• In Klopp’s first 61 in charge of Liverpool, all competitions, the Reds conceded 68, or 1.11 per game.

• The average goals conceded per game across five years by the fourth-placed team was 1.04

• The average across the same time frame by the title winners was 0.93

• Liverpool’s average over that span, 11/12 to 15/16, was 1.22

Thus, Klopp’s defensive record in league games at Liverpool has actually seen the team get marginally worse than during that five-year period before he joined, up to 1.25 conceded per game.

Trends and insight

It’s disappointing that the Reds appear to be making no headway in improving at the back, but after the summer transfer window it can’t be a surprise.

The Reds didn’t make any kind of addition or improvement to anywhere in the defensive spine of the team, and didn’t change tactics. Improvements rarely happen magically in football without one of those two factors being altered.

So what about Klopp’s building, his progress over time?

The below charts show his team’s defensive record changes year on year. Note the first graphic, Mainz, has three years in the top flight included when the goals conceded average spikes naturally.

It’s difficult to make any immediate claim or assumption that given time—and for a modern manager, seven years is an extended amount of time—Klopp naturally improves his team’s capacity to avoid conceding goals.

At Mainz he steadily improved the side of course, and BVB improved to win the title, but either side of those two successful years, his last three seasons at the Westfalenstadion were roughly the same as his first two.

And at Liverpool there’s no real pattern whatsoever: an overall improvement last term, but worse than ever this year so far—over a much smaller pool of games, though.

On the other hand, there’s a lot to be said for consistency, which is largely what Klopp has achieved throughout.

There is only so much that teams can improve in any regard, and when one part of the team is altered—a more dynamic attacker for example in place of a functional midfielder—the balance is naturally upset somewhat.

Opt for more offensive prowess, and a natural and near-unavoidable consequence is less defensive stability. The never-ending battle is tough to get right.

Therefore it should be accepted that at the elite level, maintaining a good defensive record is almost as laudable as fashioning a defensively resilient team.

Fine margins might dictate whether that leads to silverware, but keeping tight at the back increases chances of that happening.

Two details worth accounting for from the above data: 15/16’s record of 1.32 conceded per game takes in the whole season, including the eight games Rodgers was in charge for. Klopp’s own record was 40 conceded in 30—or 1.33, so very slightly worse.

And, while 16/17 was Liverpool’s best defensive record since 11/12, much of that was due to five clean sheets in the last six games of the campaign.

Up until that point, the Reds had conceded at a rate of 1.25 per game across 32 fixtures, much more in line with the previous three seasons—and equal to Klopp’s overall league record with the Reds.

The frustration for many supporters will be in seeing that the team is capable of shutting down the opposition over a run of games when it really mattered—but not, apparently, over a sustained period.

Forward and future

Klopp is a big believer of improving players by coaching, as indeed Rodgers was before him.

But coaches aren’t magicians, nor can they bully, cajole or reassure players enough to be better than their own natural ceiling.

Liverpool have had for some years, and still have now, players in certain defensive roles who are not elite, who cannot reach elite status.

And while Klopp is right to suggest he is usually good as a defensive coach—eight of his 15 seasons before moving to Anfield yielded a better goals conceded rate than Liverpool’s five-year average pre-Klopp—he perhaps hasn’t got the track record to suggest that he makes vast improvements by tutelage alone.

Buying players is key, as it ever has been.

Few fans want Liverpool to just spend tens of millions for the sake of it, but this is far from that—it’s a problematic area of the team which hasn’t been able to be fixed by time and coaching alone, thus needs an alternative approach.

Better natural defensive acumen, better organisational characteristics, better understanding of the style Liverpool play, in possession and high upfield in attacking moments: all these traits are desired in new additions.

With better-suited individuals, then Klopp’s methods should be able to translate more effectively—and yield the results he wants, the results he believes his coaching can deliver.

As an aside to spending, for example, £60 million on a certain Dutch centre-back, Klopp’s ability to maintain a sustainable good defensive record should be great news for youth prospects, who get to learn and play his way from early on.

Joe Gomez and Trent Alexander-Arnold should, along with Klopp’s penchant for trusting youngsters as he has, benefit from having the manager’s methods ingrained in them.

If and when better mentors arrive for them to perform beside, then there should be a positive outlook for the mid- and longer-term development of the defence.

Until then, Klopp’s career history doesn’t necessarily indicate that he’ll improve those already in place to such an extent that a title challenge is heading Liverpool’s way, regardless of how well the attack functions.

Fan Comments