As part of his series of The Men Who Made Liverpool, Jeff Goulding recalls the brilliance and late tragedy of one of the club’s founding fathers, William Edward Barclay.

A paragraph, printed in the Liverpool Echo on January 31, 1917, reports the “suicide during temporary insanity” of a 60-year-old munitions store keeper who resided in Upper Beau Street. He had injuries to his forearm, there was a razor next to him and a note, addressed to a friend, spoke of his intention to end his life.

The man in question was William Edward Morton Barclay, and the newspaper suggested he “had once been in a better position.” This was perhaps a case of monumental understatement, for Mr. Barclay had once been club secretary at Everton and later became the first man to manage Liverpool Football Club. This is his story.

Barclay was born into a middle-class family in Dublin, in 1857. His father, David, was the governor of the Malone Reformatory; an institution that provided an alternative to prison to young offenders, a position that would have ensured the family were comfortably off. William took full advantage of his good start in life, achieving two university degrees—a Bachelor of Arts and Science—and his addresses show that he travelled extensively during his young life.

The man who would play such a pivotal role in Merseyside football would make homes in Belfast, Aberdeen, Lancashire—where he married in 1878—and eventually in Liverpool. It was around the time of William’s marriage to Emily King, a Yorkshire woman, that St Domingo FC were formed, in a suburb of Liverpool called Everton. The team had been put together by the Methodist clergy to allow the residents of the parish an opportunity to play sports all year round, with cricket being a summer game. Association football was in its infancy and their games were played on Stanley Park.

By now Barclay was following in his father’s footsteps, and was employed as the governor of an industrial school in Everton, a position he held until 1898. His work would see him providing education, board and lodgings to poor and neglected children of the borough. William was now established in the city and clearly a man of means, and this would have placed him in the same circle as other influential men, like John Houlding.

Houlding, of course, was a key player in the development of St Domingo FC into Everton Football Club and its move from Stanley Park to Anfield. It is clear that both these men became good friends, along with John McKenna, and also key allies in the Everton board.

So much so, in fact, that William Edward Barclay would become the first secretary/manager of the club during the inaugural 1888/89 Football League season.

This was the Victorian era, a period in which Jack the Ripper carried out his dastardly acts in Whitechapel and the city of Liverpool was growing in stature and economic power.

The First Division consisted of 12 teams and none of them were in the south of England. Everton, who played in blue-and-white striped shirts, finished in eighth place. They had amassed 20 points, winning nine, drawing two and losing 11 games. Their problems clearly lay in defence, as they had shipped 47 goals. The footballing benchmark of the era were Preston North End, who completed a historic league and FA Cup double.

Perhaps wisely, Barclay stepped back into the boardroom, where he would put his skills in administration to much better use. The team would improve the following season, with a highly creditable second-placed finish, and they would go on to be champions in 1891. However, tensions in the boardroom were growing. Perhaps motivated by religious or political differences, a split was forming between the Methodist and liberal wing and a group allied to local brewer and Tory politician, John Houlding, who was also a member of the Orange Order.

It is now well known that a dispute ostensibly over the rent the Everton board paid to Houlding for the land he owned on Anfield Road led to the formation of Liverpool Football Club in 1892. However, it is likely that rivalries based on cultural and political alliances played a part too. It is known that some members of the board disapproved of the players drinking in the Sandon Hotel, also owned by Houlding. Some even blamed Everton‘s failure to retain the title in 1892 on this fact. The team had slumped to fifth place and the club was beginning to fall apart.

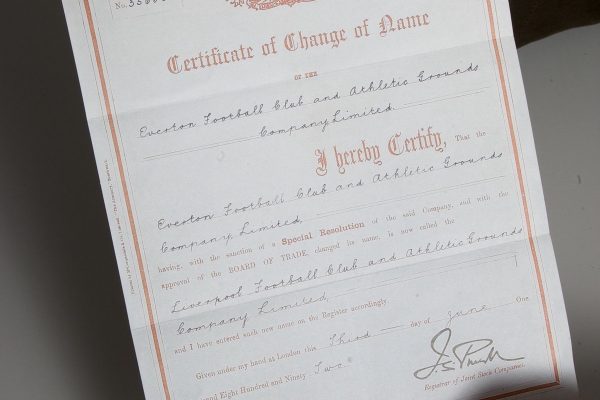

The inevitable fracture occurred during a meeting of 500 club members, in which Houlding had received just 18 votes in what was essentially a vote of no confidence, and was removed as club president. Barclay would be one of the men who remained with him at Anfield, and it was he who came up with the idea to call Houlding’s new venture Liverpool.

The new team would first have to first ply its trade in the Lancashire League, after an application to join the First Division was rejected. It is suggested that the board of the newly formed club blundered in not simultaneously applying to join the Second Division, an error often laid at the door of Barclay’s colleague, John McKenna.

However, a letter written by Barclay to Field Sport in June 1892, and describing himself as honorary secretary of the Liverpool Association Football Club, tells a different story and was Barclay’s way of announcing the club to the football world:

“Sir, […] we have joined the Lancashire League, and have thus provided a very interesting series of fixtures for our first team. We regret that we could not see our way to make application to enter the Second Division of the league, as we felt, after very careful deliberation, that the gates would be no better than the gates drawn with Lancashire clubs, whilst the traveling expenses would have been very high.”

Whether this was merely a party line, masking an error on the part of McKenna, we will never know. However, it is clear from the following passage that the newly formed board of Liverpool AFC meant business, and had lofty aspirations for the future:

“We hope to meet some of the league clubs during the season, and already engagements have been made with some of the leading Scottish clubs for odd dates. Cup ties—English, Lancashire and Liverpool—will fill vacant spots, and altogether I think the ‘bill of fare’ at Anfield will not disgrace the past.”

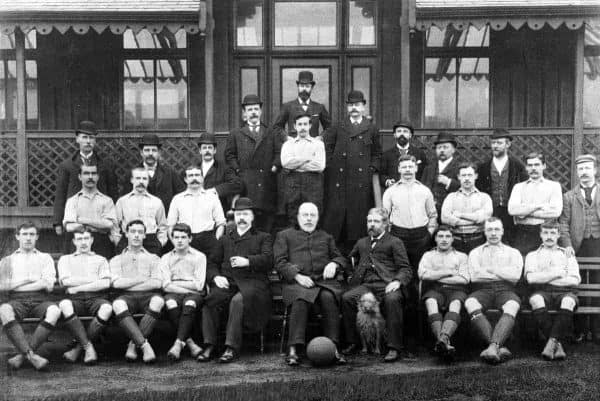

Working alongside McKenna, who is credited as having recruited the ‘Team of Macs’—players drafted from Scottish football—Barclay as honorary secretary would have at least approved the signings of these men. In his letter to Field Sport, he boasts:

“As to players, the following have signed: Andrew Hannah, Renton, back; Sydney Ross, goal, Scottish League vs. Scottish Alliance; half-backs James Kelso, John Cameron and James McBride (Renton), and F. Rogers (Liverpool); forwards, Jock Smith (Sunderland), Thomas Wyllie (Everton), John Miller (Dumbarton), Andrew Kelvin (Kilmarnock), and one or two men of less repute. In addition we shall have at least four of the best players in Scotland, with whom we are now negotiating. Our supporters may rely on it that we shall take the field with men who can and will play football and good exhibitions of the dribbling code will be seen at Anfield.

“Subscribers’ tickets will be ready in a few days at 7s, 6d, 15s and 21s, according to accommodation, and the prospects are very bright, and I anticipate a very satisfactory season on the old ground. Although we are the Liverpool club, all the old playing members of the old Everton, to whom Evertonians are much indebted for promoting the game in our midst, have been elected honorary life members. The plans for the dressing rooms and gymnasium are now under consideration, and visiting teams will be spared the trouble of dressing away from the ground, whilst our own players will not only have a clubroom, but admirable dining rooms and training quarters at the ground.

“In your next issue but one I hope to be in a position to give our friends a full list of our players for next season. The charge for admission to first-team matches will be 4d, and to second-team matches 3d, and only in very exceptional cases, when large guarantees are required, will 6d be charged. The ground is in better order now than it has ever been before at this season of the year, and is improving daily. We do not propose to lay the track this year, as it is too late, but a start will be made early next year.

— Yours, W.E. Barclay.”

Clearly, Barclay and Co. were ambitious men, and had every intention of matching their neighbours across the park. Their overture of honorary membership to the “old playing members of the old Everton,” couched in flattery, has the feel of a thinly veiled insult. What is known, however, is that there was no love lost between the clubs. And the feud would endure for many years, with encounters between the teams always feisty affairs.

The first encounter between the sides came at the end of the 1892 season, with both teams reaching the final of the Liverpool Senior Cup at Bootle’s Hawthorn Road. The result of the game, which Liverpool won, was fiercely contested and a protest by the Everton board would delay the presentation of the trophy to the Anfield club.

So, was Barclay Liverpool’s first manager? To answer this, we first need to understand that the modern understanding of the role of manager at a football club didn’t apply in 1892. Liverpool, like most clubs, were ‘managed’ by a secretary who took care of the administration side of the game, recruited players and selected the team on matchdays. It is often argued that Barclay shared the role of secretary with John McKenna. However, Kjell Hanssen, historian and owner of the PlayUp Liverpool website, disagrees.

“I believe that is wrong. They both held the title of secretary, but not together,” argues Hanssen.

“The meaning of a football manager has evolved. Before Shankly there were different rules and roles connected with the manager’s position at Anfield. Tom Watson is probably the first man who could be described in that way, but even Watson started out as a ‘secretary’ in 1896.

“Based on reports from annual meetings, I believe the post changed around 1908. Up until then the term secretary was used for what we today consider to be a manager.”

Hanssen points to documents published in 1892 that show that Barclay was the club’s honorary secretary while McKenna is referenced as being on the committee of directors. Barclay continues to be recorded as the secretary of Liverpool Football Club in the 1893/94 Football League Rule Handbook. Furthermore, Kjell points out, Barclay is reported to have resigned the role in 1895 by the sports paper Cricket and Football Field.

Therefore, Hanssen makes a compelling argument for William Edward Morton Barclay being Liverpool’s first ‘manager’, from 1892 to 1895, when he was succeeded by John McKenna.

As such, Barclay would oversee the rapid rise of the new club. The team would win the Lancashire League in 1893, gaining promotion to the Second Division, which Liverpool won in 1894. In just two years of their formation, Barclay had led his team to the top tier of English football. However, they would struggle to cope at that level and would be relegated back to the Second Division in 1895.

It seems at this point John McKenna was persuaded to take up the reigns, until the club’s first title-winning manager could be persuaded to take the job. It seems that it was McKenna who restored the club to the First Division during his one year as secretary. Whatever the machinations at board level in the 1890s, it is clear that both McKenna and Barclay held pivotal roles at the club, and were crucial players in establishing it in the Football League.

There does, however, seem to be compelling evidence that Barclay was not part of a managerial double act with McKenna, but was instead Liverpool Association Football Club’s first ever ‘manager’. There is sadly little information available about his role at the club in the years that followed his stepping down as secretary.

It seems that this founding father would leave the club at some stage. During World War One he became a munitions store keeper before falling ill. He is said to be plagued with “pains in the head,” which became too much to bear. As a result, he tragically took his own life in January 1917. He was laid to rest in Anfield cemetery, where he remains to this day.

It was an incredibly sad ending to a life spent in the service of others and in the pursuit of sporting excellence. William Edward Morton Barclay was yet another great figure in the history of our club. One of the men who made Liverpool.

Fan Comments