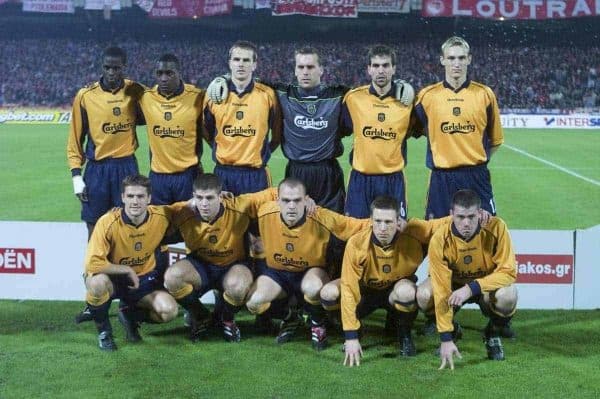

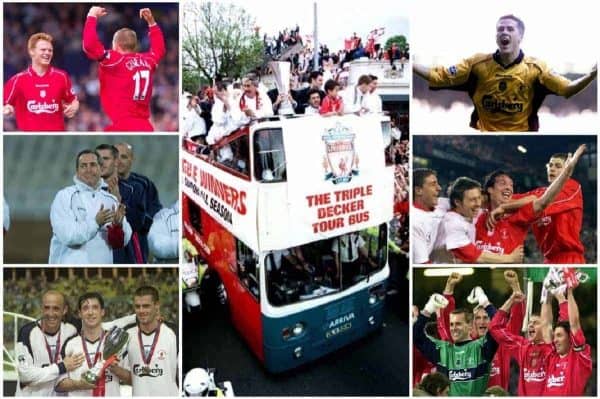

In an extract from his book ‘A Banquet Without Wine’, Anthony Stanley recounts the story of Liverpool’s 2001 treble success under Gerard Houllier.

CHAPTER 7 – HERE WE GO GATHERING CUPS IN MAY (AND FEBRUARY)

The 2000/01 was a season when Liverpool announced they were back; a breathless, joyful campaign full of twists and turns, of memorable football and last gasp goals, of celebrating wildly with scarcely believed incredulity.

It was so special because no one – absolutely no one – saw it coming. The naysayers were silenced in a frenzied cacophony of blistering and magical memories; a practical lifetime of them in the space of a few months. Gérard Houllier became a messiah, the most popular manager in a generation, as Reds everywhere – weaned for over a decade on the envy that only those who once had it all and now find themselves cast out can understand – bobbed to the tune of Baha Men’s ‘Who Let the Dogs Out?’.

It was McAllister from forty yards and his manager’s beaming, disbelieving and infectious smile; it was winning twice against United and deliriously casting off their hex over us; it was Michael Owen and a brace in Rome; it was Robbie – struggling under the authoritarian nature of the regime – still able to conjure a stupendous twenty yard volley in the first of our Cardiff visits; it was keeping out Rivaldo and company in Barcelona and completing the job at Anfield (can anyone remember the rhythm of our heart beats in those final few moments as an away goal would spell elimination?); it was practical larceny against Arsenal in the FA Cup final when Owen, like a tartrazine-addled toddler on Christmas morning, all manic eyes and disbelieving smile, tried to summersault after planting past David Seaman with his left foot; it was a deluge of goals, one of them golden, in Dortmund; it was that man Robbie again, somehow scooping an overhead kick into the Charlton goal in the final league game of the season. It was all this and more; a crystallisation of heady joy as the results just kept coming. Sixty three games in four competitions. One hundred and twenty seven goals, three trophies and a return to the promised land of the Champions League.

There’ve been worse seasons to be a Liverpool supporter.

There was no hint of the special campaign that was to come as Houllier conducted his transfer business with the revolving door policy still ongoing; ten players joined the Reds and eleven left. Save for the arrival of Jari Litmanen in January, none of the dealings of the club were particularly inspiring and the one player that came closest to capturing the imagination of Kopites – Christian Ziege – was, after a long and protracted saga where the Reds were charged with tapping up the German, an unmitigated disappointment. Symptomatic of the seemingly underwhelming nature of Liverpool’s incomings was the arrival of a veteran Scot, Gary McAllister.

Reds’ fans were more than a little sceptical at the acquisition but, like so many that hailed from the Highlands before him, the former Coventry midfielder would go on to paint himself into Liverpool’s rich historic tapestry and acted as a catalyst for the glories that were to come. The German defender Markus Babbel also arrived on a free transfer from Bayern Munich. Though not a fantasia signing, it was a canny piece of business – so typical of Houllier at this stage of his Liverpool career – and was actually something of a coup.

Babbel would go on to feature prominently in the fantastic campaign we were about to witness. There was something of a faint scandal, much to the bemusement of the French manager, when Nicky Barmby made the trip across Stanley Park to sign for the Reds in a £6 million deal, becoming the first player since Dave Hickson over forty years previously to make the journey. Barmby, a clever, robust and dynamic attacking midfielder, would play his part during the historic season – particularly in Europe.

The campaign kicked off with a routine 1-0 victory at home to Bradford City – the side that had denied the Reds Champions League football on the final day of the previous season. Emile Heskey – brawny in physical stature but seemingly possessed of a fragile ego – scored a thumping winner in a display that would become typical of his Liverpool career. As the Liverpool Echo put it: “Brilliant in one moment, and leaving everyone scratching their heads in bemusement the next.”

Heskey would enjoy a fine campaign as his manager pleaded for patience from a sometimes baying Anfield crowd and unequivocally put his faith in the big striker as the perfect foil for Michael Owen (Robbie Fowler was injured, and though he would return to action soon, he would have a frustrating time of it. Indeed, it would be the end of October by the time Robbie would start for the Reds).

Heskey thrived on confidence but sometimes this confidence was a very delicate thing; capable of all kinds of goals – lobs, headers, long shots, close range finishes – and a genuine thorn in the side of any defence when on song, too often the forward went missing, particularly as his Anfield career progressed (although it must be noted, this was the only season he played as an out and out striker for the entirety of a campaign and the results weren’t half bad).

Fowler was of course a different matter and, clearly, something wasn’t right with the darling of the Kop. This deserves some exploration at this stage as the whole Robbie/Houllier dynamic, the offers for the player from other clubs during the campaign, the apparent growing tension behind the scenes, was a major underlying theme of the season’s narrative for many in the stands and throughout the Liverpool-supporting world. Relations between the striker and Houllier had been, to say the least, strained for some time. In February 1999, Fowler had indulged in crass, homophobic baiting of Graeme Le Saux and followed this up a few weeks later with the infamous ‘cocaine-sniffing’ scandal after scoring against Everton. Having been subjected to the familiar ‘smackhead’ taunts from the Blues’ support, the Liverpool forward celebrated his goal by getting on all fours and pretending to sniff one of the painted white lines on the Anfield turf. It was, to be fair to Robbie, witty if ill-advised, but also understandable – to a degree, a gesture made in the spur of the moment.

Houllier, in trying to repair the damage, made things worse at his press conference when he, almost surreally, claimed that his striker’s actions were a homage to Rigobert Song, the Cameroonian defender who, according to the Liverpool manager, regularly pretended to eat grass – apparently an African custom – after scoring in training. This was naive and cringe-inducing for Houllier, although there should be some sympathy for a manager still new to the scrutiny in the English game and seeking to make excuses for his wayward star (and possibly prevent a ban).

According to Fowler himself, this was the beginning of the end and the reaction from the media to the Reds’ boss’s excuse sealed the striker’s fate; Houllier would, allegedly, never forgive Fowler for being the source of the extreme embarrassment he felt at being a target for the delighted amusement of Fleet Street. In his autobiography, Fowler claimed that a sympathetic (to Robbie) journalist had disclosed:

“It must have been fully two years later when he (Houllier) told a mate of mine how I was finished that day, when he had been ridiculed for defending me… Then he referred back to the ‘eating the grass’ incident and he let rip. ‘I tried to defend your mate, I tried to fucking defend the idiot and what did you do? You ridiculed me. I was made to look ridiculous because of Fowler, and I defended him. I tell you, I will never make that mistake again.”

There is an undercurrent of bitterness in Fowler’s autobiography when referring to, as he called the Liverpool boss and his number two, Jekyll and Hyde. Robbie clearly felt he was always being forced out, that he and Jamie Redknapp were the last of the Spice Boys, a legacy of an era of ill-discipline and that he was fighting a losing battle from the day the French manager walked in.

But Fowler’s injury problems were compounded by alcohol (indeed, Houllier, famously averse to the demon drink, directly blamed his striker’s fitness problems on over-indulgence. According to Jamie Carragher, the Liverpool boss thought even an ultra-professional like Roy Keane could be improved by abstinence; Fowler, caught up in nights out and rows with bouncers, was clearly doing himself no favours given the nature of the new authoritarian regime).

Moreover, Robbie’s claim that Houllier and Thompson did more harm than good – at this juncture – as they set about dismantling a ‘fantastic young squad’ just does not wash. Fowler alleged that Houllier got rid of some players too early and destroyed a side with massive potential:

“Houllier got rid of Jamo, Incey, Trigger, Harky, Jason McAteer, Mark Wright, Phil Babb, Karl-Heinz Riedle, Tony Warner, Stig Bjornebye, Bjorn Kvarme and Oyvind Leonhardsen overnight and then completed the job by bombing out Steve Staunton, Brad Friedel, Vegard Heggem and such good young players as Dominic Matteo, David Thompson, Stephen Wright and, eventually, Jamie Redknapp and me.”

It’s hard to escape the notion that Fowler is guilty of that most human of emotions: fear and aversion to change. There were more than a few reasons to get rid of all of the above: dwindling form, injury, ageing, insufficient quality, and undermining the management (or all five in the case of some). It could well be a quirk of timing that led Robbie and his manager down the road of antipathy from which, ultimately, Fowler would have no escape.

Houllier, for example, got to Jamie Carragher before bad habits had truly set in and turned the defender’s career around. Was Robbie just a little too entrenched in being the star youngster, the darling of Anfield, for whom it all came so naturally and who had, for years, not completely treated his body in a manner befitting of a modern professional footballer? Houllier was never going to tolerate this and was right in constantly reminding his wayward star on the perils of alcohol. Perhaps, the ultimate tragedy for Fowler was that he was born ten years too early or ten years too late to become the absolute legend that his talent deserved. Like many of his peers, Robbie straddled the defining moments of two vastly differing eras.

So Fowler was always going to struggle in this historic campaign and had, in reality, done so for a few seasons at this stage. Bad luck played its part but – and this is by Robbie’s own admission – so did poor decisions such as the time he was dropped for the final game of the 99/00 season when Bradford City denied the Reds a Champions League berth. Fowler, after being given permission to attend a family event, and after seeing the 1-0 reversal (with more than a few units of alcohol on board), decided it would be a good idea to ring the manager:

‘So I rang him and this time I left a message. It was short and to the point:

“I’m gutted you cost me the Champions League. I hope you’re fucking satisfied in leaving me out now.”

One can imagine that this didn’t go down too well with the management. Nevertheless, Fowler was again given another chance and knew this was it; he would need to knuckle down, get back in shape – fully – and embrace the philosophy and ethos of his manager. Typically though, disaster struck during a pre-season game essentially meaning – due to all of these factors and more – that arguably Liverpool’s greatest and most natural finisher ever would be a bit-part player during one of the club’s most successful seasons. For Robbie, there was a Dickensian twist to a campaign that would yield so much for his beloved club, it was the best of times and the worst of times and as Fowler said himself:

“It was a schizophrenic season for me. In terms of trophies, I have never had a better year, and it is unlikely to be matched by very many people. In terms of my mental state, it got worse and worse as the season wore on.”

For the Liverpool squad as a whole, there was a bipolar nature to proceedings; following Heskey’s winner against Bradford City, the Reds would get beaten by Arsenal fairly comprehensively before drawing against Southampton after being three goals ahead with fifteen minutes left. Though Liverpool settled down and started churning out results, there was always a sense of slight mistrust in watching the side; a 3-0 reverse to Chelsea was followed by a 4-0 thumping of Derby County with Heskey scoring his first senior hat-trick.

The Reds were, in a nutshell, and before Christmas, consistent only in their inconsistency. After beating Olympiacos 2-0 in the UEFA Cup in early December, Liverpool then went down 1-0 at Anfield to George Burley’s newly promoted Ipswich Town (the Scottish manager was on his way to a Manager of the Year award that was frankly ludicrous given Houllier’s achievements. Apparently the domestic game hadn’t quite learned to embrace all things continental).

But it was about to get a whole lot better as the festive season beckoned. A week after the Tractor Boys humbled the Reds, Liverpool made the trip to Old Trafford, a ground that had not been a happy hunting one for years. Danny Murphy’s impeccable free kick gave the Reds a 1-0 victory and Liverpool followed up this brilliant result with a 4-0 hammering of Arsenal with Fowler finally igniting with a ninetieth minute goal after coming off the bench. The Guardian may have claimed that it was, as the headlines noted piercingly, ‘Houllier’s new dawn’, but the French manager was not getting carried away, given the relatively poor start to the campaign:

“I don’t think Manchester United will drop ten points in the second half of the season. I still regret that we are possibly five or six points short if we are to have a run at the Champions League. Even if we have beaten them, it doesn’t mean that we are at Manchester United’s level. We are not. But this team will get better in the second half of the season.”

But even Houllier could not have envisaged the degree of his team’s improvement in the campaign’s second half. Indeed, following the victory over Arsenal, the Reds would only suffer defeat in all competitions on five more occasions – out of a total of thirty-five games. This squad was evolving, improving and developing before our eyes. Westerveld – though still prone to the occasional concentration lapse (he was a Liverpool ‘keeper, after all) – gave the defence confidence and was an excellent shot stopper; Hyypiä and Henchoz’s defensive axis was watertight as they complemented each other and would sweat blood for the cause; Babbel was superb at right-back, solid but also a great attacking outlet; Jamie Carragher, after starting the campaign on the bench and then tried in midfield, would make the left-back slot his own; Hamann was a rock in shielding his defence, stalking the defensive third of the pitch, effortlessly breaking opposition probes and sweeping up with canny authority; Steven Gerrard was showing the talent and drive that would see him develop into a world class midfielder; Danny Murphy weighed in with crucial goals and was a clever, incisive passer: Barmby and Berger could be relied upon to find the net and offer attacking nous; the newly arrived Finnish superstar, Jari Litmanen, offered guile and adroit technical knowhow; Emile Heskey was having the season of his life and dovetailed brilliantly with his striking partner, Michael Owen, as the latter finished the season with an absolute bang on the way to winning European Footballer of the Year.

Robbie Fowler, new signing Igor Biscan and Christian Ziege also made telling contributions. Jamie Carragher called it the best Liverpool team he ever played in (although this was just prior to Rafa’s monolithic 2008-09 vintage). It was a side brimming with character, big players, strength, technical ability, pace and ambition.

Then there was Gary McAllister. It’s hard to mention the Scot’s influence on this campaign without referencing the hideous cliché about aging like a fine wine. But to stretch the metaphor, McAllister was like opening a bottle of fine vintage at a table and letting it breathe until the food arrived. By the time the four course meal that was the Treble and Champions League qualification was served, the wine was fulsome, integral and vital to the whole experience. McAllister became a symbol of the unlikely nature of the entire season, and emblematic of the magic of the club, a player in the autumn of his career writing himself into Anfield mythology in the space of a few short months.

And what a few months they were; a gasping, variegated, gorgeous, seemingly endless parade of two matches a week, of lacerated nerves, of moments imprinted on the collective consciousness of an entire fan base. Of cheering and of having fun. Of barely believing what was going on in front of our eyes.

Pick your memory:

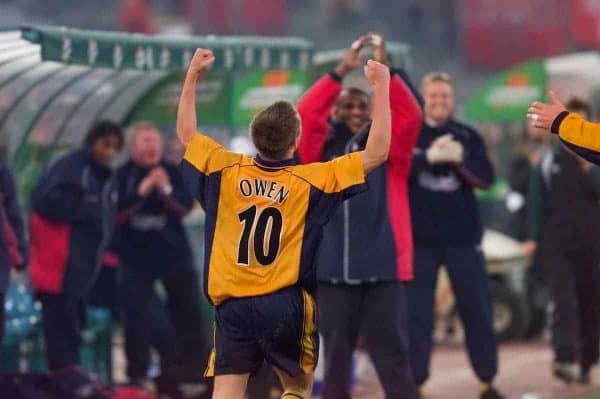

There was Michael Owen defying the odds and finishing brilliantly twice in Rome; the striker at the very peak of his predatory prowess. The return leg wasn’t exactly conducive to a steady heartbeat as the referee awarded Roma a penalty with the Italians 1-0 ahead on the night and then inexplicably changed his mind.

Then there was Robbie’s partial redemption in Cardiff in the League Cup Final as he let fly with a twenty yard lobbed half-volley that sailed over Ian Bennett in the Birmingham City goal for an early lead. But, in what would be symptomatic of the entire season, we didn’t do it the easy way and, following a late equaliser, were put through the nerve-shredder of penalty kicks, finally emerging victorious when Sander Westerveld saved from Andy Johnson.

Manchester United were beaten comprehensively in the league in late March, an extraordinary long range missile from a rapidly maturing Steven Gerrard and an adept finish from Fowler giving the Reds a 2-0 victory.

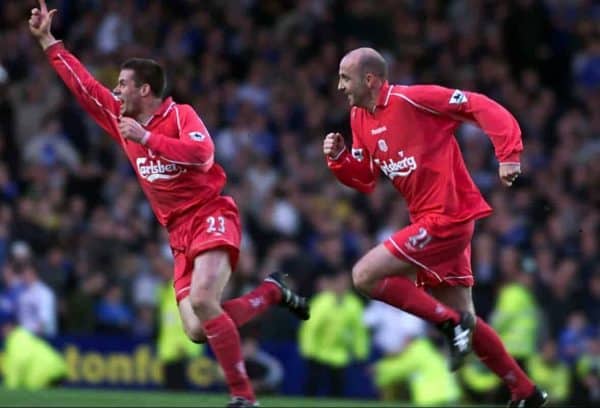

Sandwiched between two UEFA Cup semi-final epics was the 3-2 win over Everton at Goodison; an astonishing extravaganza of a match, a see-sawing rollercoaster that was settled in the ninetieth minute as Gary McAllister’s disguised forty yard free kick crept in at Paul Gerrard’s near post. The home leg of the aforementioned UEFA Cup semi-final saw Anfield return to the halcyon days of yore, all cacophonous noise and banner waving, the pitch drenched in the floodlit magic that had been gone for too long.

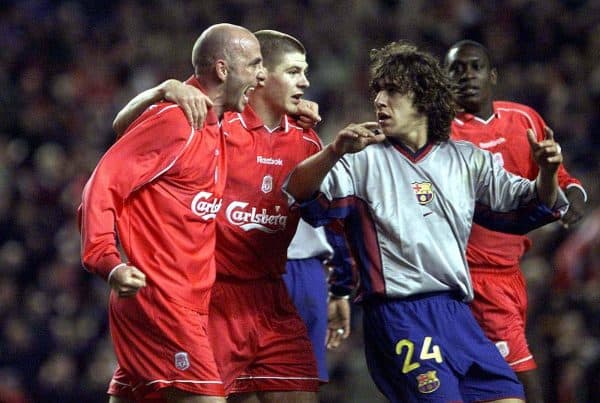

A first half penalty from that man McAllister (hit past a future Liverpool goalkeeper, Pepe Reina) gave the Reds a tenuous 1-0 aggregate lead; a goal for Barcelona would spell elimination for Liverpool. Nerves jangled and stomachs heaved as we held out for our first European final since 1985, and Heysel.

Now came the summer. May dawned with the realisation that we had two cup finals to look forward to but also, for the league campaign to end in qualification for the Champions League, we would probably have to take maximum points from our remaining four fixtures. Were we being greedy, graspingly hankering over a top three finish when the season had already been so memorable and promised more? Undoubtedly, but that is football fans, we want it all.

And, in one memorable, remarkable month, we got it.

Michael Owen and Gary McAllister scored the goals in a 2-0 victory over Bradford City that saw the Reds leapfrog Ipswich Town and Leeds United into that all important third spot (Houllier had said throughout the cup runs that the campaign was all about qualification for UEFA’s flagship; anything else would be viewed as anti-climactic if Liverpool failed in this pursuit). Four days later, Newcastle United were put to the sword, a brilliant hat-trick from Owen securing a 3-0 victory at Anfield. The England striker was coming into impressive form at just the right time and put it concisely when he told the Guardian:

“There’s an air of confidence here now, but all our success is just potential at the moment. If the season stopped now we’d consider it to have been very good, but it could yet be brilliant – a season that no one dreamt of at the start of the year.”

A 2-2 draw with Chelsea on the 8th May left many nervous; twice the Blues came from behind to ensure that the Reds would now have to beat Charlton Athletic on the final day of the league campaign to guarantee Champions League football for the following season. This effectively meant that Liverpool would now face three cup finals in the space of seven days.

Cardiff’s Millennium Stadium beckoned first; a gloriously hot Saturday afternoon, the FA Cup final template writ large in blue skies and a gorgeous green pitch, the terraces heaving, a sea of red and white. Arsenal could – and should – have been out of sight before Freddie Ljungberg gave them a seventy second minute lead. Surely there was no way back now, surely the biggest week in Liverpool’s recent history was going to get off to a depressing start? Combining flair with steel, this was a formidable Arsenal side with Vieira, Thierry Henry, Robert Pirès and the goal scorer, Ljungberg, all at their peak.

As John Williams wrote in Into the Red:

‘Okay, let’s get real; this is now officially over. We have shown little. And deserve less, and we have yet to come back from a goal down in the whole of the 2000-01 league campaign, let alone against these accomplished and experienced misers in a major final … so this begins to feel like the emptiness of the 1996 ‘spice boys’ Liverpool FA Cup final loss against United, another major occasion when we simply failed to turn up.’

Houllier took off Smicer for Fowler and brought on Patrik Berger for Danny Murphy but still Liverpool huffed and puffed. There is no way back here, we thought. None. Let us be put out of our misery; the writing has been on the wall from the first few minutes; Vieira has played through the young pretender, Steven Gerrard, and Henry has, with feline grace, toyed with Henchoz. But, improbably, magically, a free kick from Gary Mac and a swivel from Owen and we are level.

Out of nowhere, we are level with these aristocrats of passing and authority. They couldn’t finish us off; we refused to wilt in the sun, and suddenly the entire mood and dynamic shifts. There is an air of inevitability as five minutes later, Berger hits a ball towards a scampering Michael Owen. Adams and Dixon are favourites to get there but our little England striker outstrips them and with his left foot steers an unerring arrow past Seaman. From the moment the ball leaves Owen’s foot, we know it’s in and we have robbed this fine Gunners side of the FA Cup. There is no guilt, only exhilaration as vice-captain Robbie and the perennially injured club captain, Jamie Redknapp, together with the colossus Sami, lift the trophy.

A few short days later, most of us having barely recovered and still practically bronchial, the Reds were off to the Westfalenstadion in Dortmund. The opponents were the Spanish side, Alavés, and a low scoring, cagey affair was confidently and sagely predicted by most. Nine goals later, extra time and a Golden Goal and, again, shortness of breath was a malady felt by all. It was an epic European final, one that, for excitement and drama, would only be outdone by events in Istanbul four years later. The match had initially looked like being a formulaic affair as goals from Markus Babbel and Steven Gerrard had given the Reds a 2-0 lead by the sixteenth minute. Iván Alonso pulled a goal pack but, after Owen was pulled down in the box, McAllister restored Liverpool’s two goal advantage from the spot.

Half-time offered some respite and Kopites felt secure and satisfied with how the game had gone. Six minutes into the second half and it was 3-3 as Javi Moreno scored twice. This was now another exercise in palpitations and fluctuating blood pressure, as the game ebbed and flowed with both sides showing impressive attacking intent. Robbie then entered the fray and scored a magnificent slaloming fourth that was surely the winner in the seventy third minute.

But this incredible season had more twists for Kopites and with the clock ticking down, with whistles starting to mingle and merge in the stands, Jordi Cruyff headed the Spanish side level. Extra time then, as the emotional wringer tightened. Owen had been substituted and now the Reds missed his pace and the outlet he supplied; the game had become a war of attrition, a game of chicken and we watched on, grim-faced, to see who would blink.

With less than a minute left and after sitting through thirty minutes of gut-wrenching torture, Delfí Geli inadvertently headed a Gary McAllister free kick past his own keeper. The stadium erupted but the players seemed unsure; it was probably the reaction of the fans that reminded those on the pitch wearing red that they had won the UEFA Cup by a Golden Goal.

The season wasn’t over yet. Three cups had been secured but still confirmation on qualifying for that elusive Champions League waited for us. There had to be a sting in the tail, footballing campaigns were surely not this memorable and glorious.

Charlton Athletic gave their all in the first half of the final game of this marathon of a season but once Robbie Fowler had put the Reds in front with a stupendous piece of impudent improvisation, there was only going to be one outcome. The game finished 4-0 and Liverpool fans were left to reflect on the momentous achievement and staggering few months that they had been privileged to witness.

A Banquet Without Wine traces a quarter of a century of an almost unremitting series of highs and lows for Liverpool FC. It encompasses the people – players, managers and owners – the games, the trophies and agonising near-misses, a court case and near-administration, a miracle in Istanbul and much more.

* You can purchase ‘A Banquet Without Win’ at The Tomkins Times, here.

Fan Comments