Jurgen Klopp has stuck steadfastly to his 4-3-3 shape this season, but he might need a rethink in midfield to protect a fragile defence.

The fallout from the defeat to Tottenham has centred largely around which changes in personnel the Liverpool manager should make in the back five.

It’s a fair discussion to be had of course, with both goalkeeper and those in the defensive quartet at fault not just at Wembley but throughout the campaign, but it’s not the only issue to consider.

Ahead of the back line, the midfield has been lacking in key areas once again.

There’s a real struggle to cope with runners from deep—a lingering, ongoing issue as old as the Reds’ set-piece problems—and the lack of a natural defensive midfielder has an obvious downside at times.

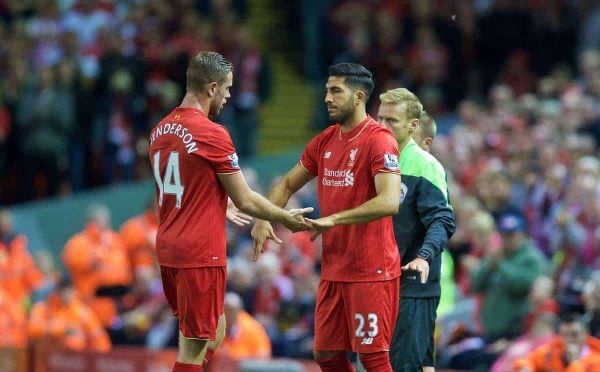

Both Jordan Henderson and Emre Can have had excellent games as the No. 6…but at times they have also been left woefully exposed by a lack of reaction, poor positioning or simply by not working in tandem with each other in the three.

Not putting pressure on the opposition, in the system Liverpool play, is pretty much suicidal on-pitch behaviour.

There isn’t the organisation, the leadership or the consistency in the centre-back positions to simply assume they’ll deal with every threat, and the Reds have been punished accordingly.

So, a change in midfield could stem the initial danger before it ever reaches the defensive third of the field.

Double pivot

Liverpool’s 4-3-3 is rather flatter in the centre of the park than is usually seen.

Consider (only for common knowledge, not for direct comparison of ability) Barcelona‘s shape in recent years: Sergio Busquets is noticeably deeper, often between or taking possession from the centre-backs, rarely venturing into the final third but always in space and playing penetrative passes.

He covers, he sits, he sweeps horizontally to recycle the ball.

Ahead of him the No. 8s—Andres Iniesta and Ivan Rakitic mostly in the Luis Enrique years—would pull the strings, link with the forwards, work the channels and rotate the direction of play.

Liverpool’s tends to have all three much closer together, with less driving on toward the penalty area unless utterly dominant at home, and there’s also an amount of rotation: Gini Wijnaldum might sit in while Henderson pushes on and presses, or Emre Can could be deeper for a spell.

While there’s nothing inherently wrong there, the issue is that they’re easily bypassed by a direct pass, there’s a lack of decisive play at times in challenging back and, as mentioned, one holder is unable to track runners from deep at times.

Adding a body and playing a double pivot solves two of those issues.

One can still step out in defensive phases to close down, while the other protects the defence; against counter-attacks, both should be in protection mode, always a little deeper, closing off passing lanes.

Of course there’s a downside in terms of swarming forward after a counter-press, but Liverpool must fix their defensive frailties first and foremost.

Protect with an extra body, potentially leaving Philippe Coutinho as a No. 10 to still help centrally but find space to be an out-ball, and the back line shouldn’t be as exposed quite as often as they are.

Flat four, in from out

A 4-4-2 has fallen far from fashion in the eyes of many, but here we’re not talking pacy wingers hugging the touchline and whipping in the crosses.

Forget that, this is more a narrow, compact version in the manner of Atletico Madrid (again, positionally speaking rather than in a football style or quality comparison).

The two in the centre are primarily responsible for forcing attackers backward or wide, ball-winners who are also expected to work relentlessly the entire length of the pitch.

Outside of them two more creative hubs play inside on the diagonal, moving from the channel into the zone where a typical No. 8 or No. 10 might rove, aiming to find spaces between the lines and link play with the attackers.

Out of possession it’s tight, easy to regain shape, difficult to break down if the work rate is there and can both present high blocks to counter-press, or sit low and ask teams to break them down by shifting the ball quickly.

The downside for Liverpool in particular is that it would require one of Mohamed Salah or Sadio Mane (when fit) to find a different role in the team, presumably as one of those in-from-out attackers.

Coutinho is a natural such option, Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain too, and every central option should be able to pair up reasonably well—but it’s still detracting from that lightning front three working in tandem, as one has to operate on the opposite side.

Diamond

Finally, there’s one more option—and it has proven both popular and successful for Liverpool in the past.

That’s to switch to a diamond midfield, which in the current case of Klopp’s side would essentially entail inverting the attacking triangle.

Roberto Firmino would drop from a forward to a supporting player, while the Mane-Salah partnership could be used as true forwards, stretching defences in the channels and encouraging them to run beyond as often as possible.

The more they do that, the more room there is for Firmino to scheme, for the No. 8s to exploit spaces and the full-backs to get upfield.

On the defensive side, think back to under Brendan Rodgers: Henderson and, at the time, Joe Allen filled the sides of midfield with spectacular work rate, backing up the full-backs and initiating counters from deep.

It’s a real change for Firmino’s role of the last year, so perhaps not ideal for him, but defensively once more the likes of James Milner, Can and Oxlade-Chamberlain have the energy, enthusiasm and positional versatility to work both centrally and in the channels.

Any might work, in any particular game. Liverpool should have flexibility to their approach, and so far they haven’t shown much this term.

That’s fine if it’s working, but three wins from nine suggests it’s not, at least not as often as it should.

The only sure-fire bet which won’t work? Keeping things exactly as they are, making no changes to system or personnel, and hoping for the best.

Fan Comments