One of the most revered men in club history, Kenny Dalglish has earned both of his titles: first came the King, now a deserved Sir.

It’s the summer of 1977, August. The sun is blazing and there’s Union Jack bunting still hanging from some of the telephone wires in my road.

The silver jubilee celebrations and street parties are behind us, but some can’t be bothered taking all of the flags down.

We didn’t mind displaying the nation’s emblem in Liverpool, back then.

It had been a great summer already. The weather was great and memories of the ’77 European Cup victory parade were fresh in my mind. They easily eclipsed the pain of losing to United in the FA Cup, and besides, who wanted to be kings of England when you could rule over an entire continent?

I’m on my way to the shop with my mum. I’m annoyed for two reasons; number one, she’s dragged me away from playing football in the street with my mate Dave. I’m still carrying the ball under my arm. It was a ‘casey’ and, at the time, my pride and joy. Number two, Dave had just told me he won’t be supporting Liverpool anymore.

My mother asks me, “what’s up with your face?” So, I blame it all on Dave. I wasn’t going to argue with her about going shopping. That was never going to end well.

“What’s the matter with him?” She asks, her face dripping with scorn, as if he had some kind of infectious disease.

Now, to be fair to my mate, we were just kids. I’d have been nine years old. Still, such a declaration amounted to blasphemy in my eyes, and clearly to my Mum too.

“He says we’ll be nothing without Kevin Keegan,” I explained.

Her reaction is swift and dismissive. “Keegan! He’s just a money grabber anyway. Your Dad says he’s a mercenary you know.”

I did, but I didn’t want to believe it. I was gutted we had lost Keegan. He had been my idol. An all-action hero who scored goals. What’s not to love?

My bedroom wall was covered in posters of the Liverpool squad, but the pictures of King Kevin were the biggest. This was a genuine superstar. He did adverts and even had a song in charts and everything.

My mum continues, “They’ve got that Scottish lad now anyway, haven’t they,” she says. “Is he any good?”

“Yeah, Mum. Kenny Dalglish.” Like most Liverpudlians, I pronounce it Dag leesh. “I dunno. Supposed to be.” I replied.

There’s no social media, no YouTube and only three channels on the telly, and I wasn’t allowed to read newspapers.

The only way I knew about a player was if he was playing in the First Division and I saw him on Match of the Day. I had no idea if Kenny from Celtic could ever replace Kevin, who’d gone to Hamburg.

“Well you tell Dave, Liverpool Football Club was here before Kevin Keegan and it will be here long after he’s gone.” She told me. That was it. Case closed.

Dave and me got our answer almost a year later, at Wembley.

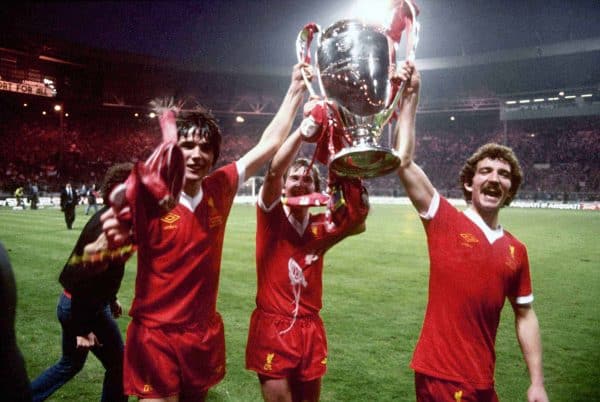

A ball from Souness and a sublime dink from Dalglish brought the European Cup back to Anfield.

Kenny’s coronation was complete and where once there were pictures of Keegan on my bedroom wall, there would now be images of his replacement.

I can still see those posters now, clinging with the hospital tape that found its way into my Mum’s uniform pocket, to the wood-chip wallpaper next to my bed. His kit is a blaze of red, the ball is at his feet, the faded crowd in the background roars him on still, in my mind’s eye.

As a player, from that moment on, Kenny Dalglish had no rival for my affections. He could simply do no wrong.

Now it’s May 1978. I’m stood trembling in my junior school assembly hall. This is Monksdown County Primary School, Norris Green, Liverpool. I’m getting ready to read out an essay I had written. I say essay, it was one side of A4 paper and written in colour pencil.

It was a piece I’d written on the morning after the European Cup final, which Liverpool had won in London. The teacher had employed what I continue to believe was a stroke of genius.

Realising that she was going to get no sense out of half the class, after such a momentous night, she decided to set us an assignment that would keep us quiet.

“I want you to imagine you’re on the team bus as it returns home to Liverpool after the cup final,” she says.

The grin on my face is as broad as Kenny’s was when he jumped over those advertising boards. In my head it was already written. “You should describe what you see, hear and how you feel.”

With that, the class went to work. You could hear a pin drop. Amazingly, I wrote that I was Emlyn Hughes, not our number seven. But, the work was all about Kenny and what he was doing and saying.

The teacher, her name was Miss Ash, by the way, seemed to like it and she chose mine and a few others to be read out our work in front of the whole school.

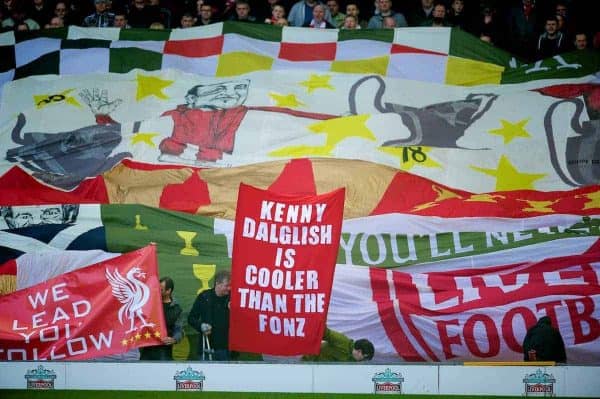

I was terrified, but as I stammered my way to the end of it my confidence grew. Finally I reached the last line, I paused, took a deep breath and confidently declared, “Kenny Dalglish is cooler than the Fonz!”

In my head there was huge applause, confetti fell from the ceiling and I was carried shoulder-high from the hall. In reality, there was polite and sporadic clapping and a few giggles.

I’d robbed the line from a Kop chant, but I didn’t care. It was true. He was. He still is.

Move forward to 1985. Kenny Dalglish has three more European Cups under his belt, a slew of league titles and other assorted accolades and trophies. We all love him so much that we’d happily walk a million miles for one of his goals.

The man has become so lethal in front of goal, that people joke that while Jesus might save, Kenny would always score the rebound.

However, the club’s reputation on the continent and at home is in ruins. 39 Italians lay dead in a crumbling Belgian stadium, after a group of Liverpool fans led a charge that caused a wall to collapse under the weight of the fleeing Juventus supporters, crushing them underneath.

I’m watching the scenes on a television screen in my parents’ living room. I’m filled with horror and the sense that things will never be the same again.

I see Kenny, he’s wearing that grey tracksuit top with the red and white stripes on it, and his face is grim and etched with worry.

In the aftermath of that terrible night, Liverpool Football Club was at its lowest point of any time in its history. It faced the loss of a great manager, in Joe Fagan, and along with all English clubs, was banned from European competition.

Our status as Kings of Europe was over.

Into the breach stepped Dalglish, guided from above by Bob Paisley. He led the club to new highs on the domestic front, as the Reds’ first-ever player-manager.

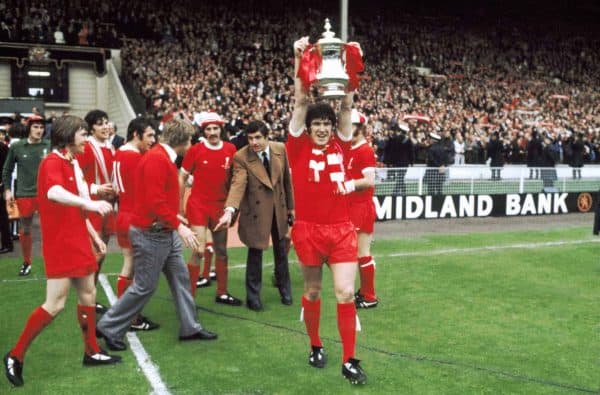

In 1986 his team would clinch a historic first league and cup double.

I was at Wembley to see that. The nation’s stadium had been our second home throughout my childhood. It’s a red and blue carnival of football. Liverpool and Everton fans have converged on the capital to show the city’s their true colours. Chants of Mersyside, Merseyside erupt outside and inside the stadium.

On Wembley way, campaigners for the 47 Labour councillors, who were battling Thatcher back home, were handing out stickers. Support Liverpool City Council, they declared. You could have one in red or blue, depending on your allegiance.

In Liverpool, there are no more union jacks flying. The city has declared itself Scouse, not English.

Inside the national stadium, Kenny and Howard Kendall lead out their teams, their faces brimming with pride.

In the stands, a city stands united, but ready for the footballing equivalent of civil war. Brothers and sisters all year round, but mortal enemies for 90 minutes, give or take extra-time and the possibility of penalties.

When the battle is finally won, Kenny, dressed in his footballer’s kit but every inch the manager and leader, parades the FA Cup in front of his screaming and jubilant supporters.

He had shown the world how to rise up from your darkest moments. How, in the face of righteous rage and almost universal doubt, you can fight for, and earn, the right to be respected again.

Under his leadership, Liverpool showed the world who we really are and what we are really about.

If anyone underestimates the scale of that achievement, it’s because they have forgotten or weren’t around to experience the soul-crushing grip of Heysel and the resultant conquest of football’s innocent joy.

Now I find myself in 1989. Liverpool and Everton are back at Wembley. The Reds are about to win another FA Cup, but I’m not there.

It’s been an exhausting season, filled with the all-consuming horror of Hillsborough. I couldn’t face travelling. I didn’t want to be involved in another thrilling chase for tickets, pretending to be happy while my heart was breaking.

Earlier in the year, 96 Liverpool supporters had their lives cruelly taken from them at Hillsborough. Football had seemed irrelevant after that. It was. Like many, in the immediate aftermath, I went to Anfield. It was the obvious place to be.

The pitch is covered all the way to the halfway line. The Kop adorned with scarves and flowers.

My friend and I make our way to the terrace and climb onto the steps. Our eyes are filled with tears and we are choked as we read poetry written on pieces of paper and fixed to the crash-barriers. On some of those steel posts, the names of victims have been scratched into the paint.

It’s hard to describe the pain, to do justice to the hurt and the anguish. We were literally on our knees, in need of help and support. We knew we could rely on each other; we didn’t expect the attacks that would come. But come they did.

Many people did heroic, selfless things in the wake of the disaster. The supporters themselves fought to save their mates, and offered comfort and support to each other in the days and weeks that followed.

The players and the manager went to funerals. They visited survivors in hospital and doubled as grief counsellors along with their wives and girlfriends. Everton supporters rallied in solidarity, as did their club.

Most of all though, while all around us the lies and vitriol was flying, when the risk of self-doubt was high and our community could have easily fractured, we had a leader. A man who understood us and our city. Someone who knew that his job now was to rise above football and hold together a shattered city.

Years later, while reading his autobiography, My Liverpool Home, I would be moved to tears by these words:

I knew too, that I had to stand up and take a more public role and speak to the press, something I was uncomfortable with. I acted spontaneously, honestly and straightforwardly, dropping my guard and talking as a parent, not as a manager under scrutiny for his tactics. The reason for the way I responded was because the people of Liverpool were, and always will be, part of my family.

Kenny was there when Kelvin MacKenzie asked him to assuage the city’s anger at the infamous and diabolic front page he personally had ordered.

Dalglish told him he would have to print another one saying the evil rag had lied, otherwise there was nothing Kenny could do to help.

When inmates at Walton prison became unsettled by Mackenzie’s headline, the governor of the jail called Kenny for help. Dalglish went in there and spoke to them, calming them down and assuring them he was there for the city and all of its people.

This was a man in transition from footballer and manager, to leader of a community, and he was doing it all at great personal cost to himself.

By the time the club found it within themselves to play football again, the game had lost some of its appeal to me.

We reached another final though, so I watch it on TV. The windows of our house are plastered in newspaper posters and pictures of the players. My mum has made sure we showed our support for the lads, in the same we had for every final in the past.

Outside, in the street, you can tell family allegiances by the colour of the decorations in their windows. Some even have red windows on the ground floor and blue ones above.

As the action unfolds, I start to feel it again. That desire to win is finding its way back. I want Liverpool to triumph, for the 96, for the survivors and for all of us.

It’s a titanic struggle and Everton do themselves proud, as they fight for every inch, twice equalising. We never expected or wanted them to lay down and they didn’t. Liverpool edge it 3-2.

In the end though, it’s the sight of Kenny that fills my heart to bursting. His thick padded jacket and that beaming smile. Football was back. We had the fight of our lives on our hands. It would take decades to win, but we could do it. We were on the march with Kenny’s army.

Two years later, in 1991, the Reds are battling it out on a number of fronts. None of us realised the inner turmoil our manager was enduring.

A gruelling 4-4 draw with Everton at Goodison Park is seemingly the catalyst for his shock resignation. In truth, Kenny had been carrying the scars of much earlier battles for too long.

I am walking from work to the bus stop with some mates. The news had reached us earlier via a supervisor who had taken a call from her friend. She had announced to a shocked office that “Dalglish has resigned,” and we were still reeling.

It’s hard to believe now, but some have already begun to question Kenny’s tactics, team selections and signings.

In particular, the arrival of David Speedie raised eyebrows. Still the shock and upset at the thought of a Liverpool without Dalglish is palpable.

In many ways, the club took a long time to recover from the loss of Dalglish. That in itself is testament to how he, through force of will, talent and personality, had held it together in aftermath of Hillsborough.

Many, including Alan Hansen, felt that the team that entered the 1990s was the most limited they had played in, but Kenny still led it to a title and, on the day he resigned, that same team was in the midst of another championship fight.

Things were very different after that though, and Liverpool would struggle to replace him.

Now I’m in 2012. I am at Wembley with my son, who wasn’t even born in 1991. Liverpool are in the League Cup final and once again Kenny is our manager. He is there once more, to answer a cry for help from the club.

We’ve been through a torrid few years and even flirted with administration. All around the club there had been frowns. In the stands, in the dressing room and the boardroom.

The Anfield hierarchy would finally realise that the man in the dugout, Roy Hodgson, wasn’t fit to be there and they had brought back a King to rescue us from mediocrity.

Suddenly we were all smiling again. There was someone at the top who understood us, who knew what the club was all about and would fight our corner. It was an inspired move.

Within months Kenny had taken us to a cup final. He would get us to another before the season was out too.

It was a risk for him, but the much bigger risk in his mind was not being there, not helping and seeing his people suffer yet more heartache. So, he took the risk because we have always been part of his family.

He gave my son his first and second cup finals. He also gave him a glorious day at Wembley to witness the Reds beat Everton in a semi-final.

Thanks to Kenny, the man whose image adorned my bedroom wall as a kid, my own child would see a fraction of the glory my eyes had witnessed.

Throughout my years of supporting this club, Kenny has been there. In glory and in failure. At our highest points and in our lowest, often dragging us up off the floor and leading us once more to new heights.

I can’t heap enough praise on the man.

In the history of this club, he is a Tom Watson, an Elisha Scott or a Billy Liddell. Kenny transcends the club and the game and embodies the spirit of an entire city; two cities actually.

His contribution over such a long period of time has shaped and defined the history of Liverpool Football Club, just as the great Bill Shankly and the superb Bob Paisley did before him.

So now, we arrive finally in 2018. The establishment have finally seen fit to recognise what we have known since the moment he first kicked a ball in a red shirt.

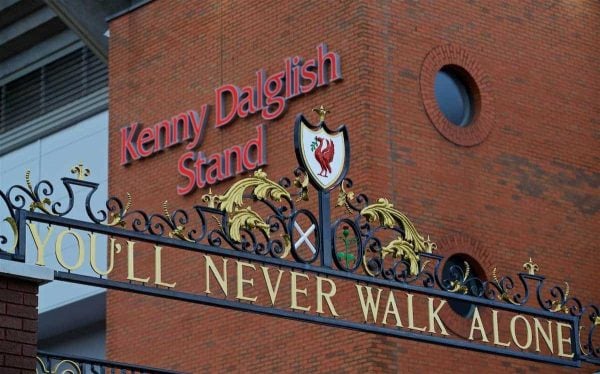

They have knighted a man who we declared was our King many years ago.

It is right and proper that a nation should honour its most exceptional citizens. Kenny Dalglish is certainly that. There can be few, if any, more deserving of this country’s highest accolade.

Whatever my feelings about the system that has belatedly bestowed this award on my hero, I am pleased for him and his family. Kenny Dalglish deserves all the recognition he gets.

So, I’m happy for the English to call him Sir. So they should.

In Liverpool though, we call him King.

Jeff Goulding is the author of Red Odyssey: Liverpool F.C. 1892-2017. Available here.

His forthcoming book Stanley Park Story: Life, Love and the Merseyside Derby, is available to pre-order now.

Fan Comments