Liverpool’s connection with Celtic is often talked about, but it’s origins aren’t as clear or as historical as is often portrayed.

The clubs are linked by players, managers, songs, and shared values between the two (generally) anti-establishment sets of fans from working class cities.

Events of 1989 created a strong bond, but prior to this a shared anthem was disputed as much as it was celebrated, and a meeting between two sides who were rising forces in European football in the 60s wasn’t exactly laced with respect.

The Cup Winners Cup tie of 1966 was fiercely and at times bitterly contested clash during which fans from both sides pitted their wits against each other.

Rather than being a meeting of two friends, it was a clash between two sides with great ambition, and thanks to the quality of the managers involved it was also a tactical battle.

According to The Celtic Wiki “both men showed the same deep concern about the game and showed a tactical nous rarely seen before.”

Before the first leg at Celtic Park, which the home side went on to win 1-0, a small group of Liverpool fans broke into the stadium for a kickabout, only to eventually be kicked out themselves by the police.

In the return leg the supporters erupted after the game as bottles and cans were thrown onto the pitch. There are differing reports as to the reason for the commotion, but most cite the main cause as a late disallowed goal for the visitors.

By all accounts none of it was malicious, and reports from the day point to the Celtic fans enjoying themselves throughout the city on their way to Anfield in a way many Liverpool dwellers would probably respect, and be familiar with.

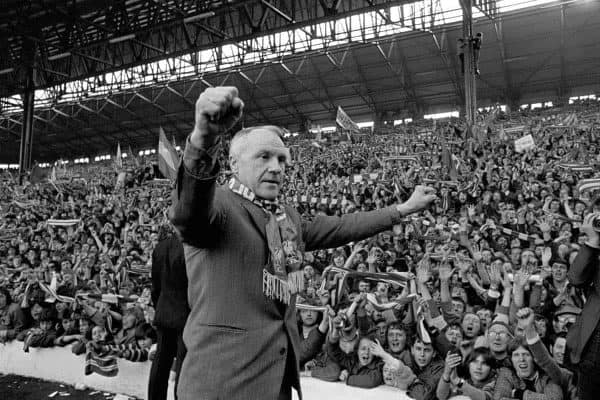

The managers of the respective sides, Liverpool’s Bill Shankly and Jock Stein of Celtic, had great mutual respect for each other, and after the bottle throwing at the end of the tie Shankly quipped: “Jock, do you want your share of the gate money or shall we just return the empties?”

The shared values of the two managers reflected the makeup of the cities they represented. Both were working class settlements built on industries brought to them by the rivers they sat upon.

The Clyde in Glasgow and the Mersey in Liverpool naturally brought industry related to shipbuilding and seafaring, but other industries attracted to these thriving areas which facilitated the distribution of goods created a large working class population in both cities.

Shankly and Stein were both working class Scotsmen from coalmining heritage, and they transferred these values onto the pitch by instilling them in their players.

A year after the sides met in the Cup Winners Cup, Celtic became the first British side to lift the European Cup when they beat Internazionale 2-1 in Lisbon.

Shankly was there to congratulate his friend after the game. “John, you’re immortal now,” stated Shankly in typically emphatic style.

It’s around this time that both clubs adopted ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone‘ as their football anthem.

In 1964 a Liverpool tour of the east coast of America coincided with a Gerry and the Pacemakers tour of the same area. Fans had already sung the hit on the Kop in the previous season when the pop chart were played over the PA system before games, but this coinciding trip to America consolidated the track as a Liverpool song.

“Gerry my son, I have given you a football team, and you have given us a song,” said Shankly after the band’s performance on the Ed Sullivan show.

Celtic picked it up shortly after, and it could regularly be heard throughout their domination of the Scottish league between 1966 and 1974.

There are still disputes as to which team adopted the song first, but the local connection with Gerry and the Pacemakers, and the fact neither club is likely to have picked up on the original — a song from the Rogers and Hammerstein musical, Carousel — gives Liverpool more of a claim to it.

But events in 1989 dismissed any notion of owning the anthem, and it became a shared tribute to those who lost their lives in the Hillsborough disaster.

On April 30, just two weeks after the tragic events in Sheffield where 95 had lost their lives (Tony Bland became the 96th in 1993), Liverpool were invited to Celtic Park for a memorial match to raise funds and spirits.

The event was an emotional one, but also an important one for Liverpool who were yet to play a game since the disaster. It created strong ties between the two clubs which lasts until this day, and if the connection between the clubs prior to this game was a loose one, the emotion poured out on this day strengthened it.

It was a show of solidarity between to like minded cities, football clubs, and sets of supporters.

It was “a new beginning for the pride of Merseyside,” wrote Allain Laing in his report of the occasion. “Not for a moment did they walk alone, as a huge crowd of fans, neither barrier nor prejudice to divide them, once again made the song an anthem rather than a requiem.”

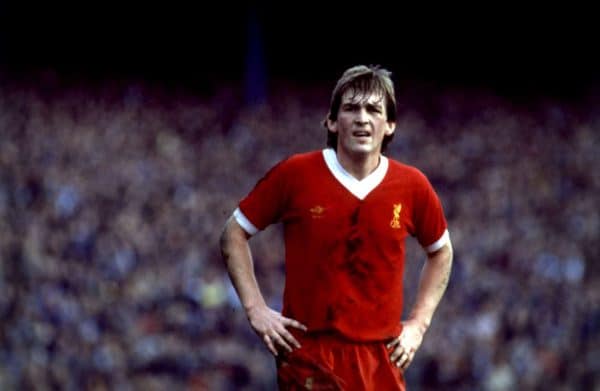

60,437 fans filled the Glasgow stadium as Kenny Dalglish — a legend at both clubs — played his first game in over a year. He opened the scoring and received a standing ovation when he was replaced by John Aldridge with just under an hour gone.

It was also an important day for Aldridge who had questioned whether he would ever play football again after witnessing events at Hillsborough. The thought must have crossed the minds of many of the players, but this game seemed like an appropriate way to return to action, and it raised around half a million pounds for the disaster fund.

There was no taking of sides on the day. No winners or losers. Fans cheered players on both sides, and the skill of John Barnes was especially appreciated by the Celtic supporters. Hugh Keevins wrote in his match report that “Barnes, whose variety of ways to worry Peter Grant drew applause from the Celtic support.”

“Over the years we have had a happy relationship with Celtic but that relationship has become much warmer today,” said the then Liverpool chairman, John Smith. “I can’t speak too highly of the warmth between the two clubs and also between the two cities.”

The game showed how revered Dalglish was, and still is, by both sets of fans, and he is another reason for the link between the two sides.

They’ve met in Europe a couple of times since. The Reds triumphed in a UEFA Cup first round tie in 1997, but Celtic claimed an impressive 2-0 victory at Anfield to progress in the same competition in 2003.

These games were nowhere near the level of Shankly vs Stein, but the 1997 game did see one of the best goals scored in the fixture when Steve McManaman scored a last minute goal which eventually saw Liverpool through on away goals.

This 2-2 draw at Parkhead was massively hyped prior to the game, and luckily the match lived up to its billing. McManaman’s dazzling solo effort was the icing on the cake after other good goals from Michael Owen, Jackie McNamara, and a skilfully won penalty from Henrik Larsson.

Prior to the 2003 games both sets of fans sang ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’, and the half-and-half scarves, for once, didn’t look out of place.

These games were still dubbed battles, and there was no time for niceties once the games got underway despite an obvious increasing bond between the two clubs.

In some ways the Liverpool-Celtic connection isn’t as clear cut as it’s often portrayed, and looking back at the history of the two clubs it’s difficult to pinpoint its roots.

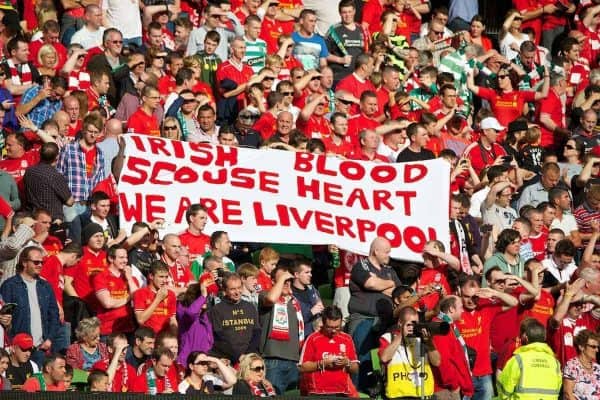

But, despite some murky religious undertones which have been much less of a problem in Liverpool than in Glasgow, the similar character and shared values of the people in these two cities would naturally lend themselves to some kind of bond once their paths cross.

This is why Dalglish took to Liverpool as he did, and why Shankly and Stein’s was a friendship built on mutual respect and common ideas.

The clubs still borrow songs from each other to this day, and while ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ went from Liverpool to Celtic, the terrace hymns sung since tend to have travelled down from north of the border.

This includes ‘The Fields of Anfield Road’ which borrows from the Celtic rendition of ‘The Fields of Athenry’, although given the Irish origins of the song there’s a good chance this could also have been sung in it’s original form at Anfield via the city’s Irish immigrants.

Both have plenty of Irish connections and fans, and this could also be another reason for the ties between the two.

But the main reason for the bond which exists between the two was without a doubt that day in 1989, when Celtic stepped forward to help Liverpool begin the healing process following tragedy at Hillsborough.

Fan Comments