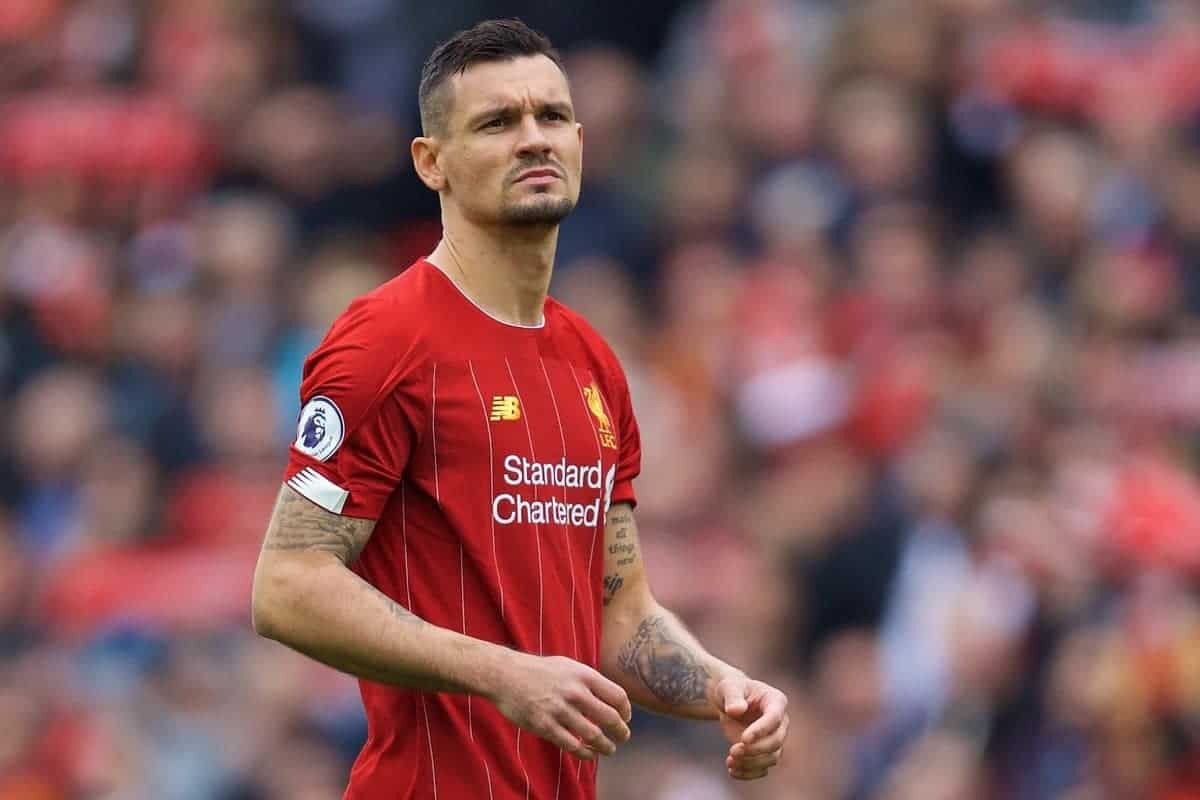

Dejan Lovren is back in the Liverpool side again after being out of favour; Rich Jolly looks at whether that’s a positive or negative after a decidedly up-and-down career at Anfield to-date.

There was a time when Dejan Lovren and Joel Matip seemed Liverpool’s answer to Phil Jones and Chris Smalling: sometimes inadequate, often interchangeable, forever bracketed together and not totally trusted by large swathes of the fanbase.

If that is unfair to the Croatian, it now feels a completely inaccurate representation of the Cameroonian.

A Champions League winner, a rock at the back and a man who has even outperformed Virgil van Dijk on occasions, his absence for up to six weeks represents a major blow.

And, for Lovren, an opportunity.

In focus

His return to the side has brought typical howls of anguish. He was definitely culpable for Stephen Odey’s admittedly irrelevant goal for Genk last week.

He was perhaps luckless in his part in Harry Kane’s rather more significant opener for Tottenham on Sunday, heading Heung-Min Son’s shot against his own bar, but his performance did not inspire confidence.

And yet, three weeks earlier, he had drawn admiring comments from Jurgen Klopp about the way he and Van Dijk had subdued Jamie Vardy. That is Lovren, forever dividing opinions.

Along with Adam Lallana, another to have provided a telling contribution in recent weeks, he is probably the player most supporters would like to see sold. And like Lallana, a man who could have joined Roma in the summer has Klopp’s confidence.

Yet in a way, he represents a qualified success: not a Van Dijk-esque triumph but an indication of Klopp’s ability to change careers.

He was a defender who could have been written off as a £20 million failure, destined to join Liverpool’s list of transfer-market mishaps.

Rollercoaster

Rewind five years and there was the sense Brendan Rodgers had bought the wrong centre-back from Southampton; in 2014-15, Jose Fonte won Saints’ player of the year award as Liverpool seemed to have squandered the windfall from Luis Suarez’s sale.

In the subsequent four years, Emre Can and Lallana became influential figures and Divock Origi mutated from substandard substitute to a part of Anfield folklore.

And while Mario Balotelli and Lazar Markovic continue to represent Liverpool’s worst bits of business for many a year, Lovren was the misfit who, at times, became a mainstay. He was not the Southampton central defender who transformed Liverpool’s defence – that distinction, of course, rests with Van Dijk – but he was a problem who became a solution.

His time on Merseyside can be traced through continental campaigns; in 2015, his missed penalty in the shootout against Besiktas meant Liverpool exited two European competitions before March.

By 2016, after Klopp had replaced Rodgers and when Lovren had started to form a partnership with Mamadou Sakho, he capped the credibility-defying comeback against Borussia Dortmund in which both scored even if, separated from his sidekick, he struggled against Sevilla’s Kevin Gameiro in the final.

Come 2018 and Lovren emerged with reputation enhanced from a Champions League final where his header set up Sadio Mane’s goal and he defended diligently. By the 2019 showpiece, he had been displaced by Matip after a season where it became clear that Joe Gomez represented the future.

In 2018, Lovren had immodestly pronounced himself one of the best centre-backs in the world; by 2019, he was fourth in line at Anfield; indeed, Van Dijk, Matip and Gomez all made more starts last season.

Now, with Gomez out of form and favour, he may clamber back up the pecking order a little.

And yet, if some of the outlandish boasts were to boost his own self-esteem, there is case for arguing the only thing that was wrong with Lovren’s assessment of the global defensive pecking order was that he said it himself.

He had a terrific World Cup with Croatia; perhaps he was a Mo Salah injury and a VAR handball away from doing the most prestigious double in the game.

The Virgil effect

Lovren being Lovren, nothing was straightforward. He returned from Russia with a pelvis injury and lost his status as an automatic choice.

Even before then, his time at Liverpool could not be seen as a simple fall and rise.

Not when his 2017-18 included a defeat to Manchester United when, in an attempt to bypass Van Dijk, they isolated Romelu Lukaku against Lovren for both goals and the humiliation of being hauled off after half an hour in the 4-1 thrashing at Tottenham; it probably replaced 2014’s 3-0 defeat at Old Trafford, complete with an unwanted assist for Robin van Persie, as a personal nadir.

Some suggested there was no way back from that. A rapid renaissance instead illustrated Van Dijk’s prowess as an alchemist. Lovren was the first beneficiary; Gomez and Matip later supplied evidence that his partners tend to improve.

And perhaps Lovren is disproportionately dependent on his partner. When he signed, Rodgers described him as “a dominant, No.1 centre-half.” He wasn’t: those words fitted Van Dijk, not the earlier arrival from St Mary’s.

Lovren’s Liverpool career can be seen in terms of partners, rather than seasons: terrific alongside Van Dijk, often decent with Sakho, perhaps miscast alongside Matip, two fine defenders who each wanted the other to be the leader at the back, and luckless enough to be teamed with Martin Skrtel, that liability who showed such strange longevity.

Part of the paradox of Lovren is that he was signed as a left-sided centre-back, the position where he excelled for Southampton, and he has been at his best for Liverpool on the right of either Sakho or Van Dijk.

He is the most multilingual member of the dressing room – Klopp admires him for his ability to communicate with everyone, if never in his native Serbo-Croatian – and yet he may have been one of the most misunderstood players in Liverpool’s recent history.

Lovren’s initial divisiveness reflected the problems of a club where too many signings struggled, where a team regressed without Suarez, where a defence was breached all too frequently and where, as the club’s costliest ever defender, he looked a figurehead for failure. More recently, perhaps it is because Liverpool did not have anything worse to worry about.

Lovren’s worst, of course, can be very bad indeed. But his best is genuinely good and if Van Dijk was the centre-back he was supposed to be, the record-breaker turned talisman, and the catalyst in improving the defensive record, Lovren proved his able assistant.

The question, as Liverpool contemplate life without Matip for a while, is if they get the Lovren of 2018 or the one of some of his darker days.

Fan Comments