As he delves into history to profile the men who made Liverpool, Jeff Goulding tells the story of an unheralded leader who recruited many of the club’s first legendary figures.

In 1908, a giant foundation stone was being laid at the Pier Head in Liverpool. In a mere three years from that ceremony, a great building would rise from the ground, standing 322 feet in height and towering over the city. It would be one of the tallest structures in Britain, and topped proudly with two mythical birds; one staring out to sea, the other inland. I am of course talking about the construction of the Liver Buildings.

Today, we don’t think of that foundation stone. It is invisible to us, but it has supported that iconic structure through fair wind and foul. Without it, there would be nothing for us to marvel at from the Mersey Ferry or as we stroll along The Strand. Perhaps, then, there could be no better metaphor for George Patterson, who arrived at Liverpool as assistant secretary in 1908.

George Stanley Patterson was born in Liverpool in 1887. Little is known of his early years, except that he was a keen amateur footballer and plied his trade for local sides Marine FC and Orrell. Somehow, though, his talents would bring him to the attention of Liverpool Football Club, and in particular their manager, Tom Watson.

Watson had been manager of the club since 1896 and had secured Liverpool’s first two league titles. He was a huge figure in the game and revered on Merseyside and beyond. When he died from pneumonia in 1915, the club immediately turned to Patterson and asked him to take the reins. His credentials for the role of succeeding such legend of the game are difficult to judge, given the sparsity of information about his qualities. It is true that there are some comical references to his clumsiness—he once walked into a tree and injured himself severely—and there is also a reference by Bee, writing in the Liverpool Echo, of his ‘wriggling bones’ and ‘big frame’. Here is the full quote:

“I am glad that Mr. George Patterson has been appointed secretary of Liverpool FC. He is a practical man, unobtrusive, and shows wisdom with pen and in football matters. He is following one of the best in the late Tom Watson, but has been well schooled, and will make good. In his football days he played a deal of football with Orrell and other clubs, but from an army point of view his big frame is useless—he has an extraordinary number of wriggling bones that have been broken. Here’s to him!”

It is not much in the way of a ringing endorsement, and its emphasis on Patterson’s administrative skills may be telling. It is worth noting that in 1915 Britain was embroiled in the First World War, and many players were on active duty. The league was suspended and organised into regional competitions, which were somewhat unceremoniously entitled Lancashire Section Principal Tournament and Lancashire Section Supplementary Tournament. Perhaps the club were merely looking for a steady pair of hands to guide them until the war was over and the league could resume.

It is true that in the early years of the game the lines between secretary and manager were somewhat blurred—something the club would resolve at the start of the 1920s, when Patterson made way for David Ashworth. Even then, though, the team would still be picked by committee. Tom Watson’s genius was said to be in his training methods, and advice to players on diet and recruitment. While there is little evidence that George understood the former, he was certainly gifted in the latter, as he would demonstrate later.

However, during the war years Patterson dealt admirably with many challenges, not least of which involved the paucity of available players. With some stationed overseas and many in barracks across the country, he would bring many talented youth players through the ranks and even persuaded a former Liverpool legend, Arthur Goddard, back to the club as a guest. He also deserves huge credit for the emergence of a number of players who would serve the club well in the 1920s, not least of which was the precociously talented Harry Chambers.

Chambers went on to play 339 times for Liverpool, scoring 151 times and was a key player in the back-to-back title wins in 1922 and 1923. However, Patterson’s managerial record during his 18 official games in charge, from the resumption of the Football League in August 1919 to the arrival of Ashworth in December, is less than impressive. He won only seven games, losing nine and drawing two. His last match in charge was a 1-0 victory over Middlesborough at Anfield, in which Chambers would grab the winner. However, Liverpool were 18th in the table and staring down the barrel of relegation. Ashworth’s arrival, and subsequent fourth-placed finish, puts Patterson’s performance in stark relief.

However, it is perhaps notable that the club did not dispense with his services altogether. It is possible, even likely, that he would have had a hand in the appointment of Ashworth as his successor. And with that act of stepping aside, he would resume the administrative side of his secretarial duties. He would continue in that role until 1928 overseeing the best of times and the worst of times.

Liverpool’s fortunes would wax and wane throughout the 1920s. Having roared into the decade with two championships, lauded by the media as the ‘Untouchables’, they would fizzle out as a force as they approached the 1930s. Ashworth would sensationally and somewhat controversially leave the Reds partway through their second title win, and would be replaced by former player Matt McQueen. When he left in 1928, it would be George Patterson the club would turn to again.

The appointment would make him the first man to manage Liverpool in two different eras, a feat repeated by Kenny Dalglish much later. The Reds continued to struggle throughout his reign, however he kept them in the First Division through some difficult times for the club financially. He would resign from his post in 1936, before bowing out of football altogether in 1938 due to ill health. He had spent three decades in the service of Liverpool Football Club.

His legacy is therefore a complicated one. While on the pitch, his achievements do not rank amongst the managerial greats of the club’s history. However, his supporting role is one that earned him much respect at Anfield and also in football more broadly. The Sunderland Daily Echo carried this tribute to his career on October 5, 1938:

“Thirty years an official of one football club! That is the proud record of Mr George Patterson, secretary of Liverpool FC.

“Mr Patterson has served the club in several positions: assistant secretary, then secretary-manager, but latterly, owing to the increasing duties and a rather severe illness he had to give up the managerial duties which were taken over by Mr George Kay, and confine himself to acting as secretary.

“During Mr Patterson’s long stay at Anfield, Liverpool have won practically every honour except that of cup winners.

“Many players who by their performances on the football field have become famous owe their position to Mr Patterson, whose foresight and ability to see the potentialities of young players was responsible for their becoming footballers.”

Kieran Smith, who works with Liverpool FC to ensure that former servants of the club are recognised for their contributions, even campaigning to ensure their graves are properly marked, believes the Sunderland Echo‘s final point about squad development is Patterson’s real legacy, stating:

“George is something of a misunderstood figure in the club’s history, yet he played a key role in its development all those years ago. He was also involved in player recruitment, helping to secure the signings of players such as Jack Balmer, Tom Bush, Berry Nieuwenhuys, Tom Cooper, Ernie Blenkinsop, Phil Taylor and Matt Busby. George served the club for over 30 years and deserves to be remembered.”

It was so often the case that other managers would reap the benefits of Patterson’s signings. Just as Dave Ashworth would polish the rough diamond that was Harry Chambers, so too would George Kay benefit from the talents of Balmer, Nieuwenhuys and others. Both managers built championship-winning teams around George Patterson’s players.

Throughout his time at the club, and in his retirement years, George lived in the shadow of Anfield. His home was in Skerries Road, just yards from the Kop. He is said to have sat on the low wall outside his house on matchdays, interacting with supporters as they passed by. He was a hugely popular figure and a significant player in the pre-war history of the club.

Following his death in 1955, Patterson was interned close to home at the nearby Anfield cemetery. His funeral cortege left from 326 Anfield Road and would have weaved its way slowly past the stadium where he had worked tirelessly for three decades, then past the streets where he had spent most of his life and onto his final resting place.

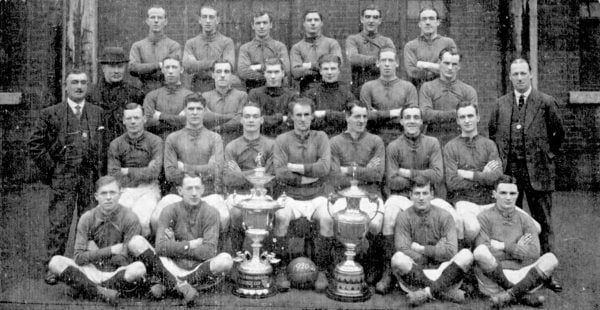

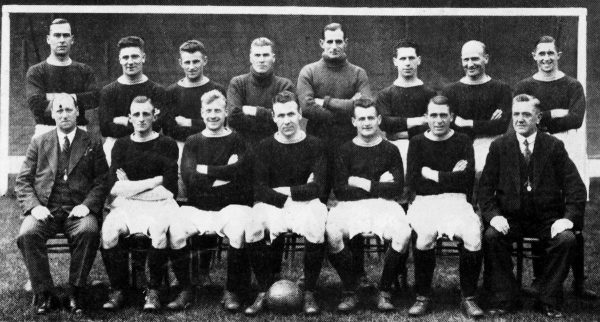

* Photo courtesy of Brian Spurgin

* Photo courtesy of Brian Spurgin

There he remained, in an unmarked plot at Anfield cemetery for more than 60 years. However, in 2019, supporters led by Kieran Smith and the Liverpool Historical Group collected the funds necessary to have his grave marked with a headstone. There it stands to this day, his record of service carved into the black marble.

George Patterson’s career at the club may be regarded by some as unremarkable, others may see him as a mere functionary. However, his long service and dedication to the cause, coupled with his eye for an astute signing or a promising youngster mark him out as a significant figure in the prewar history of the club. He will always be remembered as one of the men who made Liverpool.

Fan Comments