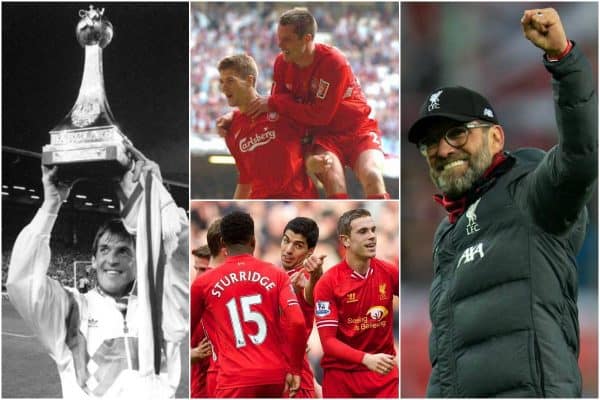

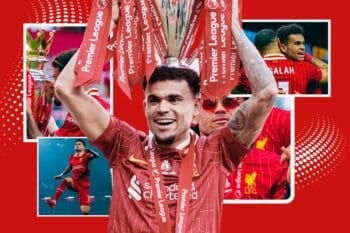

This is the story of Liverpool’s slowly forming dream, a dream thirty years in the making; the dream of league title number nineteen.

When Liverpool were finally cemented as champions following Manchester City’s defeat away to Chelsea amidst a global pandemic, it had been thirty years and 58 days since Liverpool last won the title. Amazing how it slips by.

In 1990 Liverpool did not have to dream, the dream was real; they were the most successful team in England and the league titles flowed like red, red wine.

When the title was clinched on April 28, 1990, it was the tenth in just fifteen seasons. Winning was so habitual, celebrations were muted. The dream was a reality; concrete and tangible.

Behind the scenes, however, the aftermath of Hillsborough was gnawing away at many senior figures and players, which Steve Nicol would describe to The Athletic as “a cloud hanging over us all [that] season.”

The dark clouds over Anfield accelerated the breakup of that last great Liverpool team, though no one at the time could have predicted the long road back to the top.

Emotionally drained, having carried the heavy burden of the club’s greatest tragedy, King Kenny retired, and Graeme Souness took up the mantle. A great captain, a club legend, but not a great manager. His uncompromising nature, which made him a great player, combined with a deteriorating squad set in their ways to doom his managerial attempts at revolution.

After two sixth-place finishes Souness was out the door and Liverpool’s aura, that spell they had cast over the rest of English football since Shankly’s arrival, was broken. Success and confidence are always part illusion and when the curtain finally slips, the fall is often catastrophic.

Looking to resuscitate the fading memory of success, Roy Evans was nominated as Souness’s successor, the last to emerge from the illustrious boot room tradition. With a precocious group of young and thrilling players, including Robbie Fowler, Jamie Redknapp and Steve McManaman, Evans brought the good times back in the stands. The fans had, quite literally, a new God to worship, in the shape of a local lad from Toxteth who was outrageously talented as a footballer.

In the end, Evans side – immortalised as the ‘Spice Boys’ – would only win one trophy the 1995 League Cup to go along with two third-place finishes in the league. Success eluded that team.

Carragher has recently reflected in his The Greatest Game Podcast that “they were a great team who probably should have achieved more.” They lacked an element of grit. But, that team, with its youthful exuberance, with its mix of brash, talented and local characters brought good football back to Anfield. Rollicking games were their trademark, epitomised by – the match designated the ‘Greatest Premier League Game Ever’ – a 4-3 victory over Kevin Keegan’s Newcastle.

Fondly remembered by many, this period was when the dream of a title-winning team took shape. But just as they reached a measure of success, Roy Evans team and the good times fell apart, leaving Gerard Houllier to step forth as the man to take Liverpool into the 21st century.

Hardly appearing a dream maker, Houllier completed the task Souness had hoped to achieve, revolutionising the professionalism and discipline at the club, on and off the pitch. The result was the emergence of three future club legends in Michael Owen, Jamie Carragher and Steven Gerrard and Liverpool’s most successful season since the Premier League era: the treble-winning efforts of 2000/2001.

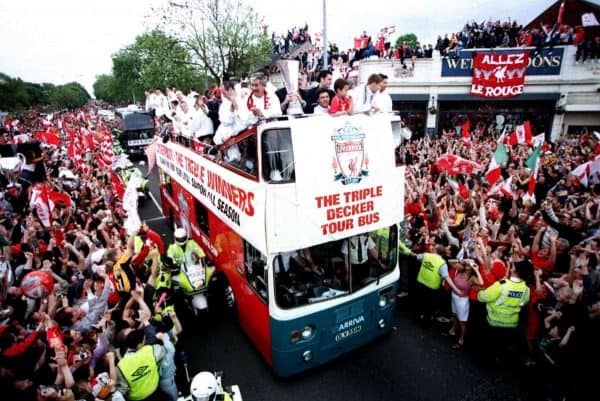

Three cup wins across three thrilling finals (League Cup, FA Cup and UEFA Cup) and a third-placed finish in the league, re-established Liverpool as a force.

The next season Liverpool went one better and finished second, with the Reds rising despite Houllier undergoing life-saving heart surgery and missing five months of the season. He returned to a triumphant Champions League quarter-final win over Roma and following a late stoppage-time victory five days later against Chelsea, which sent Liverpool top of the table temporarily, the dream had engulfed even the pragmatic Houllier. He declared to a loyal fanbase; Liverpool were “10 games from greatness.”

Just as the dream appeared on the cusp of coming to fruition, it evaporated before the faithful’s eyes, and the next two seasons represented regression and, ultimately, a bitter end for Houllier.

A legacy of mixed signings and reduced off-field clout were catching up with Liverpool Football Club. This would ensure the club was something of a poisoned chalice for potential title seeking managers, but the history and emotion of the club ensured two of the best, Jose Mourinho and Rafael Benitez vied for the role Houllier had vacated, with the Spaniard winning out.

What would follow would be one of the most improbable footballing seasons ever. The ability to dream and believe in the improbable was rewarded in an incredible way. A team that finished fifth in the league – level on points with Bolton – not only found their way into the Champions League final, but they also mustered a comeback for the ages after facing 3-0 deficit at half-time against a vintage AC Milan side.

Winning the biggest trophy in football for the fifth time, in the most ridiculous and improbable manner, banished the demons of the last fifteen years and began the Benitez era with a bang. The Steven Gerrard FA Final against West Ham followed, as did a return to the Champions League final in 2007 as Benitez assembled the best team Liverpool had possessed in a generation.

The 2008/09 season was his team’s high water mark, their high level showcased by crushing victories against Real Madrid and Manchester United across just a few days. There was a genuine feeling this might be the team. The manager. The season.

Despite Liverpool briefly seizing the ascendancy, Manchester United would rally back to beat the Reds by just four points. However, as the players dwelt on the Anfield pitch at seasons end, absorbing warm applause, it felt like the beginning rather than the end. But, while outwardly the dream appeared to be taking shape, with a first-team spine of Pepe Reina, Jamie Carragher, Daniel Agger, Javier Mascherano, Xabi Alonso, Steven Gerrard and Fernando Torres, behind the facade lurked nightmarish anarchy.

The ownership of Tom Hicks and George Gillet had turned completely dysfunctional, with the money and any sort of order dissolving away, and with them the dream. Carragher noted in the Make Us Dream documentary “Liverpool’s not just a football club, it’s an institution.” Liverpool’s American owners were treating it like a depressed, second rate asset.

Such a situation amplified Benitez’s cold attitude towards players. His aloofness had nearly caused hometown captain – Steven Gerrard – to leave for Chelsea in 2005. In 2009, it would contribute towards Xabi Alonso’s departure.

Looking back, Liverpool had been something of a house of cards, a strong manager and first team had papered over the cracks of an average squad and a chaotic organisation. The removal of one key card from the base set the whole structure tumbling back down into mid-table mediocrity.

Since Houllier’s time at the club, something of a pattern had emerged for Liverpool. Their greatest wins – ‘the Owen final’, ‘the Gerrard final’, Istanbul – had been won on raw emotion, tight tactical discipline and individual brilliance. A belief in the impossible comeback had entered the club’s DNA, but the need to overcome the improbable to attain success was indicative of wider failings.

It was as though the sleeping red giant could rouse itself for a moment, but anything more was not sustainable. What had once been a bastion approaching invincibility, a club of strong foundations had become volatile. When the manager was right, the owners or the team were not. And in the background, the dream was flickering away, always present, elusively and frustratingly unattainable.

Twenty years since their last title, truly dark days arrived, with the debt Hicks and Gillet had loaded onto the club becoming unsustainable amid the global financial crisis. A nadir was reached as the banks took over the running of the club whilst searching for a buyer, leaving Roy Hodgson presiding over undoubtedly the worst team Liverpool had witnessed since before the days of Shankly.

To go forward Liverpool had to go back, and Kenny Dalglish’s short-lived reign returned stability as the club’s new American owners, Fenway Sports Group, found their feet. Dalglish’s successor, Brendan Rodgers, in a sense continued a back to the future feel, with Liverpool regaining a ball playing style of football, reminiscent of the bygone pass and move style.

Meanwhile, the club regained its financial footing, building slowly.

Competing with the petrodollars of Manchester City, the commercial powerhouse that was Manchester United and the oligarch largesse of Chelsea appeared beyond Liverpool, but stylish football was returning.

Despite the Reds ultimately finishing seventh, in the second half of the 2012/13 season the arrivals of Phillipe Coutinho and Daniel Sturridge enabled several devastating attacking performances, such as the 6-0 destruction of Newcastle. This set a marker for the team’s potential.

There were shades of the Roy Evans years in the team’s young talent and dashing performances, perhaps, in retrospect, a foreshadowing of where they would fall short. During the 2013/14 season, the attacking powers of Coutinho and Sturridge united with an unstoppable Luis Suarez as the team’s fulcrum, a rising Raheem Sterling, a revitalised Steven Gerrard and an emergent Jordan Henderson, to create some of the most devastating football the Premier League has seen.

The team rapidly came together under Rodgers stewardship, blowing most teams out of the water with their raw firepower. Results included 5-1 and 4-0 victories over Arsenal and Tottenham and a 3-0 embarrassment of Manchester United at Old Trafford. It felt like a lasting power shift in the two Northern clubs eternal struggle. As Gerrard would reflect “the journey gathered momentum.” The dream was taking shape, almost inexorably so.

Liverpool’s main rival for the title was Man City, and their clash at Anfield on April 13, 2014, materialised as the seemingly pivotal battle. With the match taking place just two days before the 25th Anniversary of the Hillsborough disaster, a pregame tribute charged Anfield with emotion, becoming part-football ground part-cathedral, as mosaics on the Kop read ’96’, ’25 YEARS’ and ‘Dare to Dream’.

The game was a rollicking thriller, with Liverpool racing ahead, only for the Sky Blues to pull the game back to 2-2, before Manchester City’s captain, Vincent Kompany, made a crucial error trying to clear a high ball out of the penalty box. The failed clearance fortuitously fell to Coutinho who hit the ball first time into the bottom corner. Suddenly, the anxiety, emotion and tension, the twenty-four years of longing, broke like a tidal wave.

John Williams, author of Red Men, relays a supporter’s perspective, just as it felt like the dream was becoming reality:

“Manchester City had all God’s gold to build that team and when we beat them, I think everybody in the ground felt ‘my God, this is gonna happen’…it was so close, so tangibly there, and we were gasping for air in the city.”

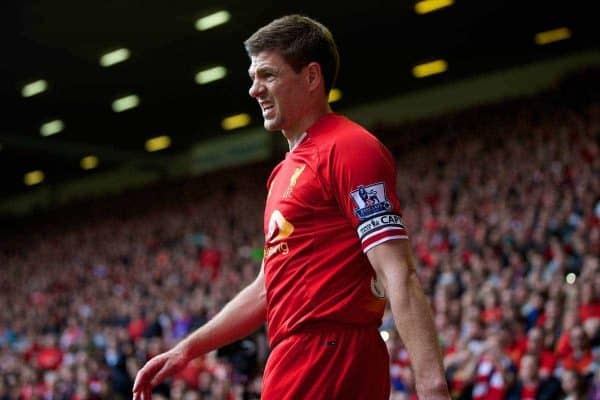

Post-match Gerrard looked to the heavens and covered his eyes as tears welled up, the emotion of Hillsborough – a disaster in which his cousin was the youngest of the 96 victims – and potential of a drought-breaking title at the ripe old age of 34 combined to overcome Liverpool’s captain.

Quickly though, he regathered himself amid the pandemonium, rallied his teammates together in a circle and uttered the famous words “this does not slip” before adding “we go to Norwich. We go again.”

It was chest-thumping stuff. If you could put it in a bottle you would label it pure, unadulterated, inspirational ‘leadership’. The message was pitch perfect, to the point where ‘we go again’ has become one of Klopp’s own mantra’s, though no one has dared mentioned slipping again.

Norwich were accounted for in a 3-2 victory before the dream slipped from Liverpool’s grasp against Chelsea. Jose Mourinho, who had sounded out Liverpool in 2005 only to be rebuffed for Benitez, thumped the Chelsea badge on his jacket in front of the Kop, in defiance, at the final whistle. For the egotistical Portuguese, who had suffered agonising defeats at Anfield, this was a moment of glee.

Few people know Gerrard had been struggling with severe back pain throughout that season, consistently requiring painkilling injections to play, but in his documentary Make Us Dream Gerrard reveals 48 hours before the Chelsea game he thought he wouldn’t be able to play; he could barely move. The pain subsided slightly, but as he reflected:

“Realistically with what I had I shouldn’t have played, shouldn’t have played. But the way I am its everything to get out there, so I had an epidural in my back and took tons and tons of pain killers.”

Once again, Liverpool dreams were shattered, this time in the most violent way possible, with Gerrard, the very personification of the club, having faltered. He had won many games off his own boot that season, and yet no amount of justifications could take away the pain, for supporters and the man himself. Gerrard’s wife, Alex, was faced with the aftermath, recalling:

“I just thought he was going to be broken. And he was. He just didn’t speak and there was nothing I could say to make it any better.”

Liverpool had won eleven games in a row coming into the Chelsea game, but the underlying weakness all season, which would cost them, once again against Crystal Palace in the following game, was their defence.

The most iconic banner of that season was three simple words ‘Make Us Dream’. It travelled around the grounds and was memorably hung over the wall by supporters at the teams Melwood training ground, as the season reached its climax.

But perhaps, upon reflection, that banner represented the unreality of the whole season, going from seventh to one of the highest-scoring teams in English history in a single year. Rodger’s team had a midtable defence and was led by a striker who had begun the season exiled to the first-team due to agitating for a transfer. The whole thing felt incredibly unlikely, and yet that had been part of what made it special.

As Liverpool came the closest to the title in nearly 24 years it equally felt all the failings and weaknesses of the Evans, Houllier and Benetiz eras had come home to roost. Success was always elusive, transitory, and it needed almost superhuman efforts to achieve. The heightened emotions and expectations formed an unsustainable partnership with the clubs reduced means.

So deflating was the failure to clinch the title that season, that even Carragher privately questioned whether he would see a Liverpool title again. With Luis Suarez’s departure post-season, the fading of Gerrard and the injury problems of Daniel Sturridge, Rodgers’ team quickly fell apart and with it the dreams of title number nineteen.

Dreaming had become not just misleading, it had become dangerous, opening oneself and the team up to inevitable pain. The nervous, anxious support Klopp would encounter, the ‘doubters’ he wished to turn into ‘believers’, was the culmination of 25 years of broken dreams.

The tumultuous times and state of the club appeared to have eroded Rodgers judgement, as he signed first Balotelli and then Beneteke, players who appeared the antithesis of the ideas he had arrived at the club with. And yet, as chaotic as the situation appeared toward the end of Brendan Rodgers’ reign, progression had occurred: FSG had learned a great deal, key personnel, such as Michael Edwards and Pep Lijnders were in place, the academy was functioning at a high level and Liverpool were playing progressive football again.

They needed someone who could unite the club, build on these foundations and overcome the growing weight of history and expectation, and failure. They needed, Jurgen Klopp.

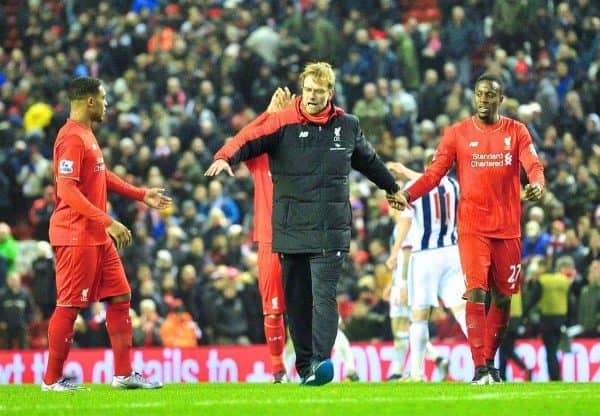

Indeed, it is questionable whether any other manager could have transformed Liverpool as Klopp has. It is easy to forget the early failures, a distant memory now, but in Klopp’s first season Liverpool lost the League Cup final to Manchester City and the UEFA Cup final against Sevilla. With the players devastated post-game Klopp’s response is now legendary, telling the players:

“Two hours ago, you all felt shit. Now hopefully you all feel better. This is just the start for us. We will play in many more finals” before beginning to sing “we are Liverpool” until all players joined in.

A result that, in the past, would have begun a downward spiral of negativity, was turned into a positive experience and affirmation of intent. It was a sign that Liverpool might have the right man to break the hoodoo.

Rather than a sudden out of the box title run, running on fumes, Liverpool have slowly and surely brought together all the right pieces, on the field and off. The manager, the team and the fans – the holy trinity as Shankly deemed them – have grown together, steadily and assuredly.

More setbacks have followed, including a devastating 2018 European Cup final loss to Real Madrid in Kyiv in and a second-place finish in the Premier League last season despite achieving the third-best points total (97) in English league history, but they have been approached as obstacles to overcome.

Speaking to the Athletic, Steve McMahon, a member of Dalglish’s hugely successful teams of the late 1980s and Liverpool’s last title-winning side, revealed that his team should have won more, with four or five winnable finals and the 1989 league title slipping through their grasp. The key to their success in McMahon’s estimation was:

“Our capacity as a club to overcome setbacks and have the courage to go again that [is what] put us at the top of the tree.”

When Vincent Kompany scored a worldie against Leicester to all but seal the title last season, Klopp’s team faced their fourth failure in as many seasons. Confronting a 3-0 deficit to overturn in the Champions League semi-final at Anfield just days later, with a weakened side, even the most resilient of teams might have lost hope. Instead, Liverpool embraced the dream of the improbable comeback locked within the club’s unconscious and did the near impossible.

Whereas in the past such moments had been false dawns, this win sent Liverpool to Madrid to win the European Cup for the sixth time, having fallen short just 12 months earlier. The blueprint was in place, the foundations were solid, for the first time in thirty years Liverpool had a team capable of overcoming their own setbacks, a team capable of fulfilling the dream.

This Liverpool team’s incredible resilience, their desire to win every game, their record points total could be seen as not only a necessary reaction to Manchester City’s excellence but a reaction to thirty years of failure. Thirty years of close calls and near misses, followed by abject collapses. Thirty years of broken hopes and dreams. Leaving anything to chance, meant having no chance.

It is no coincidence that it took a team among the finest to have played the game to finally realise the dream. Klopp has noted how this is a football club which appears incapable of taking the easy path, and the emergence of a global pandemic in the final months of Liverpool’s dream season adds an exclamation point to Jurgen’s observation.

This team is a dream team because the dream was thirty years in the making. From Fowler to Owen, to Carragher to Gerrard to Henderson and Trent Alexander-Arnold. From Souness to Evans, to Houllier, Benetiz, Dalglish, Rogers and to Klopp. From Liverpool to the world.

The dream was knitted together by many hands, its burden borne by countless shoulders. Everyone played their part, carrying the dream forth to its eventual realisation.

And now, with title number nineteen won, the dream is here. Long live the dream.

Fan Comments