John Barnes was born in Kingston, Jamaica. The son of military man, Colonel Roderick ‘Ken’ Barnes, he would go on to become one of the greatest players to wear the Liverpool shirt. This is his story.

As role models go, Ken Barnes was a formidable character. He had been trained at the prestigious Sandhurst military school, where he became a heavyweight boxing champion, before going on to manage the Jamaican national football team and represent his country playing squash. Somehow he also found time to play rugby too. Meanwhile, John’s mother, Frances, also played tennis.

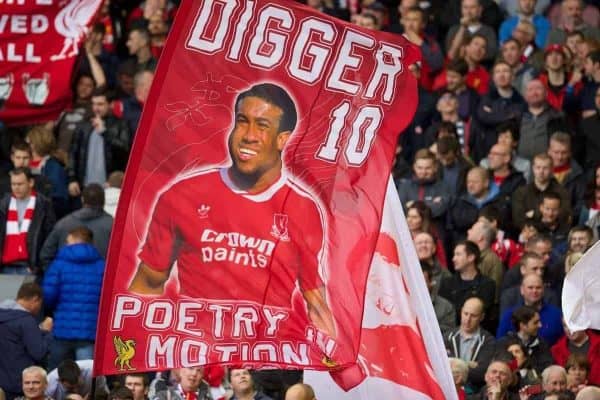

Examining Barnes’ early life, you immediately realise that this was an environment in which failure was not an option, and where the man who would be eventually be described by the Kop as ‘poetry in motion,’ was given a very solid start in life. The player himself agrees, telling This is Anfield, in an interview in 2018:

“People talk about footballers and sportsmen as role models. I disagree. I think your biggest role models are your parents.

“You don’t really think about it until you finish because you look at players you like, people in the public eye you admire but ultimately, if you have good parents they influence you, even subliminally, even without you knowing it.

“A lot of what you achieve in life is down to the way you were brought up. My Dad made me the person I am, not just the footballer.”

John owes his very name to one of his father’s footballing heroes, a Welsh footballer called John Charles who played for Swansea Town and Leeds, before going on to feature for Juventus and Roma in a career spanning three decades. He was one of the world’s greatest players.

In the mid-1970s, Barnes’ father took up a position as a military attache in the UK, and in 1976 the family would move to England. It would be a decision that would ultimately propel the youngster on a path to footballing stardom.

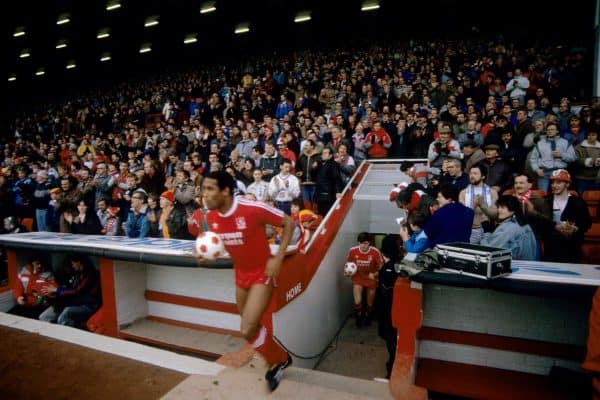

Reds come calling

Life as a child of a military parent means you can never get too comfortable anywhere. Barnes loved football, but always felt he would move back to Jamaica at some point. That meant he never entertained thoughts of becoming a professional footballer until he joined Graham Taylor’s Watford.

“I knew I would play,” he explained, “because I was good at football and I would always play. If you look all over the world, even where they don’t have professional associations, people still play football. It wasn’t until I signed for Watford at 16 that I first thought it was a possibility.”

Liverpool supporters remember Barnes as a rampaging winger blessed with almost supernatural pace and skill, however, faced with a Hornets’ side filled with attacking players, he would have to make his first steps in the professional game as a defender. If anyone expressed surprise at his position, Barnes would simply explain that he was dedicated to his craft, and would play anywhere.

However, despite his phenomenal work ethic and undoubted talent, his arrival at Vicarage Road owes something to good fortune. The late Taylor once described how Barnes had been spotted by a taxi driver while the youngster was playing for Sudbury Court.

The cabbie quickly recommended the player to Watford, the story goes that the club needed just half a game to realise they had unearthed a huge talent. They signed him up immediately. Barnes had an incredible spell with the Hornets, a period which coincided with one of the club’s most successful periods. In the 1980s, they would manage to finish runners-up to Liverpool, were beaten finalists in the 1984 FA Cup final and had reached the quarter-finals of the UEFA Cup.

To the young Barnes, there was every possibility that he could achieve all of his footballing ambitions under the guidance of Taylor. However, the call of Liverpool would be a difficult one to resist. By the time his mentor was replaced by Dave Bassett in 1987, Barnes had already agreed to go to Liverpool.

His move to Anfield was confirmed in 1987 for a fee of £900,000. However, Kenny Dalglish had approached him in January and, according to Barnes, a deal was always on the cards.

Man United manager, Alex Ferguson, once made claims in his autobiography that Bassett had offered the United manager the chance to sign him and that he had declined the opportunity. A decision he is said to have rued for many years, given it had extended Liverpool’s dominance of English football for a few more years. However, Barnes is dismissive of the idea that joining United was ever a possibility. He said:

“I’d already signed for Liverpool before Bassett took over. I never played under Bassett. I don’t know. He might have said to Alex Ferguson, ‘do you want to sign John Barnes?’ But it was already arranged for me to go to Liverpool.

“I only met Dave Bassett once. I was going to Liverpool in two weeks. He invited me to his house to say good luck. He never mentioned Manchester United. It would never have happened.”

The ‘Liverpool way’

In 1987, Liverpool were beginning yet another rebuild. They had won a league and FA Cup double in 1986, but the 1986/87 season ended in disappointment. Liverpool finished runners-up to neighbours Everton and were beaten by Arsenal in the League Cup final. It was a rare trophy-less season compounded by the impending loss of Ian Rush to Juventus.

Rush and Dalglish had formed one of the deadliest partnerships in football. They had terrorised defences throughout the ’80s. However, by 1987 Kenny had completed his transition to the manager’s position, hanging up his boots in the process. The King would have to refashion his empire.

In a rare move for Liverpool, who had built their success on adding one or two players every couple of years to a team of all-stars, Dalglish signed four new attacking players in one season. Those men were John Aldridge, Ray Houghton, Peter Beardsley and, of course, Barnes.

They would click instantly and become the rocket fuel that propelled perhaps the most flamboyant and mesmeric Liverpool team of all time. Barnes, however, was in for something of a culture shock. In particular, the simplicity of the ‘Liverpool way’, which had remained largely unchanged since the days of Bill Shankly, took him by surprise.

How would he describe the methods utilised at Melwood in 1987?

“Simple and, as far as I was concerned at the time, backwards, I must admit,” Barnes told This is Anfield. “At Watford, we had psychologists, nutritionists and top-notch methods. At Liverpool, they were just playing five-a-side football.

“But after a while, you get to learn Shankly’s way, that he got into the training, was much more forward-thinking and much more advanced than any other team. But at the time, to me, it seemed disorganised.”

At Liverpool, the emphasis was on signing players who had talent, could fit in and, more importantly, could think for themselves.

“Work it out for yourselves,” he says, explaining the philosophy of the Reds’ famous boot room. “Liverpool always signed players that they knew over a period of time had the intelligence to play football. Yes, you had to have ability, but you had to understand the game.”

To today’s coaches and managers, this may seem outdated, almost prehistoric. However, there is a method to the apparent madness, according to Barnes:

“What happens as a coach is that you train and prepare and you come up with tactics. Unfortunately, football doesn’t work like that. It’s fine, all well and good until you start the game and the opposition does something you didn’t think they would, and the tactics aren’t working.

“What do you do? Are you going to wait until half-time for the manager to do it, or, do you look to the bench and say ‘what do we do? We weren’t told about this’?

“At Liverpool, the coaches would say to you, ‘I’m not telling you what to do. Work it out for yourself’. That was a culture shock, because Graham Taylor, for 90 minutes, told us exactly what to do.

“So what I didn’t know was that in six years Liverpool had seen in me that I was able to translate that into what Liverpool wanted me to play. Liverpool saw things in players that you didn’t know you had yourself.”

Prejudice and racism

In the 1987/88 season, Liverpool and Barnes proved themselves to be the very best in land. They would sweep all before them and play majestic football. However, before he would rise to become a hero of the Kop, Barnes would have to overcome doubts and criticism motivated by racism.

At Liverpool in the 1970s, a young Howard Gayle, the club’s first black player, would experience degrading abuse from rival fans and, sadly, a teammate. He wrote passionately about it in his book, ’61 Minutes in Munich’.

In an example of how prejudice and racism would always threaten to overshadow his brilliance on the football field, Barnes would experience one of the greatest moments of his international career, scoring a wonder goal against Brazil, only to be confronted by two members of the far-right National Front sat on the same plane home draped in their banners.

Of course, there wouldn’t have been National Front banners on the Kop when Barnes arrived at Anfield. However, the demographics of the match-going fan in the 1980s was largely white, male and working-class. Many credit Barnes with changing that culture, and contributing to an atmosphere that is more diverse and welcoming today.

However, the player has always been sceptical about that, explaining that racists didn’t go away when he joined the club, they were merely silenced because of the performances he put in. Would they have kept quiet if he hadn’t have settled in or turned in a few mediocre displays?

“That’s why I state it’s unconscious racism in football,” he explains. “Because I played well for Liverpool it may have changed, but if I came to Liverpool in 1987 and I was a terrible player, I don’t think it would have changed that much.”

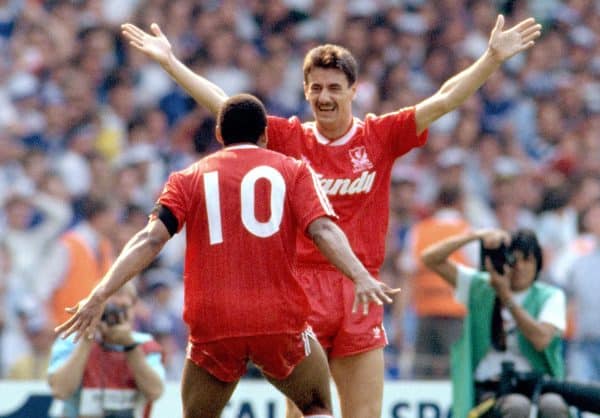

Poetry in motion

Liverpool would compensate for the loss of Dalglish and Rush by bringing in Barnes, Beardsley, Houghton and Aldridge. While they were all international players, getting them to gel while getting the team to adapt to a new system was a huge challenge for Dalglish. That he achieved it and took the team to new levels of brilliance is often overlooked.

However, Barnes would be pivotal to the success that followed, and Aldridge would later talk about how the winger’s ability to “ping the ball” to his feet or head would make the job of scoring goals easy.

Liverpool simply blew the league apart in the 1987 season, finishing champions with weeks to spare and amassing 90 points. Defences wilted in the face of their relentless attack, and the Reds conceded just nine goals at home, scoring 49. Their overall goal difference was +63, and they lost just twice.

They went 29 games unbeaten, equaling a record set by Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest. Sadly, it would be Everton who stopped them setting a new benchmark. They’d also be denied another league and FA Cup double, thanks to an inexplicable and freak defeat at the hands of Wimbledon in the 1988 FA Cup final.

In short, until the arrival of a certain Jurgen Klopp in 2015, the 1987/88 Liverpool team in which Barnes was such an influential figure, was arguably one of Liverpool’s greatest ever sides, and when you think of the success the Reds have had down the years, that’s quite an achievement.

Barnes’ Liverpool career couldn’t have got off to a more scintillating start. He was challenging stereotypes off the field and winning a whole new army of admirers on it. As the 1988/89 season got underway his life as a footballer had never been better.

After spending a few months living above a dental practice within earshot of the Kop, Barnes had now moved into a home more suited to that of a footballing superstar. He had actually only decided to move after the club informed him in writing that it wasn’t befitting a Liverpool player to live in such a neighbourhood.

There’s a sense of everything in life being carefree and simple for Barnes. Life was good, the football was better and Barnes was having the time of his life. Of course, this would prove to be the calm before a terrible storm.

On April 15, 1989, at Hillsborough, what should have been a glorious day of FA Cup semi-final football changed the lives of everyone connected with Liverpool Football Club, forever.

Barnes was on the pitch and setting up for a corner when he noticed people in distress. He would later recall waiting in the dressing room and expecting the game to get back underway, before the news of fatalities filtered through, and the horror set in.

It’s now well known that the first-team players and management rolled their sleeves up in the aftermath of the disaster. They became counsellors, attended funerals and visited fans in hospital, and Barnes would be at the forefront of all that.

His experiences at Hillsborough, and his work in the aftermath, coupled with a period of great success on the football field have cemented the relationship between Barnes, generations of Liverpool supporters and the people of Merseyside.

He would play an incredible 407 times for the club, scoring 108 times. In a space of just eight years, between 1987 and 1995, he would claim two league titles, an FA Cup and a League Cup. In addition, he would be named PFA Player of the Year and twice be crowned FWA Footballer of the Year. But for a post-Heysel European football ban, he would surely have lit up European football too.

Liverpool’s demise and Dalglish’s shock resignation at the beginning of the 1990s would see the trophies dry up for Barnes. However, the affection with which he is regarded by Liverpool fans never has. And the feeling is mutual.

Barnes maintains a home on Merseyside to this day, and when asked about his enduring bond with the area, this was his reply:

“The people. I like the people. They’re down to earth, they’re humble. It was the same with the players of the past. You couldn’t come to Liverpool with a superstar mentality, or believe you were better than anyone else in the team, or in the city. And I liked that.

“I like the fact that people don’t look up to you like you’re a god. They treat you like a normal person and I like to think that I am a normal person. For me, I want a normal life and life in Liverpool and Merseyside is a normal life. I want my children to be brought up in that environment.”

After finishing his Anfield career in 1997, Barnes would spend two years at Newcastle, before ending his playing career at Charlton. He would eventually hang up his boots in 1999, boasting a career of 586 top-flight games and 155 goals, as well as being capped 79 times for his country.

Barnes would enjoy spells in management at Celtic, Jamaica and Tranmere Rovers. However, he will forever be remembered by those blessed to have seen him live and in the flesh as poetry in motion, and one of the greatest players ever to grace Anfield.

Fan Comments