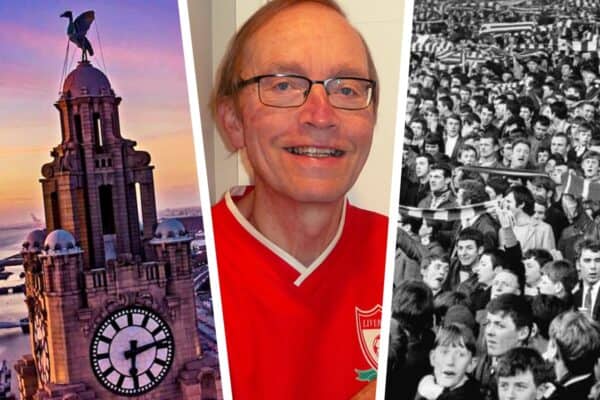

For some falling in love with Liverpool happens from birth or early childhood, for Kjell Yri, it was a gradual realisation that was always meant to be.

I finally saw the light in the mid-1980s, and it was red. Up to that point, I had been adrift in football darkness, clubless and rudder-less. Now I felt a new sense of belonging and purpose. It had not been an easy journey.

Let’s start at the beginning. In Norway during my childhood, there was no television. We relied on the radio to keep us informed. The only news we heard of English football was to do with the football pools.

Twelve First and Second Division matches were selected by the state-run football pools organisation to feature on each week’s coupon. The results of those games were announced on the radio at the end of the sports report on Saturday night.

The idea was to predict whether each tie would end in a home win (1), a draw (X), or an away win (2). If the radio announcer was running out of time, delayed perhaps by breaking news from the herring fishing grounds, the scorelines would be omitted, and we would get just a kind of Morse Code list: 11X12XX etc.

A friend of my big brother had a special respect for Sunderland Football Club, a frequent contender on the pools coupon. In our West Country dialect, we pronounced the club’s name as “Soonderrlahndd!” Always with an implied exclamation mark at the end, it sounded like an ancient Norse command to launch the long ships and prepare to invade England, again.

However, despite all that, decades were to pass before the magic of English football dawned on me.

Norway to Spurs

During the winter, my mates and I gave football little thought as we were heavily into speed skating, mainly in a spectator, or, more accurately, listener capacity. The big championship races were broadcast live on the radio.

We would crowd round the set and absorb the reporter’s blow-by-blow word pictures of our heroes as they scooted round the icy track in search of glory in far-away Gothenburg, Deventer, Moscow, or wherever it might be. In our notebooks, we meticulously recorded the lap times: 38 seconds, 38, 40 (groan!), 38, 36 (yay!) etc.

Norwegian football did not wake up from its winter hibernation until the snow had melted in spring. Inspired by the prospect of domestic First Division action, we would pack away our skates and skis, and pump up the ball, which had been slowly deflating in a corner of the cellar during the months with an “r” in them.

One year, Brann FC of Bergen captured our undivided attention when their first team came to our village, a quick half-hour stop on a pre-season goodwill tour of the provinces. Their popular star, Roald Jensen, went on to become a professional in Scotland as Heart of Midlothian’s first non-British player.

In 1963, the Beatles burst noisily onto the scene and changed everything. The music and fashion they had started on Merseyside spread like wildfire among my contemporaries worldwide. Like millions of others, I was captivated, collecting all their records. But I didn’t think to join the dots and take an interest in their home town’s football giants. The Reds won the First Division title in 1964 and 1966, but, now at high school in Bergen, I was too busy growing my hair long to notice.

I was a regular listener to shows on the BBC Light Programme, not only ‘Pick of the Pops,’ but also ‘Round the Horne,’ ‘The Goon Show,’ and ‘Hancock’s Half Hour.’ It did little to rescue my faltering academic career in solemn subjects like maths, physics, and chemistry, but it was good for English.

One of my friends played in a band, and I volunteered to transcribe the lyrics of hit songs for him. My version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Just Like a Woman’ almost certainly contained some unintended deviations from the original. Some 50 years later, Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Not that I claim any credit for that.

It was also now that the football penny finally dropped, albeit a little half-heartedly. One of my classmates was an enthusiastic Man United supporter, forever talking about English football.

Gradually, while we traded impressions from our respective fields of interest, I began to take notice of his. Jimmy Greaves was in his heyday with Tottenham. And I knew that the leader of the Dave Clark Five had been born in Tottenham. For no better reason than those, I started calling myself a Spurs supporter. It seemed to go with the hair.

Scouse connection

By the time I started high school, my mother had re-married and moved from Norway to England. I began travelling over there for the summer and Christmas holidays. I loved England from the start – the red bricks and buses, the black taxis, the policemen’s helmets, the smoke, the miniskirts, the tabloids, the pubs, the smell of sausages, and the music. However, football had not yet become important to me – my slight Spurs affiliation was more like a fashion accessory. But I did watch the 1966 World Cup final, cheering loudly for Bobby Moore and the boys.

After completing my compulsory national service by serving in the Norwegian army for a year, I moved to England in 1968. Essex, to be specific. On August 19 that year, I went to my first English game.

It was at White Hart Lane, and I watched Spurs play none other than Liverpool. It ended 1-1. From a storytelling point of view, it would have been great if an epiphanic awakening of my attraction to Liverpool Football Club had occurred that day, but it didn’t. And my lukewarm, lackadaisical support for Tottenham began to dwindle, too, as I started not only my first job but also finding my way round London’s more affordable nightspots.

The job was that of a clerk with the Standard Chartered Bank. I was with the bank for seven years, but during that time no one was to know that it would become Liverpool’s shirt sponsor in 2010.

My search for a life partner paid off handsomely when I met Louise, a beautiful and vivacious young woman from New Zealand. We moved in together in a tiny attic flat in Golders Green. We had an old Citroen 2CV that carried us on long summer holiday trips on the continent and in Scandinavia.

The closest I can come up with by way of a Liverpool connection during the period that followed was watching ‘The Liver Birds’ on television. And ‘Till Death Us Do Part,’ featuring the ‘randy Scouse git.’

Apropos that, it’s an interesting fact that ‘Scouse’ comes from the Norwegian word ‘lapskaus,’ a traditional stew popular with the Norwegian merchant marine sailors who called in at the port of Liverpool, looking for food during shore leave. The astute businessmen operating the eateries in the city were happy to accommodate the sailors’ preferences.

Then the local population in general, attracted by the mouth-watering smell of stew drifting out the pub kitchen windows, started cooking and eating it, too. The word was shortened to ‘skaus’, which was anglicised to Scouse, and a whole new culture was born.

I grew up on lapskaus. So, with that and the old Viking escapades, I had always had a personal link with Lancashire, but without knowing it, or, at least, without actively reflecting on it. My Viking ancestors put their stamp on the area long before Anfield the stadium was conceived. I apologise for any inconvenience they caused.

A love that blossomed

In 1977, we, including a two-year-old daughter, migrated to New Zealand, and this has been my home ever since. Our son, born in 1978, completed the family line-up.

After a few years in the wine industry, I started a new job in Auckland in 1984. Here, the contagious passion of two football-following colleagues led me to take up reading English football news. And I became a regular viewer of the one-hour weekly highlights package on television.

It was impossible to ignore Liverpool. Dalglish and Rush were running rampant, winning virtually everything. Like my Beatle heroes before them, they seemed to be conquering the world. I read about Bill Shankly and the Boot Room and found it fascinating.

Gradually, it all fell into place – the Vikings, the lapskaus, the Fab Four, Anfield, King Kenny. It was not a sudden lightbulb moment. It was a gradual realisation of a new condition: I was hooked on the Reds.

As a loyal Liverpool supporter, with a Gerrard t-shirt and a ‘This is Anfield’ mug to prove it, I feel I have been in Liverpool’s corner during the tragedies that have befallen the club as well as during the times of the team’s towering triumphs.

It’s been a rollercoaster ride, but I’m not getting off. ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ still triggers goosebumps. I’ve never set foot in the city of Liverpool, but I remain hopeful of visiting Anfield one day.

Meanwhile, I’ll continue to admire from afar.

* This is a guest article for This Is Anfield by Kjell Yri.

Fan Comments