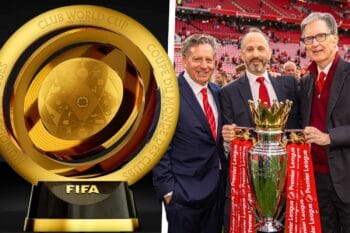

While there are understandable criticisms of the new Club World Cup, it is a reality that missing out on the next one would see Liverpool fall behind financially.

This past weekend, in the shadow of the World Cup buildup, FIFA quietly tipped its hand. The newly expanded Club World Cup – 32 clubs, polished production and marquee names – launched across the United States with all the ceremony of a global sporting showcase.

But in Liverpool, the atmosphere was curiously muted. Detached. Among match-goers who trek motorways in midwinter and live for midweek away ends, this tournament barely registered. It felt synthetic. Like a trophy made for someone else.

However, treating it as a distant distraction would be a grave mistake. Because this isn’t just about what it is – it’s about what it’s becoming.

The Club World Cup is fast becoming the scaffolding around football’s future. And Liverpool can’t afford to be left out.

A ridiculous prize pot

The financial structure alone makes that clear. The total prize pot stands at over £800 million. Every club that qualifies will receive a participation fee, but the real sums are stacked towards the elite.

Group-stage wins are worth around £1.6 million each, and even a draw earns £800,000. A place in the last 16 brings in £5.9 million, quarter-finals earn £10.3 million, semi-finals add £16.5 million, and the two finalists are awarded £23.5 million each. The winners take home an additional £31.3 million in prize money alone.

Then there’s the participation bonus – a pot of around £420 million to be shared out, with European clubs set to receive anywhere between £10 million and £30 million apiece, even before they’ve played a match.

Taken together, the winning club could walk away with up to £90-95 million – and that’s before factoring in commercial boosts, merchandising spikes, and exposure value.

Put simply: this isn’t a supplementary reward. It’s a foundational revenue stream. And unlike Champions League earnings, which arrive in phases over 10 months, this money lands before a domestic ball is kicked.

It creates agility. It empowers early transfers. It allows clubs to act – not react.

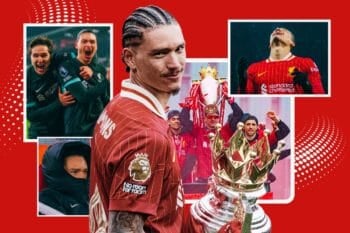

And this is why it matters. Liverpool are back on top – Premier League champions for a 20th time, with a project under Arne Slot that has momentum and direction. But sustaining that elite status is becoming harder with every season, not easier.

Because while Liverpool operate in the most competitive league in the world, rivals abroad benefit from structural advantages that compound year on year – and now, the Club World Cup is becoming one of them.

The rich get richer

This tournament doesn’t level the playing field. It tilts it further. It doesn’t just reward success – it institutionalises it. And Liverpool, for all their brilliance, are now at risk of being outspent and outpaced by clubs whose qualification is practically guaranteed.

It’s this structural tilt that should concern every Liverpool supporter. In England, Champions League qualification – let alone a place at the Club World Cup – is a knife fight. Seven clubs with genuine ambition. Five spots. And even then, one off season can shut the door. A domestic cup win won’t get you there. One slip, one slump, and the consequences last years.

But across the continent, it’s a different game. Bayern Munich have waltzed to 11 of the last 12 Bundesliga titles. Paris Saint-Germain barely need to break a sweat in France. Real Madrid and Barcelona effectively own LaLiga between them.

For those clubs, Champions League football isn’t an aim – it’s a default. That guarantee brings with it a direct line to Club World Cup qualification, and all the riches that follow.

That disparity isn’t just economic – it’s existential. Clubs like Real Madrid don’t have to plan around qualification. They don’t need to fear a dip in form or an injury crisis in April. Their access to the top table is baked into the structure.

And now, with FIFA’s Club World Cup handing out tens of millions before the domestic season begins, that structural advantage is about to harden into something even more immovable.

Liverpool will fall behind without it

What does that mean for Liverpool? It means a club built on merit – on competitive integrity, on doing things the right way – is being told to run a race with the ground shifting underneath it.

It means that even with a brilliant manager, smart recruitment, and a record of success, the club could find itself shut out of a system designed to reward predictability, not excellence.

And perhaps most crucially, the Club World Cup is not an annual chance. It’s a four-year window. Miss it once, and you don’t just lose a season – you lose four years of relevance.

Four years of commercial momentum. Four years of top-table exposure. Four years of being visible to the next generation of fans.

That visibility matters more now than ever. Because this isn’t just a tournament – it’s a media product. FIFA’s partnership with DAZN, worth over £1 billion, has made the entire event free to stream globally. Not for broadcast partners. For algorithms.

Referee bodycams. AI-powered offside graphics. Real-time VAR feeds. All of it tailored to short-form video, to clips that travel faster than commentary ever could.

This is the football of TikTok and YouTube Shorts. Of Instagram reels and autoplay goals. And it’s not a gimmick – it’s working. Clips from the tournament are outperforming regular league content. A single angle of a goal is now a marketing asset.

A team’s branding is measured by impressions, not programmes sold at the turnstile. If a 13-year-old in Nairobi, Delhi or Texas sees PSG five times a week and Liverpool once a month, guess where their loyalty forms?

It’s easy to scoff at all this from the Main Stand. To say the sport should be about atmosphere, not algorithms. But the uncomfortable truth is: both matter.

In 2025, you can’t shape football’s future if you’re not in the clips. If you’re not in the room. If your badge isn’t flashing across the screen during a 30-second highlight watched 10 million times before breakfast.

The Club World Cup is changing – and changing football

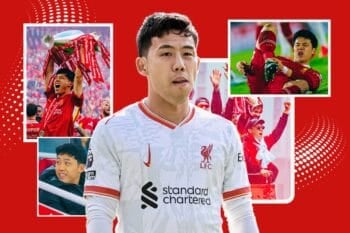

And this brings us back to 2019. Back to Doha. Back to Jordan Henderson lifting the FIFA Club World Cup after beating Flamengo in extra time.

Back then, it was an honour. A sign of global supremacy. But it wasn’t structural. It didn’t reshape anything. It was a deserved cherry on top of a historic season.

In 2025, it’s different. Being Club World Champions doesn’t just say you’re the best – it makes you more powerful. It changes how you operate. How you recruit. How you market. And how the world sees you.

Liverpool’s triumph in 2019 was a symbol. But if they miss the next cycle, it won’t just be absence. It will be exclusion – not because of failure on the pitch, but because of a format that makes it harder to come back once you’re out.

Those who qualify now are likely to qualify again. And those who don’t? They’re playing catch-up in a game where the finish line keeps moving further away.

One of the clearest indicators of the tournament’s distortion came via Auckland City – a semi-professional team from New Zealand who qualified via the OFC. They earned close to £3 million just by turning up. Then they were promptly thrashed 10–0 by Bayern Munich.

On the surface, a fairytale. In reality, a portrait of imbalance. That money dwarfs what most clubs in New Zealand’s domestic system will ever see – and it creates a league with one rich club and a dozen paupers.

That disparity matters here too. Because while Liverpool will never be Auckland, the message is the same. Some clubs are being built into the framework. Others must fight for scraps.

Just because this tournament doesn’t stir the soul now – just because it feels synthetic, remote, or built for someone else – doesn’t mean it can be dismissed.

The Club World Cup is already shaping football’s future, whether supporters feel it or not. And if Liverpool aren’t in the room, they risk being seen less, followed less, and valued less – not for who they are, but for where they aren’t.

Absence doesn’t just mean missing a pointless tournament.

It means missing a platform that carries value in a very different way – commercially, culturally, and globally. This might not be the competition we grew up dreaming about. But it’s one that will shape who the next generation sees as elite.

And Liverpool need to be visible in that picture – not just to compete, but to define what football becomes next.

Fan Comments