Ian Rush‘s status as a Liverpool legend is without question, but his 15 years with the club sandwiched a strange and ultimately disappointing move to Juventus.

When Ian Rush returned to Liverpool, in the summer of 1988, he did so as a subtly different player compared to the one he was when he departed for Juventus 12 months earlier; when Rush returned to Liverpool, in the summer of 1988, it was to a team that played to a delicately different tune compared to the style they were playing when he left a year earlier.

Rush’s surprise availability for transfer, upon the eve of the 1988 Charity Shield, handed Kenny Dalglish and Liverpool a question they could have done without being posed.

On one hand, it was a transfer they could not refuse, while on the other, Rush was not a player that Liverpool needed.

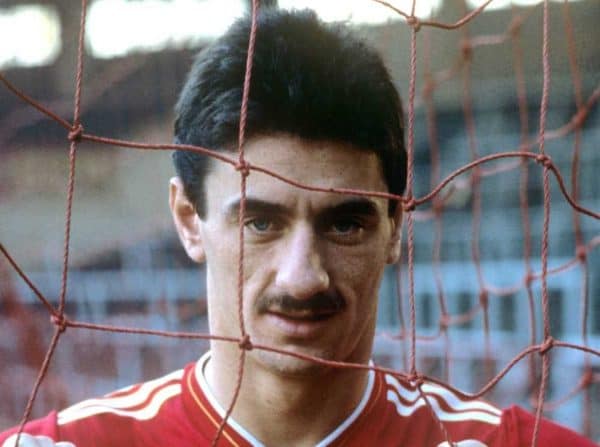

Prior to his move to Turin, Rush had been the deadliest striker in English football. For six consecutive seasons, he had scored vast quantities of goals as if it were his natural God-given right.

Within his first spell with the club, his lowest seasonal return of goals was 26, and the high-water mark was 47.

Swift of thought and feet, after a slow start to his career at Anfield, Rush began to thrive on a centrally driven ball for him to run on to, usually a run formulated from deep, where he would spin off the shoulder of the last defender or unassumingly drift in late.

In a crowded field of potent First Division strikers, the Liverpool No. 9 was unique.

Primed for the killer pass from Dalglish, Graeme Souness, Ronnie Whelan, Paul Walsh, John Wark or Jan Molby, Rush was something of an anomaly.

He wasn’t strictly a penalty box poacher in the way his lookalike – and perceived score-a-like – John Aldridge would prove to be. Rush instead glided in at the last moment, to torment defenders who already had too much on their plate.

What Rush could do, that seemed to be beyond so many others, was that he was better the longer he had possession of the ball.

This was against the usual laws of footballing physics. Too much thinking time was often the enemy of the common or garden goalscorer, as this was the grey area where indecision would have the chance ferment.

Conversely, Rush kept his cool in such situations, and if anything, the less time he had on the ball in front of goal the more awkward the finish was.

Mindbogglingly, for almost six years Rush scoring a goal came with a guarantee of Liverpool avoiding defeat. It was an incredible run that was ended at the 1987 League Cup final, against Arsenal.

By then, Rush was little more than a month away from completing his protracted move to Serie A, the last season of his first spell in a Liverpool shirt actually being one spent on loan from Juventus.

As early as the summer of 1984, Rush was being scoped by the great and the good of the top flight of Italian football.

Napoli, having signed Diego Maradona that year, had identified the Welshman as the man to convert the opportunities the diminutive Argentine could produce, yet they had broken the bank in signing the greatest player on the face of the planet.

Napoli were not alone, however. Talk was high that AS Roma, the team that Liverpool had just vanquished in the 1984 European Cup final, had approached the Anfield hierarchy wanting to secure if not Rush’s immediate services, then at least first refusal once he was made available.

League titles were won by Rush in 1981/82, 1982/83, 1983/84 and 1985/86, the last of those as part of a league and FA Cup double.

Four successive League Cup winners’ medals were claimed, between 1981 and 1984, while that European Cup glory in Rome came three years after Bob Paisley had omitted the former Chester City man from an expected place among the substitutes in Paris against Real Madrid.

That devastation in Paris, followed by being banished back to the reserves at the beginning of 1981/82, prompted a showdown between player and manager. Rush demanded a transfer, and in an act of brinksmanship, Paisley granted it.

With an arm around the shoulder and a sage word in his ear over the need to be more selfish in front of goal, Rush would never look back. His opportunity in the Liverpool first team came again, and when it did, he grasped it within a blizzard of goals.

Improving year on year, this was the Rush who departed for Turin in the summer of 1987, a year after signing for Juventus.

When his new employers had dared to suggest that he move to Italy in the summer of 1986, where he would have been farmed out to spend a season on loan at another Serie A club in order to acclimatise to the Italian game, Rush insisted upon one more year at Anfield instead.

In retrospect, while he scored goals aplenty in a Liverpool shirt in 1986/87, for Rush himself it might have been better had he taken up the option of heading to Serie A 12 months before he did.

Dalglish’s team suffered an uncharacteristic fade out in the title race, and it was a campaign in which they ended empty-handed.

As Rush headed off for a season of toil, in a Juventus side that struggled to cope in the wake of the retirement of Michel Platini and the loss to Internazionale of Giovanni Trapattoni, Liverpool regenerated impressively.

That is considering that the departure of their lethal marksman and the advancement towards retirement of Dalglish the player was perceived to be the end of the Anfield empire.

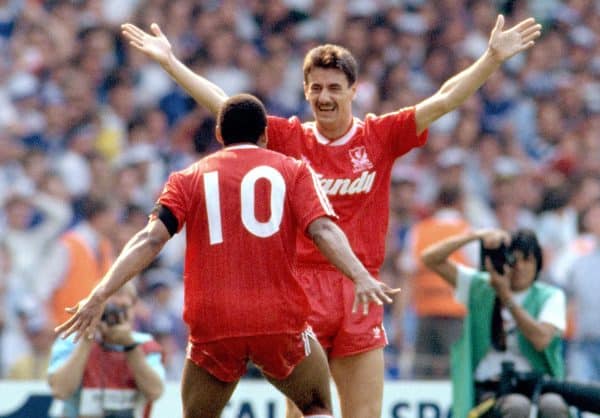

Aldridge was joined by John Barnes, Peter Beardsley and, before long, Ray Houghton. Added to this, Whelan was converted from left-sided midfielder to a central role alongside Steve McMahon.

These changes brought with them a different style of play. Suddenly, this was a Liverpool that used the wings far more than they had for well over a decade, and Aldridge was the perfect striker for the system.

Stereotypical penalty box poacher, Aldridge had an uncanny knack of being in the right place at the right time.

Swift of thought and feet, just as Rush had been, the new goal king of Liverpool instead thrived upon a ball played from wide positions or cut back from the by-line. Many of his goals came with just one touch, and he was prolific with his head in a way his predecessor wasn’t.

Thus when Rush returned to Liverpool, just a year beyond his exit, he subtly upset the chemistry of Dalglish’s new system.

Surprisingly never gelling with Beardsley, Rush did, however, link well with Barnes during his second coming.

The irony of his return to Anfield was that his arrival killed off the prospect of Paul Gascoigne becoming a Liverpool player – a man who would have provided the perfect centrally driven balls that Rush would have taken in his stride.

“Newcastle wanted £2.2 million for me. Liverpool were only going to pay £2 million because they were signing Rush back from Juventus,” Gascoigne once explained.

“So Kenny Dalglish said ‘can you wait another year?’. “I said, ‘I don’t know if I can.”

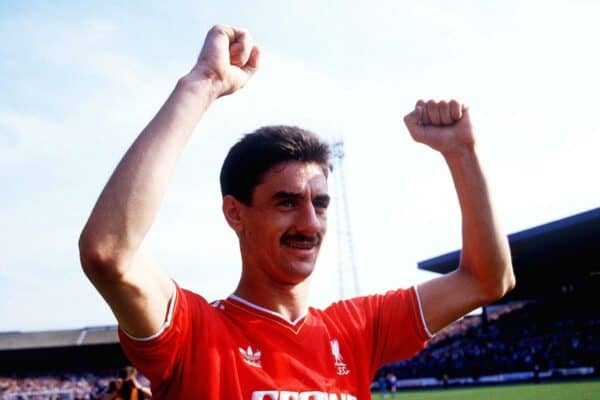

Eventually, Aldridge moved on, and another league title fell to Rush to go alongside two more FA Cups and a League Cup, yet he was never as comfortable a fit with Liverpool the second time around compared to how naturally he complemented them the first.

It wasn’t a problem that Rush returned to Liverpool, it was just a shame that the prodigal son’s stay in Italy didn’t stretch to another a season or two before he did come home.

Fan Comments