It has long been argued that politics should be separate from football, but the derisory chants aimed at fans of Liverpool and other clubs proves this wrong.

Politics and football don’t mix, apparently. Politics has nothing to do with football and football should have nothing to do with politics.

But, paraphrasing George Orwell: the opinion that football should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

In its early forms, football was regularly outlawed by the ruling classes as it promoted unruly behaviour among the peasants and later the working class.

Any large gathering of those not in power has always been treated with suspicion by those in power, and the old days of 25-a-side or more matches between various towns and villages were sometimes seen as problematic.

Then with the industrial revolution it became a pastime for workers to let off steam.

Factory owners realised this lifted the morale of their staff so actively encouraged it, setting up teams, finding areas for them to play and train regularly, and adopting rules devised by various schools and clubs.

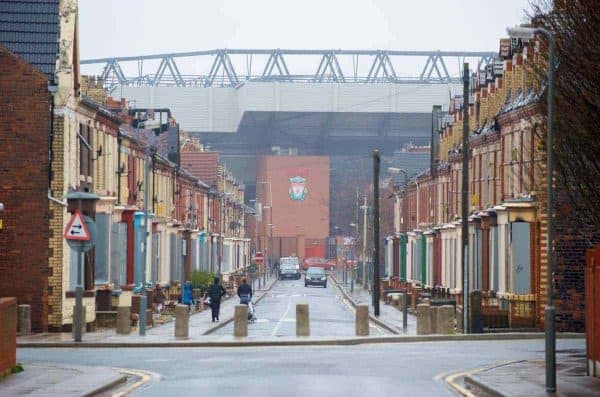

Football became a working-class sport.

‘Banter’

There is no avoiding the fact that throughout the history of the sport politics has regularly been present, and vice versa, especially in cities such as Liverpool.

However, it has gradually seeped into the stands under the guise of so-called “banter,” turning football fans who have a lot in common, beyond the colour of their shirt and crest on their chest, against each other.

Fans from various parts of the country are struggling as a result of a Conservative government’s austerity programme and then ridiculing each other at games because of it.

Liverpool has been the butt of such political jokes for some time now.

Its location as a port city and subsequent link to Manchester via the ship canal saw it become an area for the working class to sell their labour.

But in the late 20th century several things contributed to an increasing lack of jobs.

One was the introduction of new methods of working on the docks, specifically containerisation, which put many of the manual sorters who once littered the docks out of a job.

Manufacturing industries also suffered, and from the 1950s to the 1980s there was a steep decline in the city’s fortunes.

“Managed Decline”

Rather than support the changing nature of work in the area and generate new employment opportunities, Margaret Thatcher’s government left the city to rot.

The Toxteth riots in 1981 were the result of another tool used to turn the working class against each other: race.

It’s one still used to this day as Brexit continues to turn people of different backgrounds, but who have similar struggles, against one another. But it didn’t work in Liverpool—then or now.

The police’s unfair treatment of the city’s working-class people, particularly the long-established black population in Toxteth, prompted the riots as working-class people from all backgrounds came together in revolt.

The government used the riots as an excuse to send the city of Liverpool into a “managed decline.”

The then-chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, wrote to Thatcher, saying:

“We do not want to find ourselves concentrating all the limited cash that may have to be made available into Liverpool and having nothing left for possibly more promising areas such as the West Midlands or, even, the north-east.”

(The phrase “even the north-east” shows the regard with which they held that area of the country at the time.)

“It would be even more regrettable if some of the brighter ideas for renewing economic activity were to be sown only on relatively stony ground on the banks of the Mersey.

“I cannot help feeling that the option of managed decline is one which we should not forget altogether. We must not expend all our limited resources in trying to make water flow uphill.”

Choose Football – Targeting Fans

Shipments of drugs to the port led to good times and bad as those out of work sought escape through music and recreation.

Those who chose football as their drug of choice and form of escapism were also suffering.

Thatcher’s government repressed football fans across the country and sought to give them a bad name, but Liverpool were hit especially hard as a result of the general animosity towards the city from the government.

This came to a head in the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster, when Liverpool supporters were publicly blamed for the death of 96 fans.

It’s only recently that the truth, which many including those present at and affected by the disaster have spoken all along, is being more widely accepted.

The disaster was also a subject of jibes from opposition fans, and remains so to this day even now the truth is out there for all to read.

It’s yet another example of like-minded people being turned against each other by toxic, establishment-led media narratives which stick around like a bad smell, and are still peddled today.

“Always the victims, it’s never your fault.”

“Sign on, sign on… and you’ll never get a job.”

“It could be worse, you could be Scouse, eating rats in your council house.”

Those same fans who say ‘keep politics out of football’ then sing those above songs when visiting Anfield or when Liverpool visit their stadium. Ironic.

It’s not just Liverpool who are the subject of such chants and it applies to working-class areas across the country, but as recently revealed they are the most sung about team in the league.

Changing Times? Same Old Story

The oppression of the working class in the ’80s feels like it’s happening again under austerity.

Though this demographic takes a different form due to a change in the type of work and the places in which it is done, this class still exists and is still oppressed.

When capitalism inevitably breaks, as it has done throughout history and as Karl Marx predicted, those whose greed stretched the system to its limits and caused it to break in the first place aren’t the ones who pay for it.

This picking up of the pieces is forced onto those at the bottom, many of whom turn up at football grounds each week, forking out money for tickets and often club merchandise and refreshments, while also digging deeper into their pockets to give to charitable causes around the ground.

The communities around football clubs are doing their bit by supporting food banks, the existence of which has been attributed to austerity.

Liverpool and Everton contribute greatly to this cause.

It doesn't even make sense. (a) what's wrong with being unemployed or struggling for money? (b) why sing it at Liverpool when Newcastle has areas where it's struggling as well? We help the Foodbank, so why sing songs taking the p*ss about poverty? https://t.co/5n012ltVLQ

— Mark Douglas (@MsiDouglas) March 6, 2018

The city of Liverpool has paved its own path in recent decades thanks to the determination of its inhabitants to create successful businesses of their own.

Some help has arrived from the European Union, while local universities and colleges, businesses, football clubs and the communities in which they reside have seen something of a revival in the city.

Some now feel that the European Union has helped Liverpool much more than its own government have, with over 58 percent voting to remain in the EU in the ill-advised referendum.

This only adds to the detachment Liverpool has felt from the country in which it resides, and the feeling is echoed in a few other areas of the UK where football is a way of life.

They feel disillusioned with the whole affair, and despite there being left-wing reasons to leave the EU, Brexit has been adopted by the toxic right and is being botched by politicians at the whole country’s expense.

Football thrives when there is a level of animosity, tension and rivalry between opposing fans, but it can do without the self-defeating political point-scoring in the stands.

Working class supporters being priced out due to rising ticket prices and lower wages only dilutes the atmosphere. That’s politics affecting football.

Opposing fans not liking each other for 90 minutes is to be encouraged, and stadiums need an edge provided by the people within them, but beyond that it’s worth them recognising common aims and using this against opponents in the political sphere.

The game can be one of the greatest vehicles for people to come together to face problems inflicted on them from above and it has shown that throughout its existence.

There is evidence that the football community is coming together, but some sections of fans need to realise they are on the same team before this movement can begin to travel in the right direction on a larger scale.

Fan Comments