As the summer clearout continues at Liverpool, the club landed a major profit with the sale of Nigerian striker Taiwo Awoniyi to Union Berlin.

The 23-year-old, who arrived from the Imperial Soccer Academy in 2015 for £400,000, was moved on for £6.5 million after seven loan moves across three countries.

Awoniyi trained with the first team for the first week of pre-season in Austria, which was his longest exposure to the senior setup throughout his six years as a Liverpool player.

FSV Frankfurt, NEC Nijmegen, Royal Excel Mouscron, KAA Gent, back to Royal Excel Mouscron, Mainz, Union Berlin; from the age of 18, he was back and forth between Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium, with rare stops back in England.

There was more than a sense of inevitability in Awoniyi’s permanent switch to Union, along with a tinge of irony as it came in the summer that saw him finally eligible for a UK work permit.

When Liverpool confirmed the deal to sign the player in 2015, the announcement was accompanied by the news that he had been immediately farmed out to FSV Frankfurt – quite the challenge for a player moving from Nigeria to Europe, and it took him six months to make his debut for the German second-tier club.

To his credit, Awoniyi has worked tirelessly to build his reputation, with 34 goals scored and 16 assists made in his 139 appearances for various clubs since swapping the Imperial Soccer Academy for Liverpool.

But the role his long-time parent club played was, effectively, minimal, with the Reds merely serving as a conduit in his pathway to the Bundesliga.

For their part in the equation, Liverpool made a profit of £6.1 million; that is without factoring in loan fees paid by the clubs he called a temporary home over the past six years.

The word ‘home’ stuck out as Awoniyi savoured his permanent switch to Union, telling the club’s official website that: “After lots of loan moves in previous years, I want to finally come and have a home.”

It will have been difficult for the striker to fully apply himself as he joined the Liverpool squad in Saalfelden earlier this month, meeting many of his teammates and coaches for the first time, knowing that he was surplus to requirements.

Similarly, it would have been difficult for him and his wife on a personal level, having recently celebrated the birth of a son, not knowing where their next move would take them.

Profit vs. people

Awoniyi’s exit, after six years and seven loans, raises the question of player welfare and whether the Reds should be tangled in an admittedly lucrative approach to flipping overseas talent for profit.

Awoniyi is not the first player Liverpool have signed without securing a work permit in recent years, with Brazilian Allan Rodrigues’ £500,000 switch from Internacional very similar.

After impressing club scouts at the Frenz International Cup, Allan made the move from Brazil in the final months of Brendan Rodgers’ reign in 2015, his deal becoming official after time spent with both the first team and under-21s in pre-season.

Like Awoniyi, Allan was immediately shipped out on loan, joining Finnish side SJK on a short-term deal as an 18-year-old, followed by spells in Belgium, Germany, Cyprus and then back to Brazil.

The midfielder played only 57 times throughout loans with SJK, Sint-Truiden, Hertha Berlin, Apollon Limassol and Eintracht Frankfurt.

His return to Brazil with Fluminense, foreshadowing a permanent move to Atletico Mineiro, was a cathartic process for a player left “depressed” and “humiliated” by his experience in Europe.

“It was complicated, it was sad. The word was humiliation, which happened to me,” Allan was quoted in 2019, reflecting on his time at Eintracht Frankfurt, for whom he played four times.

“And that was discouraging me more and more to the point that I wanted to stop playing. I don’t know if the word humiliation is too strong, but there was not the human side, the understanding side.”

Allan added that “the desire was to stay at home every day,” with his difficulty in Germany leading to the early termination of his deal and a switch to Fluminense, facilitated by Liverpool’s loan pathways department.

When he eventually joined Atletico Mineiro at the start of 2020, the Reds made a profit of £2.7 million.

There were meetings with Jurgen Klopp in his early months with the club, but like Awoniyi, there was a slim chance he would have ever have played for them.

His depression was not directly caused by Liverpool’s treatment, of course, but it is certainly symptomatic of a player moving to a foreign country as a teenager and spending five years in temporary homes.

Next…

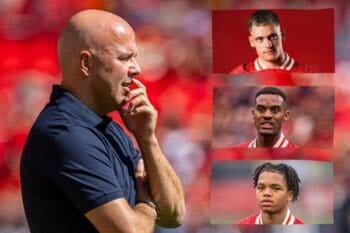

Awoniyi and Allan have now left the club, but there remains another example of this policy in Colombian full-back Anderson Arroyo.

The least-recognisable of the trio, Arroyo joined the Reds from Fortaleza in 2018, before being swiftly shipped out to Real Mallorca, where he spent half a season with their B side in the Spanish fifth tier.

From there, Arroyo has spent time with KAA Gent in Belgium, Mlada Boleslav in the Czech Republic and both Salamanca and, now, Mirandes in Spain.

His season-loan switch to Mirandes is yet to even be publicly acknowledged by the club, such is its importance.

It was only with Salamanca that the 21-year-old began to play regular first-team football, having served as an afterthought for all including his parent club for his first two-and-a-half years at Liverpool.

Arroyo’s peripheral role was perfectly summed up as Klopp struggled to recall the youngster when asked about him during a press conference on the pre-season tour of the US in 2019.

Arroyo is yet to qualify for a UK work permit, and though the post-Brexit rules may aid his prospect of securing one, in all likelihood he too will never play for the Reds.

Business sense?

Three players, signed from Nigeria, Brazil and Colombia as 18-year-olds, farmed out to clubs in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, Cyprus, Brazil, the Czech Republic and Spain before being sold on for a profit.

It may resemble a savvy business strategy for Liverpool, but there are justifiable questions over whether this is right, or even humane, to treat young people this way.

Naturally, it would be remiss to levy accusations of neglect at the club, and they are far from Chelsea levels when it comes to their use of the loan market.

But regardless of how often loan pathways managers Julian Ward and David Woodfine have been in contact with the trio over the years, something still doesn’t sit right.

Awoniyi, Allan and Arroyo will undoubtedly have been paid handsomely throughout their time with Liverpool, and there is no denying their profile has been boosted through association with the six-time European champions.

Furthermore, they are complicit in the process; they chose to join the club knowing the road to a UK work permit would be long and possibly painful.

Allan, for example, has described his time on the books at Anfield as a “good experience,” saying “from each country I took something and I’m more complete.”

But is there a point when a duty of care should come before profit, with a player’s desire for home more important than seven-figure sums in the bank?

Fan Comments