Football fanzines might not be as popular as they once were, but the desire to express footballing opinions is as strong as ever.

As a youngster who didn’t get to Anfield very often at all, matchday programmes were my souvenir of the occasion.

Once older and able to attend more regularly, the fanzine became more attractive. It was less corporate, more real and it felt like I was helping to keep something alive.

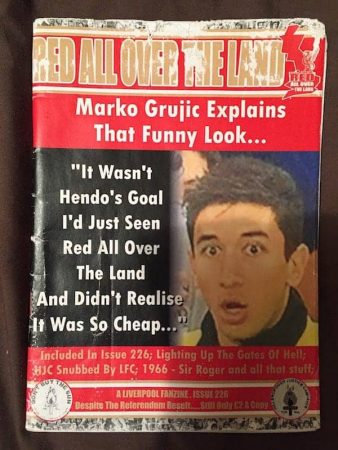

The club could do without my three to five pounds; two pounds for Red All Over The Land was much more reasonable – still somewhat of a memento but also actually readable.

A dying art form

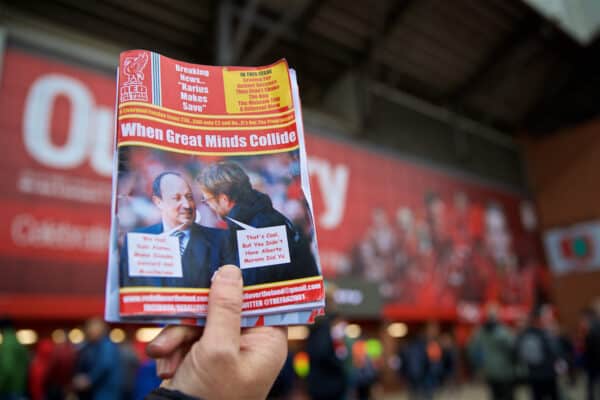

The football fanzine seller was once a staple sound of football grounds around the country. However, more and more clubs aren’t allowing them to be sold around club property and the fanzine is in decline.

Liverpool used to have several – Well Red, Another Wasted Corner, The Liverpool Way and Through the Wind and Rain, to name just a few – but Red All Over The Land is now the sole survivor.

Official programmes are more popular but even those have taken a hit due to the rise of the internet. It is here, on the world wide web of creativity, opinions and abuse that people are expressing themselves.

Instead of printing their ideas on paper, youngsters are publishing their thoughts online, sometimes garnering mass followings.

However, with the newfound ease of opinion-sharing, comes the ability to spout nonsense, hate and extreme views.

Radical viewpoints in the football world are obviously less of a problem than those that plague society, but that doesn’t stop the fact that discourse around the game has changed.

In the past, supporters would have to go to the trouble of printing their own publications at a cost, or submitting their work to fanzines already running.

It was much more difficult for attention seekers to spread their views to a wide audience, then. Now, though, with a click of a button, they can provoke masses of opposition supporters.

Shouting sells

Unfortunately, all this means that gaining notoriety through shouting down the lens of a camera, literally or metaphorically, is something that has become the norm in mainstream media.

Posting nonsense serves to rile up sensible fans and, in turn, they watch then reply. This earns the publisher money so they are incentivised to push the nonsense further and more frequently.

So much so that a certain radio station is now almost unlistenable.

Where has the voice of reason gone? Well, good sense doesn’t sell. This season, even the BBC and Sky Sports have started to bait supporters online.

The main PL broadcaster in the UK posting clickbait images for interactions. Football coverage in 2023. https://t.co/AzEZWUwapQ

— Ste Hoare (@stehoare) October 8, 2023

This is not to say fanzines are full of nuance and well-crafted balanced opinion pieces, that’s simply not always the case.

They cater for like-minded supporters and are bought by like-minded supporters. This does, though, mean they generally aren’t being absorbed by other clubs’ fanbases.

Fanzines aren’t created purely on the basis of making profit, unlike these internet caricatures you will no doubt scroll past after reading this article.

Fanzines are usually created out of love, creativity and passion for the team and supporters they serve.

Red All Over The Land’s founder, John Pearman, told This Is Anfield: “It took about six months to put everything together.

“It was done out of hours at work using a computer for the first time. I had access to all the little bits and pieces there, rightly or wrongly, but I’d use my position there to find time to do it.

“It was all put together with the usual things back then: Sellotape, Tipp-Ex, SprayMount, photocopying paper.”

Is there still an appetite?

Football isn’t less popular than before, despite what Florentino Perez might tell you, but print media is. So where are the thoughts and feelings of supporters being spread?

We’ve already mentioned the shouters and screamers, but what about those who are less driven by instant fame.

Liverpool supporters were at the forefront of the move to put content online. The website you’re reading this now on, This Is Anfield, has been going since 2001 and there are countless other webpages to absorb Liverpool content.

Multimedia has grown more recently than online press. The Redmen TV and The Anfield Wrap are two leaders in this field.

CEO of the latter, Neil Atkinson, said: “People like to hear authentically held, well-expressed opinions in an environment that actually promotes the idea that people are meant to enjoy this (football).”

It is this emphasis on enjoyment that guides The Anfield Wrap now. There are times to moan, but ultimately football is supposed to be a pass time. Mainstream media outlets riling up supporters doesn’t really fit this ethos.

Like the Wrap, a key element of fanzines is humour.

“We don’t make it sound as though it’s some sort of exhausting job. We make it feel as though this stuff should make it a joy to be alive,” Atkinson added.

Future of the fanzine

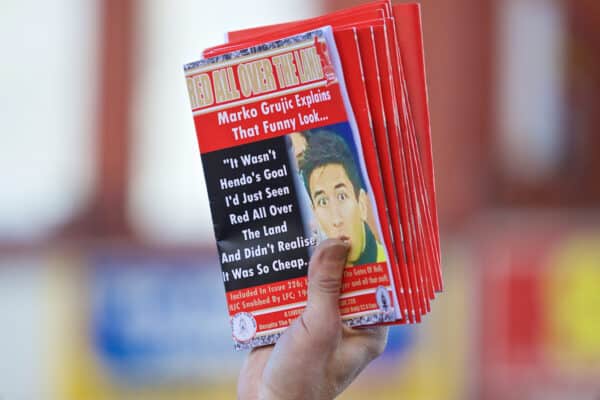

Regrettably, print fanzines are on the decline, and have been for some time, but there is still some appetite for them among match-going supporters.

Red All Over the Land is Liverpool’s last surviving fanzine from a once busy scene. Pearman believes there is still a market for them, despite the decline.

He told This Is Anfield: “People say it’s going out of fashion but I tend to disagree, because you can’t sell something digital to somebody who’s walking past – they want something in their hand.

“People want something in their hand, that’s how I see it.”

This idea of having a souvenir as well as piece of material to read is something journalist Elis James summed up eloquently.

He wrote in the Guardian: “The sheer passage of time turned these initially unremarkable documents into something spellbinding.

“I can see why some clubs have moved this stuff online. Printed programmes already appear as antiquated as the typewriters they were once written on.

“But, there are certain things you can’t do with an app.”

Fan Comments