The story of Tom Watson is a fascinating one, and the longest-serving manager in Liverpool FC history is next in our men who made Liverpool series.

IT’S a warm sunny afternoon in Liverpool, 1915. The May sun beats down on Anfield cemetery as a crowd of hundreds of mourners gather at a cool spot shaded by trees. On the ground over a hundred wreaths are laid, left there by the public, charitable organisations and the world of football. They include tributes from both Liverpool and Everton Football Clubs.

They had all been left there a for a man who had no enemies, who was admired by all who knew him, and whose coffin would be carried by the players he led to countless victories. This was the funeral of Tom Watson, Liverpool’s longest-serving manager, and this is his story.

The Liverpool Echo capture the event in sombre tones, on May 11th, 1915. Its article listed literally dozens of dignitaries and organisations who were present, and it is clear that there would have been a huge number of Liverpool supporters there too. This opening paragraph gives a glimpse of both the popularity of the man and the affection and admiration in which he was held by all in the game.

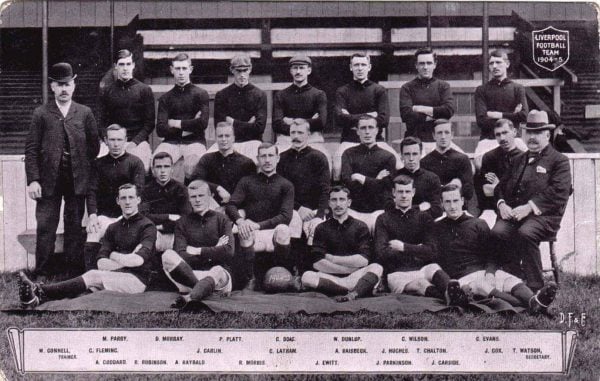

A cool corner of Anfield Cemetery had been chosen. The sun’s rays shaded his last resting place. “Tom” was buried there. The day was beauteously fine, and the setting of the last act was all peaceful. The whole sportsworld seemed to be represented. The late manager of the Liverpool Football Club had no enemies and the far-stretching reach of his works – charity being placed No. 1 – was in a measure shown by the representative gathering which attended to pay its last tribute to an esteemed man. The body was borne to its resting-place by old and famed players of the club: Raisbeck, Maurice Parry (in his regimentals), Charles Wilson, Goddard, Ted Doig, Bobbie Robinson, and Trainers Fleming and Connell. The following players of the past season were present: – J. Hewitt, T. Fairfoul, K. Campbell, A. Metcalf, D. McKinlay, J. Parkinson, J. Sheldon, R. Terriss, J. Scott, H. Lowe, E. Longworth, E. Scott, P. Bratley, M. McQueen, W. Connell, G. Patterson, and R. Riley.

When Liverpool Football Club persuaded Watson to become their secretary in 1896, he was already the most successful football manager in England, managing teams representing both the East and West ends of Newcastle, helping to found Newcastle Football Club at St James’ Park, before going on to lead Sunderland to three league titles.

His exploits in Wearside included back-to-back titles in 1892 and 1893 and three FA Cup semi-finals. His final championship for the Wearside club was secured in 1895, but by then he would have been the most sought-after man in football, and the Sunderland side he commanded were referred to as a “team of all the talents.”

With Liverpool promoted back to the First Division, the board were keen to show their ambition. So certain were they that Watson was the man to lead the club to glory, they would offer to double his salary, making him the highest-paid secretary in the league. He would earn £300 per year at Anfield, a huge sum in 1896.

Tom was more than a club secretary and arguably he was an early pioneer of the duties we most associate with club manager today. At the age of just 37, he had already become one of the greatest men in the history of the game of football.

This was the Victorian era, with Britain ensconced in colonial battles all around the world. The Boer War, which lasted until 1902 was just three years away. And, of course, a battle for a hill known as Spion Kop would eventually lend its name to the now-famous terrace on Walton Breck Road.

The motor car was in its infancy, and at the time of Tom’s arrival at Anfield, the law required that a man had to walk in front of cars, waving a red flag. That law wouldn’t be repealed until July that year. It would begin the glorious age of motorised transport.

Modernisation

At Anfield, modernisation was also on the agenda. With John McKenna (pictured above) now firmly back at the directors table, Tom Watson became more involved in recruitment, team selection and tactics.

A Journal called the Cricket and Football Field noted at the time, that Liverpool had never had a “[…]boss off the field and there have been too many on […]” hinting perhaps that the players were calling the shots. If this was the case, they would more than meet their match in Watson.

Liverpool’s new ‘manager’ was a believer in football science, understood the importance of diet and exercise – though some of his methods and ideas would raise eyebrows today – and was a powerful figure in the sport. He would have very quickly earned the respect of the dressing room. Whatever they were used to in the past, things were about to change dramatically and his impact would be huge, if not instant.

According to research by Arngrimur Baldursson and Kjell Hanssen and published on lfchistory.net the players’ day started early, with them reporting to Anfield at 07:30. Once there, they would complete a 30-minute stroll. It’s not clear where they would have done this, but it’s possible that locals would have seen them walking around the local neighbourhood or in Stanley Park.

Breakfast was served at 08:30 and would consist of ‘weak tea, chops, eggs, dry toast or stale bread.’ Tom did not want his players indulging in butter, sugar, potatoes or milk.

As in the modern game, training was split into two sessions, the first beginning at 09:45 and the last at 15:30. Watson allowed his players a glass of beer or claret for dinner and encouraged them to be sparing with their use of tobacco. The day would be a long one though, as they would end it with a stroll at 19:30, before presumably being told to get an early night.

It’s likely that these methods would have felt unusual, even arduous at the time. To convince players of the need to modify their diet and pay such attention to their physical wellbeing would have required a man with a huge personality and charisma. We must remember Association Football was in its relative infancy, and the days of kicking the ball around on parks and patches of wasteland would have been easily within the living memory of players and supporters.

Tom, therefore, was clearly a moderniser and very much associated with the professionalisation of the game. He may also have influenced the development of the game abroad too, though there is little documentary evidence of his activities overseas, this tantalising line in a Liverpool Echo tribute, written after his demise, is interesting:

“Mr. Watson was in the habit of spending his holiday abroad, and it is not too much to say that he had a distinct influence in popularising the game on the Continent.”

Recruitment techniques

Watson himself attributed much of his success as a manager to recruitment. In an article he wrote in 1899, entitled ‘Hunting for Men,’ and published in Leicester Chronicle, he gives an amusing account of the lengths football clubs went to in order to convince not only players to up sticks and move across the country, but also their families. Much of his early attempts to sign players took place in Scotland. However, he claimed to have no preference for Scottish players, pointing out that half his Liverpool team had their roots south of the border. He simply believed they were the best to found “at the time.”

When tracking a player, he would often have to employ cunning and subterfuge to outwit the secretaries of the clubs whose players he was ‘stealing.’ Success, he suggested, hinged on a number of factors, his friends and allies in Scotland, the owners of Liverpool, who were committed to financing the best football team in the land, and the club chaplain. The latter would be necessary to convince the parents of his targets that Liverpool FC had their sons’ moral and spiritual wellbeing at heart. However, they weren’t always successful in their pursuits, as his account here suggests:

“Sometimes our experiences were less edifying. The “chaplain” on one occasion had need of all his prayers for his own safety. It was in Glasgow, and we three had made our headquarters at a hotel there while hunting for a celebrated player. Our presence became known to his club, and a plot was laid to entrap us.

“The club secretary himself called at the hotel, pretending he was the player whom we wanted. He was rather shy of coming to close quarters; so we made an appointment to meet him the same night at a house in Govan-hill and settle terms. I thought it cruel hard lines that at the last moment I had a raging attack of toothache. It was a blessing in disguise. I escaped the unpleasant adventure of my two colleagues, who went without me.

“They were attacked in a low part of Glasgow by a mob of footballers, vowing vengeance on the “poachers”; ancient eggs flew right and left, likewise bags of yellow ochre, and more dangerous missiles still, and at last, they had to take refuge in a friendly doorway and knock for admission to the house. Here they passed an anxious time until the arrival of the police, who had been drawn to the spot by the row; half a sovereign rewarded their kindly host, and then, escorted by a large body of Glasgow police, they arrived back at the hotel, not without a parting salute of eggs and ochre from the disappointed mob.

“The ‘chaplain’, I must say, bore a very unclerical appearance. It was rumoured afterwards, at home, that I was the “chaplain” having disguised myself with his clothes; but, as I have said, I was saved – saved by the toothache, probably the only instance on record in which the toothache ever did anybody any good. I would go through it again under the same circumstances.”

The encounter with an angry mob in Glasgow seems to have altered Watson’s tactics, and they became even more devious as a result. He continues:

“After that, when in Glasgow, we adopted different tactics. Each of us stayed at a different hotel. The trick was simple enough, but it never failed to work at night. I would then call, in a cab, on my colleagues, pretend to take each of them up in turn, and drive off, followed by a crowd of angry Scots vowing vengeance on the English thieves who were stealing all their best players. When the enemy were out of sight the other two gentlemen set about business unmolested. I engaged the attention of the crowd till it was time to return and “CAPITAL BAGS, OLD MAN,” was the news that saluted me when I went to inquire next morning how the ruse had worked.”

Enter The Reds

Tom’s first game in charge of Liverpool was a momentous one in the club’s history, being the first game in which they wore red shirts and white shorts.

Therefore his arrival can be said to have also heralded the birth of a club that would later become known as ‘The Reds.’ The game was played away at Olive Green, against The Wednesday on September 1st, 1896. Liverpool triumphed 2-1 thanks to two goals by George Allen.

Watson led the Reds to a creditable fifth-place finish in his first season, the club’s first back in the big time. They had been promoted as champions of the Second Division the season before. However, it was Liverpool’s run to the semi-finals of the FA Cup that would have made supporters sit up and take notice.

Along the way, they had beaten a great West Bromwich Albion side, eliminated Nottingham Forest and took Aston Villa to a replay in the semis, eventually going out courtesy of a 3-0 defeat at Bramall Lane. Villa would go on to lift the cup, but Watson had more than justified his salary and his stewardship hinted at greater success to come.

The 1897/88 season saw a degree of regression though, despite Watson overseeing something of a revolution at Anfield. Five players would leave and an astonishing 17 men were signed for a combined outlay of £1295. It’s worth noting that with many fees unreported, the figure was likely to be much higher. Had there been any ‘net spend’ enthusiasts back then, they would have undoubtedly have been very happy!

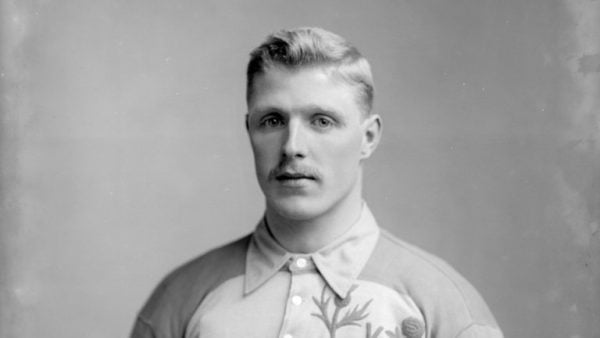

Liverpool were clearly an ambitious outfit at the end of the 19th century. They had recruited the best manager in the game, giving him carte blanche to build and shape the team as he saw fit and bankrolled him with huge sums of money. Their boldness in recruitment would pay dividends the following season, perhaps aided by the addition of a future club captain and legend, Alex Raisbeck, in May 1898.

Raisbeck appears to have been the final piece in the jigsaw for Watson and the team would come agonisingly close to winning the title in 1899, finishing second to Aston Villa after losing a title decider in the final game of the season. They would also once more reach the semi-final of the FA Cup, going out after an epic and titanic struggle with Sheffield United. The game went to two replays after matches ending 2-2 and 4-4. United eventually won 1-0 on March 30, 1899 at the Baseball Ground. Liverpool though were on the edge of glory.

In a characteristic of the Watson era, Liverpool once again regressed in the 1899/1900 season, slumping to 10th place and exiting the cup in the early rounds. It seems they were keeping their powder dry for another run at the title. And in 1901, with war raging in South Africa, and Winston Churchill making his maiden speech in Parliament, Anfield got ready to claim the first of many league titles.

Number 1

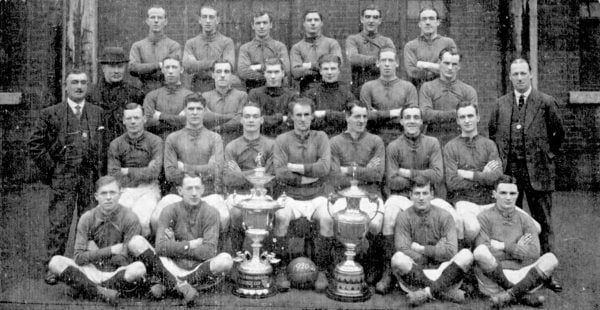

Watson would deliver the club’s first-ever First Division Championship on April 29, 1901. In doing so, he became the first man ever to lead two football clubs to a top-tier title.

He was now at the top of his game and Liverpool would have been the envy of every team in the land. Little wonder 60,000 people crammed into the space outside Liverpool Central Station way into the night, waiting for a glimpse of the newly crowned champions.

However, Liverpool’s fortunes would wax and wane in the early years of the 20th Century and the Reds suffered the ignominy of relegation in 1904. You can imagine the shock would have been palpable, and the board showed courage in keeping faith in their manager.

Their patience paid off as Watson led Liverpool back to the First Division at the first attempt. The stage was then set for him to claim Liverpool Football Club’s second top tier league title in 1906.

Watson was now the winner of five league titles as a manager, at two different clubs. His stock in the game could not have been higher.

However, it would reach the stratosphere in 1914, when Liverpool finally reached the final of the FA Cup. The achievement electrified the city and elevated the club’s reputation to elite status. Sadly, the Reds lost the game at Crystal Palace 1-0 to Burnley. But reaching the final and playing the game in front of the King would have captured the imagination of everyone on Merseyside.

We will never know what Tom Watson had planned for the next phase of his Reds evolution. He died in 1915 after a very short illness. He seems to have caught a chest infection and succumbed to pneumonia at his home in Priory Road, a short distance from Anfield.

He had been involved in team affairs just days before and the news would have stunned everyone associated with the club, and in the world of football. The Liverpool Echo wrote, in an article entitled, “‘OWD TOM’ WATSON DIES AT HIS HOME“:

Mr. Tom Watson – or “Owd Tom,” as he was familiarly and affectionately known throughout the whole football world – was perhaps the most popular figure in the Association code of professional football.

All who take any interest in the game know the exceptionally interesting history of the Liverpool club for the past seventeen years.

In that period it has had its ups and downs, but underlying all was a fine sense of sportsmanship that has overcome most difficulties, both financial and otherwise.

It was a popular saying that one never knew where Liverpool would be at the close of the season, for the club had a curious habit of finishing either close to the top or near to the bottom of the League competition.

The Anfielders, thanks in a large measure to Mr. Watson’s prescience, carried off the First League championship, the Second League championship, and the Lancashire League championship.

Like Paisley later, Watson never won the FA Cup. However, he was undoubtedly a hugely talented, respected and successful manager. He was just 56 at the time of his passing and had been planning a trip to the United States in the summer. The press would speculate that he may have been planning to advance the game of football in America, had he lived long enough.

Watson was Liverpool manager for an incredible 19 years and 742 games. He remains to this day, the club’s longest-serving manager.

He won two First Division Championships, the Second Division title and the Lancashire League. He also finished runner up in Liverpool’s first-ever FA Cup Final. He was a pioneer in his field and another one of the great men who made Liverpool.

The Men Who Made Liverpool

- ‘Honest’ John McKenna – The boy from Ireland who built an empire

- William Edward Barclay – The founding father whose life ended in tragedy

- Walter Wadsworth – Bootle’s fearless fighter, joker and skilful half-back

- George Patterson – The steady hand with an eye for talent

- Tom Bromilow – The superstar half-back they called an “artiste to the fingertips”

- Elisha Scott – The King who befriended the Kop

- Andrew Hannah, the ‘world champion’ who was LFC’s first captain

Fan Comments