Next in Jeff Goulding’s series of The Men Who Made Liverpool is Tom Bromilow, a player described as an “artiste,” and one of the club’s first superstars.

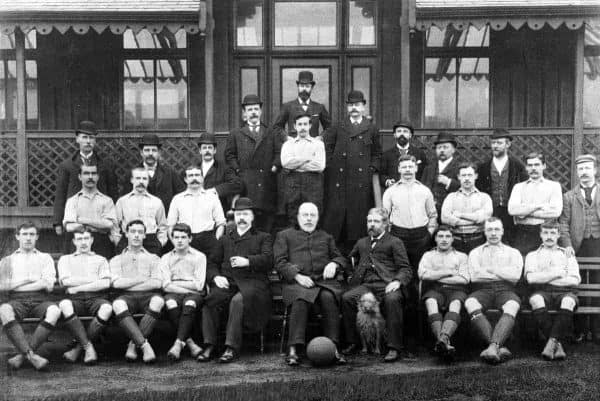

On October 13, 1894, Liverpool and Everton contested their first ever league derby at Goodison Park. The Anfield club lost the game 3-0 and by the end of the season they would finish bottom of the league. Liverpool would therefore taste relegation for the first time in their brief history.

However, less than a week before that fateful defeat and barely two miles from scene of battle, in the Kirkdale area, a couple called John and Alice Bromilow welcomed their seventh child into the world on October 7, 1894. They would name him George Thomas Bromilow. He would be considered one of the finest of his generation, ‘untouchable’, and he would win not one, but two championships with the Reds. This is his story.

Tom’s father was a blacksmith. In the Victorian era, wages for skilled craftsman like John Bromilow were double those of unskilled labourers. Therefore the family may well have been better off than some. However, with so many mouths to feed, life would have undoubtedly been challenging for them, and young Tom showed no signs of wanting to follow in his father’s footsteps. Tom loved football.

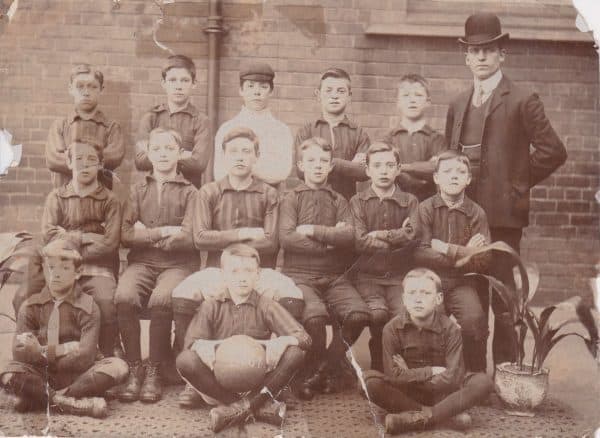

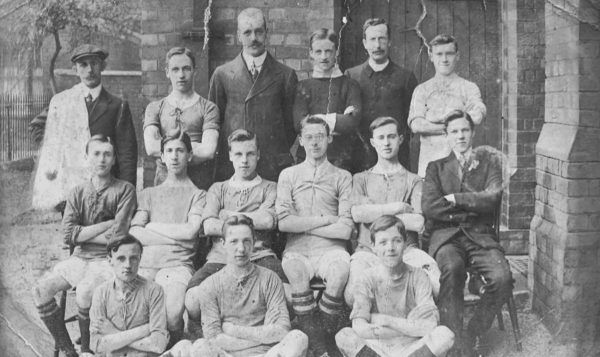

He had played for Fonthill Street Council School and later represented the Unity Presbytarian and West Dingle teams. However, the game offered little in the way of paid opportunities in the early 20th century, and by 1911, at the age of 16, he would take up a position as shipping clerk to one of many seafaring companies operating in the city. However, it is said that his passion for football got in the way of his job and he would soon leave it.

In 1914, Tom enlisted in the army along with many young men from Liverpool and served in the First World War. Details are sketchy on his service record, but great nephew Brian Spurgin believes he was part of the King’s Regiment Liverpool. Their depot was on Merseyside, in Seaforth, and they are known to have served on the Western Front, Salonika and the North Western Frontier. Of those who made up its ranks, more than 13,000 were known to have died in these campaigns.

Tom’s grandson, Lee Tracy, recalls a story passed down through the family of how Tom’s unit had been overrun by German troops, and he had needed to hide in order to evade capture. However, despite the perils of military service, it seems that the war and army life was to help cement football as Tom’s main passion, and his development as a player is often attributed to his service years. This passage from the Derby Telegraph on April 2, 1921, is typical:

“Tom Bromilow, the clever Liverpool and international half-back, graduated to Anfield by way of the Union Presbyterian FC and West Bathgate, though, like a good many present-day players it took a war and army football fully to develop his skill. He is a real Merseysider and the best of his career is that he did not cost the Liverpool club a penny.”

The last line refers to the astonishing story of how Bromilow came to be a Liverpool player in the first place. Upon the cessation of hostilities, and still an enlisted man, Tom literally walked into Anfield, knocked on the door, and asked for a trial. He was still in uniform. The club secretary, George Patterson, took one look at him and decided to give him a chance. He would go on to describe the future Liverpool and England half-back as “the luckiest signing I ever made.” He went on:

“His signature was obtained in the strangest manner. He came to the ground in uniform during the war and asked for a game. I asked George Fleming, who was in charge of the second team then, how he was fixed and he said he could do with another player, Bromilow played at outside right and was an instant success.”

He would sign as a professional as soon as he was demobilised, at the age of 25. He made his full debut on October 25, 1919, in a 2-1 victory over Burnley, a team he would later manage. He seems to have given a great account of himself, with a club programme later saying:

“Quite a good impression was created by the local lad Bromilow at right half-back; it was asking a great deal of him to place him against such a clever pair as Lindsay and Mosscrop, but he came out of the ordeal with distinct credit.”

James Lindsay was an experienced inside forward from Scotland. Eddie Mosscrop was an England international, born in Southport, who had the distinction of being part of the Burnley side who beat Liverpool in the 1914 FA Cup final. For Tom, with little experience as a pro, to face them and come out on top was quite an achievement. Writing later about his trial match for the Reds, the Athletic News had this to say on March 7, 1921:

“Bromilow is highly intelligent, and in the trial game showed, as always, power of anticipation and a rare gift in the bestowal of the ball. In no situation did he ever seem at a loss as to what he should do. There is a bright future for Bromilow.”

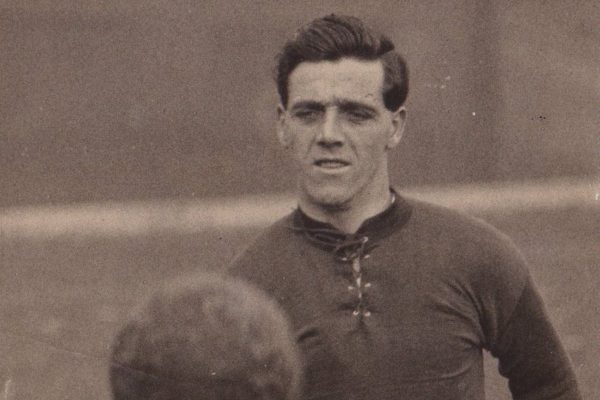

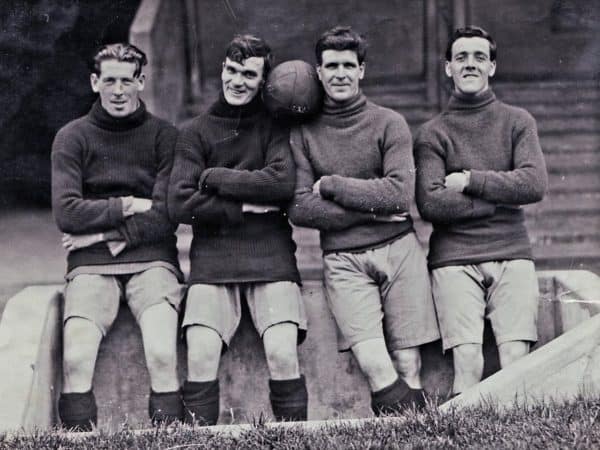

Throughout his career Bromilow played on both the right and left side of central defence, forming a formidable partnership with a fellow Scouser, Walter Wadsworth. But, at 5’9½” and weighing 11st 4lb, Tom would would rely on his footballing brain and guile to outwit opponents. Early reports of his performances paint a picture of a cultured centre-half who was great with the ball at his feet. However, the key was the partnership he struck up with Wadsworth, and how their contrasting styles complemented each other.

Consider this from the Athletic News in 1921, for example: “Wadsworth was a vigil destructive agent primarily, but in this game he also provided his forwards with repeated chances of forging ahead. Bromilow was more dainty in his methods but eminently efficient.”

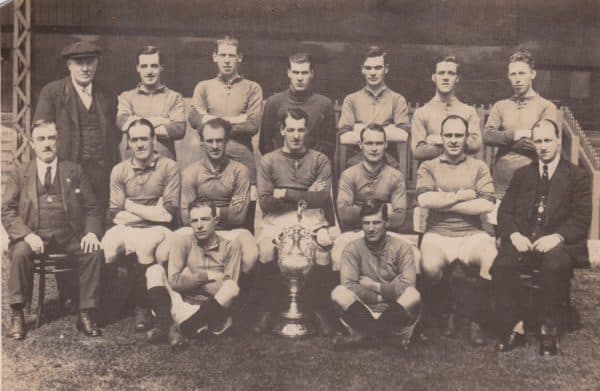

Tom, writing in the Topical Times in 1938, would describe Walter as a “bundle of muscle and bone. He gave and received knocks with a smile. Nothing disturbed him. He was a tremendous worker and a keen tackler.” These men were clearly friends and held each other in high regard, perhaps this was the key to their success. It was certainly a combination that served Liverpool well as they marauded to back-to-back league titles in 1922 and 1923.

In a season review, published in the Athletic News in 1922, the journal had this to say of Liverpool’s back line, which also included another player Tom held in high esteem, Jock McNab:

“The half-backs have presented contrasts, but they have all proved valuable in their different styles. The artist has been Tom Bromilow. It has been said repeatedly that team managers have found left half-backs the most difficult position on the field to fill to their satisfaction.

“That idea arrived before the famine in centre-forwards. We make no comparisons, but Bromilow is a player of the McWilliam type—that is to say, he achieves his purposes by footwork and the exercise of ingenuity.

“Walter Wadsworth is an intervener, a breaker-up of combination, with a more robust method. With Bamber stricken by appendicitis McNab has been most often seen at right half-back, and he has been very resolute. A footballer of his possibilities will probably become more refined.

“As a line these men have been very effective in their dual capacity.”

Indeed, throughout the 1920s, Bromilow is described as “artiste to the fingertips” and regarded as one of the most cultured defenders in the country. He was also referred to as one of the finest corner takers in the game. The Derby Telegraph wrote this of Tom in September 3, 1926:

“Yet another international, but just a dapper little fellow who has to rely purely upon craft and cunning for his success. [He] is purely Liverpool bred and born, and learned the game with such junior clubs as Union Presbyterians and West Dingle. His footwork in tackles is remarkable for the accurate timing he shows, while he is one of those halves who must feed his forwards after he has come out of a struggle with the opposition.”

Later, in another match report after a game against Portsmouth in 1928, they had the following to say:

“Though on the small side so far as weight and muscular strength are concerned, he is wonderfully effective and artistic in all he does. Has been in league football since 1919, and has reached international rank. No half could play the ball with greater effect.”

Tom had been a key member of the side that was regarded as the very best in English football. They would win the league title in back-to-back seasons in 1922 and 1923, earning the honorific, ‘Untouchables’. They were surely the pride of Merseyside and adored by the now legions of Liverpool supporters in the city.

Bromilow served Liverpool Football Club for 11 years and would captain the side during the 1928/29 season. Tom was clearly a pivotal player for the club during his time at Anfield. His contribution to the team is lauded in a Liverpool Echo retrospective, published in 2011. In it, Tom is described as the brains of the outfit, and there is more than a suggestion of his local superstar status. However, the regard in which he is held in the national press suggests his prominence and celebrity went much further than Merseyside.

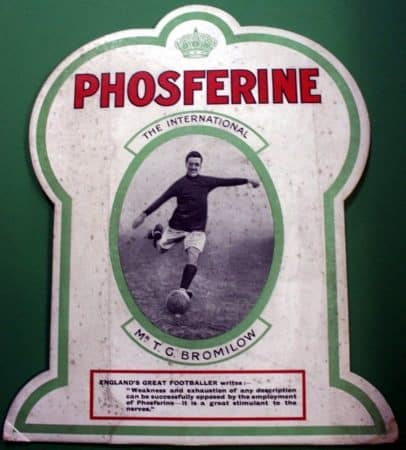

Off the field, Bromilow’s opinion was frequently sought on all manner of issues. He was a deep thinker about the game, something that marked him out for management later in his career. He was also something of a celebrity, having been sought out to do advertisements for health-related products, such as the mysteriously named Phosferine. One poster, dated 1920 and carrying a picture of Bromilow in action, featured this quote from the player:

“Weakness and exhaustion of any description can be successfully opposed by the employment of Phosferine – it is a great stimulant to the nerves.”

Not quite as catchy as Kevin Keegan’s Brut advert in the 1970s, or the Nivea adverts that feature Liverpool’s current crop, but perhaps we should rethink who we consider to be our first ‘superstar player’. It wasn’t just his image the media were after either, with the press regularly seeking out his thoughts on the game.

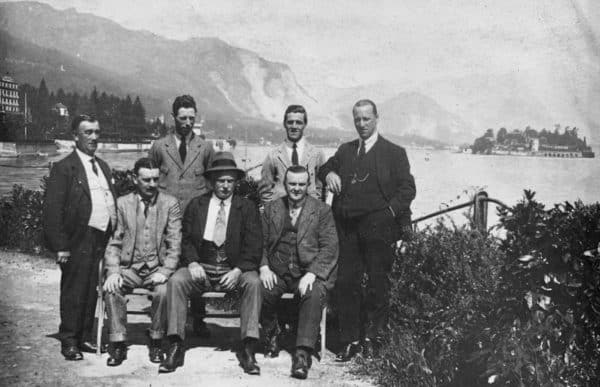

Tom wrote columns for newspapers during his playing days, including one while on a club tour in Italy. His views on the quality of the Italian game were far from flattering. In another, much later, he would call for the introduction of a second referee in games. It is little wonder that in 1927 the Rugby Advertiser would described him as “the deep thinking half-back of Liverpool.”

In trawling through the records and archived newspaper articles, we begin to get a picture of a footballer who was held in the highest regard in the English game. A man hugely popular among supporters and admired by reporters and fellow professionals alike. It is not hard to understand why. This is a local lad from modest beginnings, who served his country in wartime, and who played football at local and international level. Tom was capped five times for England.

However, it is only when you see family mementos and photographs from his private life that you begin to realise just how big a phenomenon Bromilow was. In discussing the life and times of this legend of the club’s past, This Is Anfield have been shown photographs of Tom’s wedding day. He would marry his girlfriend, Lillian Mabel (May) Kelly on June 20, 1923.

The Reds had just won the second of their back-to-back tiles, and by now Bromilow was a superstar. Amazingly, though, his address on the marriage certificate shows that he was living on Longmoor Lane in Fazakerley, an ordinary suburb of Liverpool, just four miles from Anfield and a short stroll to Aintree Racecourse.

Pictures of the happy day reveal scenes similar to those witnessed during the Beatlemania era of the 1960s. Hordes of people turned up outside the church, cramming pavements and any vantage point, desperate to catch a glimpse of the bride and groom. The streets leading up to the venue were lined on both sides, as if people were waiting to see a trophy paraded rather than the wedding of a footballer and his bride. So many people turned out to witness the event that the police struggled to control the throng. This was no ordinary footballer.

Alas, 1923 would prove to be the highpoint of his Liverpool career. The club went into decline after those incredible two seasons. Bromilow’s last appearance for the Reds came in a 1-0 defeat to Blackburn Rovers at Ewood Park in 1930. He was 36 years of age and the captaincy had passed to Tom Morrison.

Bromilow had many interests. He was a keen cricketer and enjoyed crown green bowling. However football was his true love, and after he hung up his boots he would head into management.

Not afraid of a challenge, Tom journeyed to the Netherlands, in order to learn his trade and perhaps gain new ideas about formations and training methods. He would spend two years as the coach of Amsterdam FC, before returning home to manage Burnley, where he stayed for three seasons.

Bromilow put his experiences to good use, transforming Burnley and revolutionising training. He was an avid student of football tactics—though his daughter, June, recalls that he pronounced it “tattics”—and drilled his squad regularly using table-top boards to outline his strategies. When he left for Crystal Palace, in 1935, the Burnley Express penned a very complimentary editorial by way of a farewell:

“Mr. Bromilow has been associated with the Burnley club for the past three seasons, and during that period he has done much to bring the town’s team once more to the forefront in football history. Only last season he had the distinction of seeing the team reach the semi-final of the English Cup, to be beaten in Birmingham by the ultimate winner, Sheffield Wednesday, and in his first season here the team went to the sixth round of the competition.

“During his stay he has introduced new training methods and more or less re-modelled the club. Of the players who were on Burnley’s books when he first came to Burnley only Cecil Smith remains.

“He secured the Burnley appointment in October 1932, out of 70 applicants, succeeding Mr. Albert Pickles, who had resigned. He had been coach to the Amsterdam FC for the season but, as the climatic conditions did not suit himself or his wife, he was anxious to return to England.”

Tom had two spells at Crystal Palace and also managed Newport County twice. However, his great disappointment was missing out on the Liverpool job in 1936. There were said to be 51 applicants and Tom was beaten to the post by George Kay, who went on to win the league for the club in 1947. His family say he was bitterly disappointed by that and had dreamed of managing his boyhood team. While Kay was clearly a success, there is a sense of what might have been, if that superstar defender had been given the chance to emulate his playing success in the dugout.

Bromilow would instead manage Leicester, but left them in 1945 after an apparent disagreement with the board. The Birmingham Daily Gazette reported: “Mr. Tom Bromilow, the Liverpool and England half-back and former Burnley and Crystal Palace manager, is terminating his appointment with Leicester City, owing to a disagreement with the directors over the future policy of the club.”

His final job in management came with his return to Newport County, where he spent four years before leaving in 1950. Somehow his difference with the Leicester hierarchy must have been healed, though, as he would finish his career as a scout for the club—a job he undertook until his death at the age of 65, in 1959. Tom passed away whilst on a scouting mission for Leicester. He was doing what he loved and still passionately involved in football.

His Anfield legacy is 375 games in a red shirt, 11 goals and two league titles. He was a Scouser born and bred who served his club with distinction. A lover and a scholar of the game and, above all, a Liverpudlian who delighted many thousands and lived the dream.

* Photographs courtesy of the Bromilow family.

Fan Comments