It has become an alarming situation for Liverpool in recent years, and here Dr Rajpal Brar explains why the squad picks up so many muscle injuries.

Liverpool’s season has been plagued by injuries – many of them muscular and many coming during training.

Those include Roberto Firmino‘s hamstring, Luis Diaz‘s knee, Thiago, Curtis Jones and Naby Keita on multiple occasions and, most recently, Stefan Bajcetic with an “absolutely bad” adductor injury that ended his season.

There’s little to no doubt the constant flux of players in and out of the lineup has led to inconsistency in play – a fact that Jurgen Klopp has reiterated multiple times throughout the season – and further compounded by those injuries coming to key, irreplaceable players in areas the club has yet to fully invest into.

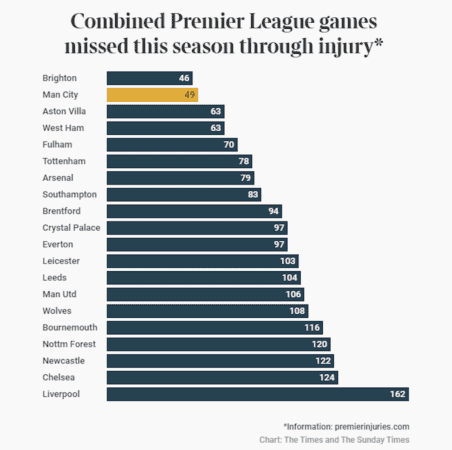

Additionally, Liverpool lead the Premier League in games missed through injury by a substantial amount.

* Graphic via the Times. Data accurate as of March 11.

The question becomes: what is causing these rampant injuries, specifically the muscular injuries, and why are more of them happening during training?

Let’s take a closer look.

An unprecedented season

First and foremost, this season is absolutely unprecedented due to a high-intensity international tournament being plopped right into the middle of it.

That change has created so many new variables and potential repercussions for players (whether they did or did not go to the World Cup) and clubs alike.

Liverpool’s coaching, medical, and sports science staff would have tried to account for those variables with changes to:

- Their fitness programming for players

- A training camp in December

- Certain benchmark metrics for players based on if they’re going to the World Cup or not

- Strategy for players returning from the World Cup in the short, medium and long term

However, there are simply too many new variables to account for and, although you do your best, whenever you have a massive change, there’s the possibility for massive repercussions.

One of those could be changes in fitness and injuries.

Fitness and injury risk assessment at the elite football stage is finely tuned and very sensitive, so when you throw a wrench into it – regardless of how well you’ve planned for it – it can lead to shockwaves.

Accumulated fatigue and wear

This iteration of Liverpool under Klopp has now been competing at a very high level for six-plus years, with a heavy reliance on certain players and playing in arguably the most intense league in the world.

Add in competing in the most intense competitions, and many of the club’s players being stalwarts for their international teams.

This naturally leads to a cumulation of fatigue and wear on the body, which doesn’t necessarily guarantee injury, but can shave the margins and increase injury risk.

For example, Virgil van Dijk recently gave an interview in which he matter-of-factly stated that he had played in too many games in recent seasons across club and country.

No other Liverpool player has come out and said that in public – although Jordan Henderson has multiple times criticised the Premier League‘s congested scheduling – but I’m confident if you took a private census, most would agree with Van Dijk.

Previous injury

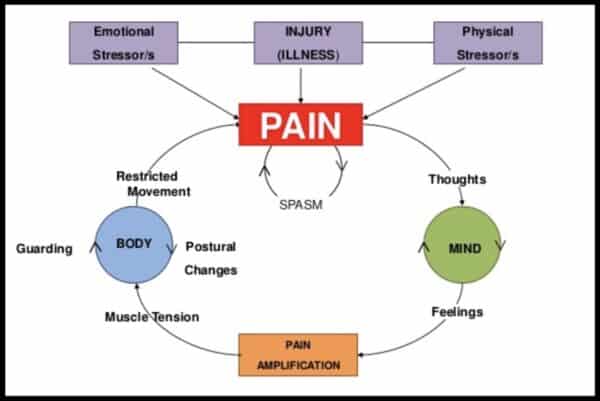

Once a player suffers a muscular injury, it is – by far – the greatest risk factor for that player suffering another muscular injury.

In Liverpool’s case, whether it be a player who picked up a muscular injury due to factors after they arrived at the club, or they came to the club with previous injuries, that player is now at increased risk.

A prime example of the latter is Thiago.

The sublime midfielder transferred to the club with a well-known injury history, having been through an ACL rupture and reconstruction and dealt with multiple muscular injuries.

He’s now at higher risk for muscular injuries, and when you combine that with the adaptation process to playing in the higher-intensity Premier League and a different style of play, that injury risk goes even higher.

Eventually, with enough injuries and inconsistent match play, it can become a vicious cycle where both previous injury and lack of fitness, along with potential changes to movement mechanics and poor confidence, combine to create a maelstrom of injury risk.

Keita and Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain are players who also come to mind here.

In the case of Van Dijk and Joe Gomez, who both dealt with serious knee injuries (the former a multi-ligament knee rupture and reconstruction, the latter arguably the worst injury for a footballer with a patellar tendon rupture), there’s also the risk for serious knock-on effects.

For example, this season Van Dijk picked up a hamstring injury, and it’s no surprise as the hamstring is a key supporter of the ACL (which he had surgically reconstructed) and often called the ‘surrogate ACL’.

These are just a few examples, but hopefully it paints the picture of how previous injuries and individual factors can really muddy the picture.

An inexact science

Keeping players physically and mentally healthy through proper strength and conditioning, nutrition and habits and sports-science testing, along with reducing injury risk through assessments and testing, is a key part of modern football.

But it’s still an inexact science.

One of my key pieces of advice for those aspiring to be in the medical world is that if you prefer black and white, it’s probably not the place for you.

Doubly so within the highly pressurised world of professional sports. There’s a lot we don’t know and so much grey area.

For example, The Athletic reported that there’s been some internal debate at Liverpool over the “boot camp” that Klopp likes to employ during pre-season.

He believes this helps them prepare for the demands of the season and be ready for it, whereas others think it could lead to physiological and mental burnout.

These debates and discussions may not be helped or be as cohesive currently due to some of the turnover in the Liverpool medical department.

Since 2020, first-team physios Jose Luis Rodriguez, Richie Partridge and Christopher Rohrbeck left.

Additionally, Jim Moxon, who was appointed as first-team medical doctor in 2020, left this past summer as well and his replacement, Jonathan Power, is yet to be seen.

Additionally, there are novel situations like players returning from the World Cup where it’s hard to know what is the right decision.

Do you allow a player who has been playing games and is match fit to rest and stay out of training, or do you want them to keep up with that fitness?

In Van Dijk’s case, it was decided he would take a week off from training and he recently said that he regrets that decision.

The fabled seventh season

Much has been made of the fact that Klopp’s tenures at Mainz and Borussia Dortmund floundered during his seventh season at the helm.

It’s easy to superficially conflate that with his seventh season at Liverpool but I haven’t seen any analysis on actual injuries at the three clubs during his tenure.

Bad luck

I’m rarely one to ever blame something on just luck, but there are cases with muscular injuries that are simply unfortunate.

Diogo Jota immediately comes to mind as he suffered a unique, rare calf injury from a mechanism that you rarely see in football.

There’s not much you can do about that and, unfortunately, he’s now at increased risk for injury to that same region.

Why during training?

Multiple of the club’s injuries have occurred or reoccurred during training this season, whether that’s Diaz re-injuring his knee and then requiring surgery, Keita picking up multiple issues, Jones struggling in training, Thiago picking up injuries in training and so on.

Why is a very hard question to answer without having much more detail (which we aren’t privy to).

For example, it could just simply be the nature of the injuries or that player’s injury history.

With Diaz’s injury, there was always a risk of re-injury during the ramp-up phase, especially in the latter parts of returning to full training.

With Jones, he was dealing with a very sensitive tibial stress injury (not overtly muscular but still ‘soft tissue’, so the same principle) that you have to stress during training but still be very proactive with.

In Keita and Thiago’s case – as discussed before – these are players with extensive injury history so they are at higher risk.

Additionally, based on some of the club’s recent injury struggles, there could be a change in methodology in terms of taking fewer risks with player health and how much pain or discomfort is acceptable for a player to train through.

This may appear on the surface as more players are getting injured in training, whereas in reality, it’s more due to a lower threshold for what’s considered an injury.

Last but not least, training principles have also steadily been changing – namely, training (and injury rehab as well) is becoming more intense to more closely replicate match fitness and prepare players for those demands.

Make no mistake, match fitness is never achievable without playing in games.

There are too many variables that you cannot replicate outside of a real, competitive game.

But this increase in intensity may be leading to more injuries in training as you’re getting closer to player capacity.

There’s a lot of complexity to the question of why Liverpool have picked up so many muscular injuries – and the answer likely stems over years – but I hope these reasons provide some sense of clarity and, at least, food for thought.

Fan Comments