Human cloning may be edging closer, depending on how successful scientists’ various experiments with animals are. It may prove more advanced at Anfield, if a coaching appointment proves successful.

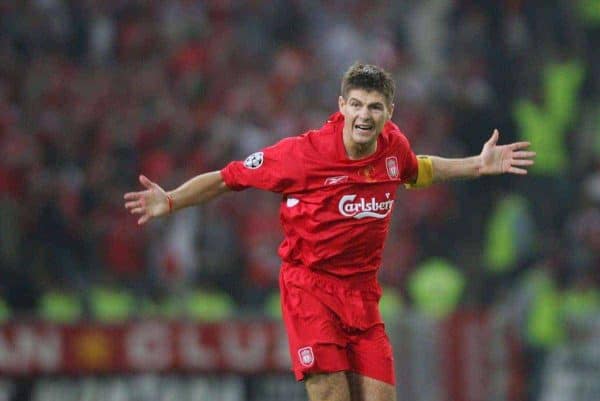

Liverpool will have a new Under-18 manager this season, one who seems to have given himself a particularly arduous task. Steven Gerrard, your job is to find, or create, the next Steven Gerrard.

Not that it has been phrased quite that way, either by Liverpool’s most iconic captain or the club. And not just because he remains the last player to come through the ranks at Anfield and become truly pivotal.

Yet the interview Gerrard gave when his appointment was confirmed in April was revealing.

“It is not just about tackles and competing. I hate watching footballers and football when there is no physical side and they don’t compete.

“There is a show-boating mentality throughout academies now and a lot of kids who play the game think they have to do 10 lollipops or Cruyff turns to stand out.

“We all love a bit of skill and talent but the other side of the game is huge, it is massive.”

— Gerrard

He spoke of a time before youngsters spent their time on computer games. He talked of wanting to see them snap into tackles. He presented a vision of football that remained as raw and primal as Gerrard could be. He sounded the academy coach with the anti-academy ethos.

Academies can have a tendency to churn out a type of product that can impress in a sanitised environment: neat and tidy, technically proficient but ultimately ineffective. Think of Tom Cleverley or Josh McEachran, and then think of Gerrard.

The Liverpudlian had more physical power, but the difference extended beyond that. Gerrard was England’s last great street footballer (Wayne Rooney, in this view, fell just short of greatness). He was coached expertly and eulogises Steve Heighway, Dave Shannon and Hughie McAuley for their influence when he was at a formative age, but he did not have the rough edges smoothed off by over-exposure to the professional world.

He could play on emotion. He did assume responsibility. His tours de force were about personality as much as ability. He was never focused on his pass-completion rate, always concerned about his impact. The propensity to go anywhere which seemed to frustrate the control freak in Rafa Benitez was the pure street footballer, but it often enabled Gerrard to be so catalytic.

He could dovetail with those who exhibited greater tactical discipline or who were reared to keep the ball, most notably in his alliance of opposites with Xabi Alonso, but Gerrard’s game always contained the impatience that he took from Huyton to Istanbul.

It seemed to make him a throwback. He certainly appeared more of an anomaly as Premier League clubs invested ever greater sums in academies and produced ever fewer first-team players. Some became profitable businesses, but perhaps part of the problem was that academies brought through too many academy-type players and too few with the Gerrard-esque capacity to make a difference that meant he had to play.

And while Gerrard may represent an outlier, simply because of how good he was, the reality is that his younger self would appear perfectly attuned to the times. The era of tiki-taka may be ending but the Spanish influence certainly contributed to English clubs believing they had to churn out midfielders whose sole concern was keeping the ball.

Now the historic strengths of the English game, its up-tempo approach, competitiveness and drama, have been harnessed by imports.

Even the Gerrard in the autumn of his career stunned Jurgen Klopp with his shooting prowess in his training sessions; the Gerrard of his peak would have suited the German’s heavy-metal football. A man Benitez rarely played in his preferred position might have even been granted the box-to-box central midfield role that Emre Can and Georginio Wijnaldum have shared last season.

It is easy to imagine the other foremost advocate of the pressing game, Mauricio Pochettino, savouring Gerrard; look at how he has fared with Dele Alli, perhaps the closest comparison among young Englishmen.

The 3-4-2-1 formation used so effectively by Pochettino, Antonio Conte and, of late, Arsene Wenger could have afforded multiple options to Gerrard, either to play at the heart of the side, shielded by three centre-backs and alongside a more defensive presence or roaming free further forward, Alli-style. An era of less tactical uniformity could have benefited one with his versatility.

If Jose Mourinho appears the antidote to ultra-modernity, the manager who defined the mid-2000s, it is worth remembering he admired Gerrard so much he tried to sign him for Chelsea in successive summers.

If Pep Guardiola was the personification of the Barcelona philosophy that then became the game’s governing philosophy, he Guardiola greeted Gerrard’s retirement by calling him “one of the best I’ve seen.”

While the Manchester City manager can be given to exaggeration, it seemed heartfelt. Getting the best out of Gerrard would have been a challenge to appeal to the Catalan.

The problem Gerrard’s new charges face is that most will never be remotely as good as he was. The difficulty for the fledgling manager is conjuring improvement from mere mortals.

Yet if Gerrard presented himself as an old-school figure, wanting hunger and commitment, aggressiveness and urgency, he was right to imply he needs to develop men for matches, not boys who just look good on the training ground.

To use an example from Everton, he needs more like Tom Davies and fewer like Tom Cleverley.

Too many academies have failed in part because they deliver too few bristling to make an impact on the pitch and coach the street footballer out of players.

The essence of Steven Gerrard never changed. As a manager, his challenge is to improve players while keeping the natural element that propelled him to greatness.

Fan Comments