John Barnes speaks eloquently about racism in the third part of our interview with the legendary Liverpool FC midfielder. We also reminisce about what some claim was the Reds’ most entertaining ever team.

Receiving racist abuse from opposition supporters (and sometimes your own), opposition players (and sometimes your own) was, and to an extent still is the lived experience of many black players.

At Liverpool in the ’70s, a young Howard Gayle, the club’s first black player, would experience degrading abuse from rival fans and, sadly, a team-mate. He wrote passionately about it in his book, 61 Minutes in Munich.

In his film, Poetry in Motion, John Barnes talks in an almost matter-of-fact way about his experiences of dealing with such a climate of hate. His former team-mates, like Viv Anderson and Mark Chamberlain, talk of how it drove them on and made them want to perform better.

For Barnes, though, there is a feeling that he has almost intellectualised his experiences, and that this has become his way of making sense of it and dealing with it.

Early in the film he describes the wonder-goal he scored against Brazil, at the Maracana Stadium in 1984. We are treated to archive footage of a young Barnes, dancing through the Brazil defence and dispatching a glorious finish into the net.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ystY7wR5lgY

It is a moment of sublime skill. To have done it against such illustrious opposition and in the home of Pele was surely one of the high points of his career.

Tackling racism

Barnes, though, is modest about it, choosing to play down the feat and emphasising that the game was a friendly. He then turns to the journey home. The England team flew club class, with many other ordinary passengers. He recalls two members of the far-right National Front sat on the same plane with their banners.

It must have been hard to take, for Barnes and his team-mates, to think that no matter what your achievements in life or the game, such bigotry is never far away. To make matters worse, nothing was said about this at the time. There were no complaints, headlines or inquests.

However, rather than speak angrily about these experiences, Barnes is measured.

“One of the issues I had,” he says calmly, “is that many of the people making a fuss about these things today, said nothing back then. For me, if it is wrong today, why wasn’t it wrong back then?”

His voice is calm and there’s no hint of bitterness, he simply reflects on the apparent contradiction in approaches over the years. I’m struck by how often I’ve heard Barnes talk about this issue, and I remark to him that he never seems emotional, or angry when discussing it.

“Not at all. The reason being that I understand it. It’s easy to be racist because of what we’ve wrongly been told about each other for the last 200 years. So you can’t blame racists.

“You have to look at the environment they’ve been brought up in. The culture they’re in, what they will have been told and learnt, and so therefore you look at society, and the solution to it is tackling that.

“You have to look at the cause of racism, not the symptom.”

“So, tackling the symptom is tackling John Terry or Dave Whelan or whatever little incident may happen. That’s the symptom. Until you tackle the cause, like any disease, you have to treat the cause not the symptom.

“And, the cause is what for the last 200 years, and I’m not just talking about in sport, I’m talking about society generally, what we have been told about certain people’s worthiness.

“After 200 years of indoctrination, it’s going to take more than 20 years of saying, ‘Oh, we’re all the same.’ So that’s what we have to do. Only through education can we get rid of it.”

Of course, many people from black and ethnic minority communities are justifiably angry about racism and discrimination, and quite rightly express that anger vocally and in the form of protest.

There are those that will point out the systemic nature of racism in society, of which education is just one component.

It is interesting, though, that Barnes appears able to almost put the emotion to one side when dealing with it, especially given his experiences. I ask him where that comes from.

Barnes talks about his experiences of a middle-class life in Jamaica and being aware of discrimination carried out against people, by others of the same colour. He continues:

“I tell you why I do that. Look at Africa and what goes on between groups who are the same colour. How can you discriminate against those who are the same colour? It’s because of what you have wrongly been told about those people.

“So, it’s understandable that in white society, you might feel a certain way about Indians; Chinese and black people because certain people tell you that.

“Black-on-black and white-on-black discrimination comes from a place where you have been misinformed about a group of people.”

Barnes’ insights are fascinating, and I can see that while he is no way attempting to minimise racism or discrimination, he feels passionately that understanding its origins is the key to eradicating it. We move on to Liverpool and his impact and experience of the culture.

Liverpool is a port city. As such, it played a significant role in the slave trade. Its legacy is that even today most of the ethnic communities in Liverpool live separately from the white population, who lived in the suburbs of the city. Although, thankfully, that is beginning to change.

I reflect on the fact that growing up, I knew only a couple of black families in my neighbourhood. I was also very aware of racist attitudes in school and on the Kop.

In the film, former lead singer of the local band The Farm, Peter Hooton, describes the demographics of the Kop in the pre-Barnes era. It’s a description I completely recognise; white, male and working-class.

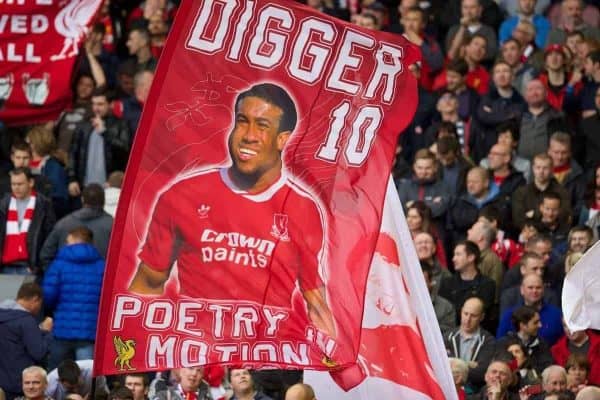

Liverpool supporter, Jag Singh Gill, talks movingly about his experiences of racial abuse and even violence associated with being near the ground as an Asian on matchdays. Today, he carries his banner, a tribute to John Barnes, proudly onto the Kop.

The image of the player, with the words ‘DIGGER 10 POETRY IN MOTION’ emblazoned on it and wafting in the breeze on the famous old terrace, is perhaps a symbol of how things have changed. Today, people of all backgrounds, religions and colours attend Anfield freely.

I wonder if Barnes is aware of the impact many feel he had on attitudes and the role he played in changing the culture. He is sceptical.

“That’s why I state it’s unconscious racism in football,” he explains. “Because I played well for Liverpool it may have changed, but if I came to Liverpool in 1987 and I was a terrible player, I don’t think it would have changed that much.

“I know black players who were abused because they were so-called ‘not as good’. So, that’s why it’s unrealistic if you talk about racism in football.

“If you give people what they want and you’re black, it’s like I got bananas thrown at me playing against Everton. If I played for Everton and scored a hat-trick, they would have cheered me.

“I got racist abuse from Liverpool fans when I played for Watford. It’s not personal. It’s why I say racism is not personal. It’s about the particular group of people you belong to.”

“If you look at Kevin Campbell, for example: they loved him. But, if you are Alex Nyarko, and they didn’t like him, then maybe he would get racist abuse from Everton fans.

“That’s why I’m more concerned about racism in society than football, because in football it’s unrealistic and unreal. That’s not what real racism is about.

“You know, what happens the other six days a week, when you’ve not got anything to do with football—that’s when you show your true colours.”

Liverpool’s greatest ever team?

The conversation has been absorbing and fascinating, but I realise we haven’t talked about his football, and in particular that unbelievable 1987/88 season.

I regale him with my experiences of following that team and how it was a joyous time to be a Red. I’d seen the great sides of the ’70s and early ’80s, but his was the most flamboyant side I’d ever witnessed. Surely, it was as joyous for him as it was for us.

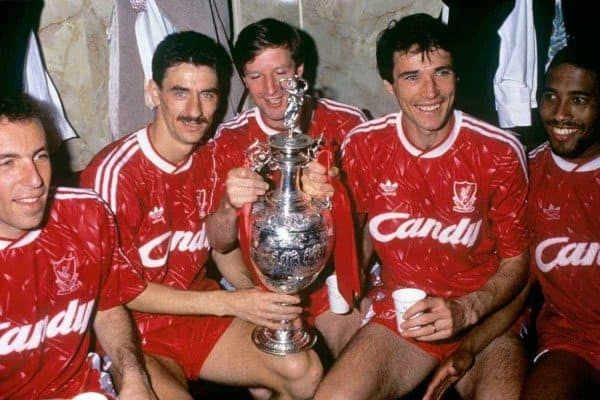

“It was. It just all came together after that first couple of weeks training. What Liverpool did, was they brought in Peter Beardsley, Ray Houghton and John Aldridge, all experienced international players. We came together when Rush and Dalglish weren’t there anymore.”

“So, we had to change the way we played, and Kenny has to take a lot of credit for that. Liverpool didn’t change things that drastically over the years. You had one or two coming in, but it was a complete change in the way we attacked.

“You bring one or two in a couple of years, but in one season we brought four in. They were the attacking players and how was that going to work, when you had to replace Rush and Dalglish.

“So Kenny has to take a lot of credit for having the foresight. He also integrated us into what Liverpool did. Liverpool did their homework into how players could fit in.”

There’s that theme again. Liverpool’s secret, if there was one, seems to lie in identifying a ‘Liverpool player’. He had to have game intelligence and be able to think for himself, be hardworking and adaptable.

Barnes may not have known it himself when he played at Watford, but he was the archetypal Liverpool player. The Reds’ hierarchy knew it, and so did Dalglish.

In the film, people like Jan Molby, Roy Evans and John Aldridge talk about his impact on that team. Up until he arrived, wingers were told to just get the ball into the box. It was the strikers’ job to find it.

Aldridge talked about how Barnes would invariably ping the ball to feet or head. It made the job of scoring goals so much easier.

Liverpool simply blew the league apart that season, finishing champions with weeks to spare and amassing 90 points. Defences wilted in the face of their relentless attack, and the Reds conceded just nine goals at home, scoring 49.

Their overall goal difference was +63, and they lost just twice.

They went 29 games unbeaten, equaling a record set by Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest. Sadly, it would be Everton who stopped them setting a new benchmark, with a 1-0 win at Goodison.

They’d also be denied another double, thanks to an inexplicable and freak defeat at the hands of Wimbledon in the 1988 FA Cup final.

However, none of that could detract from the fact that, in the 1987/88 season, Liverpool was the team that played the best football in the league, maybe the world. John Barnes was an integral part of that.

A conversation with John Barnes: Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four

* ‘John Barnes: Poetry in Motion’ is available on DVD, here.

Fan Comments