Jeff Goulding takes a look at the second half of 1988/89 in the concluding part of this two-part series.

As we bid farewell to 1988 and moved into 1989, January welcomed us with dreary warm and wet arms, Cliff Richard had been knocked from the top spot in the UK singles charts and was replaced with the equally cringe-worthy (from my point of view), Especially for You by Jason Donovan and Kylie Minogue, Amadeus premiered on the BBC, and Liverpool were preparing to travel to Old Trafford for an encounter with Alex Ferguson’s 9th-placed Manchester United.

Liverpool’s recent form against United would hardly have inspired confidence, and the news that Ian Rush would miss the game with a groin injury didn’t help either. John Aldridge for once had a poor game and would be described in one match report as “virtually anonymous.” What followed was the stuff of dreams for the home crowd and nightmares for the travelling red contingent.

After a first half in which Liverpool huffed and puffed but ultimately failed to blow United’s house down, the match exploded into life in the 70th minute.

With Peter Beardsley the provider, John Barnes opened the scoring for Liverpool and sent the away fans wild. The Guardian recorded the strike with little fanfare, suggesting that it merely angered United and “hastened Liverpool’s demise.” It’s difficult to argue, as, within seven minutes of going in front, the Reds were 3-1 down. The architect of this remarkable turnaround was a 20-year-old Russell Beardsmore, who had a hand in all of United’s goals and scored the third himself.

Liverpool were down and out and there was no way back in what was a miserable display. It was to be a tough trip back home to Merseyside for the travelling Kop. Dalglish’s side had slumped back into fifth place, United were just a point behind in sixth. More worryingly, though, they were now nine points behind Arsenal and Norwich who were vying for top spot.

Not champion quality

When I reflect on that season from a purely footballing perspective, something that is almost impossible to do given the long dark shadow cast over it by Hillsborough, my feelings inevitably centre on the gut-wrenching agony of surrendering the title to Arsenal in the dying moments of the last game of the season at Anfield, and on the ensuing pain and despair that accompanied that failure.

However, I realise now that from the perspective of January 1989, after that miserable defeat to United on New Year’s day, that the Reds had almost no right to be within seconds of a historic second league and cup double-double in the first place.

After 19 games, Liverpool had won seven, drawn seven and lost five. They had managed a little over a goal a game and were woefully inconsistent. Their league season should have been given a standing count.

Instead, a run of 11 wins and two draws from January to April saw Liverpool claim top spot in the table. They had tightened up at the back, the return of Bruce Grobbelaar from a long layoff due to illness, and Aldridge’s 10 goals in 13 games had dragged them to the summit on goal difference.

During this spell, the Reds had progressed with ease in the FA Cup, dispatching Carlisle and Millwall.

February saw the launch of Sky Television and the huge controversy surrounding the publication of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. Liverpool faced Hull City in the FA Cup fifth round at Boothferry Park. They took the lead through John Barnes but went in at halftime 2-1 down. A second-half brace from Aldridge saw them through and a home tie against Brentford was the reward.

Life felt good…

With Liverpool now genuine title contenders after a miserable start to the season, and within one game of another FA Cup semi-final, all seemed right with the world.

In Scotland, the introduction of the Poll Tax, a year earlier than in England, a huge campaign of non-payment was a mere precursor to what would follow in 1990 when the tax was rolled out south of the border. In Liverpool and around the country, communities watched the tactics of Scots non-payers with interest and continued to organise their streets and housing estates into “anti-poll tax unions.”

The Reds dispatched Brentford with ease with goals from Steve McMahon, Barnes and a brace from Beardsley. All that stood in the way of another trip to the capital was a semi-final clash with Nottingham Forest at Hillsborough.

With Liverpool now firing on all cylinders in the league, it looked increasingly like I might get my red victory on the football field, and with Thatcher’s grip on power looking increasingly precarious thanks to her ill-fated poll tax, that red victory on the streets seemed possible too. Life actually felt good, I remember.

The semi-final was set to take place on April 15, when an exodus of thousands of Liverpool fans would depart the city en-route to Sheffield, dreaming of glory and a place in the final. They would be joined by many more travelling from all parts of the UK.

The Bangles were number one in the singles charts, with Eternal Flame, a song that would grow in significance in the months ahead for Liverpool and their supporters. It was a glorious sunny spring day, perfect for football.

Turning down a ticket

Four days earlier, Liverpool had beaten Milwall 2-1 at The Den thanks to goals from Barnes and Aldridge. However, all eyes were now on the semi-final and inevitably the search for tickets. I desperately wanted to go, but cash was a huge issue for me at the time. I was unemployed and I knew that I probably couldn’t afford a semi-final outing and a trip to Wembley too. Still when the suggestion of a ticket being available came my way, the temptation to go for it was overwhelming.

I never asked whose ticket it was, the conversation went along the lines of so-and-so (I can’t remember the name) “reckons they can get you a ticket no problem, if you want one, face-value like. Do you want one?”

I agonised over it, knowing that if I didn’t make my mind up soon, it’d be gone anyway. In the end, I said no. I couldn’t afford it, I was skint. I have no idea who took the ticket, though I came close to asking a number of times since. I probably wouldn’t have known them personally anyway, I just hope that whoever it was, they got home safe and that they’re doing okay now.

A number of my mates did go, and again I am lucky in that I didn’t lose anyone at Hillsborough.

I can remember the day vividly, the build-up, the anticipation and the excitement. Then came a growing sense of horror as scenes on the telly showed images of crowds on the pitch and people being dragged from an awful crush on the central pens.

Overlayed on the imagery is the sound of the BBC reporter telling us (wrongly) how ticketless fans had forced their way into the ground and caused a crush, and my heart sunk. This was of course a horrendous lie started by Match Commander, Peter Duckenfield, and unwittingly spread through FA officials and media outlets, before the police admitted later that it was they who had opened the gates to the Leppings Lane end themselves, allowing fans to surge through and be funnelled directly into an unguarded tunnel leading to the already overcrowded central pen. The Taylor report and subsequent Hillsborough Independent Panel established that Liverpool fans played no part in the cause of the disaster.

I watched in amazement at first, then in utter horror. I had mates at the game. I couldn’t call them, there were no mobile phones in 1989. I wouldn’t know if they were safe or not for hours.

Horror and waiting

The game was now abandoned, and the scenes on television were growing ever more insane and incomprehensible. I was numb and decided to turn it off and go to see my then-girlfriend at her mother’s house. I think, as I left the house, I remember the voice on the telly saying that there had been fatalities. I couldn’t believe it. By the time I reached my destination the number of dead had already reached double figures.

We sat in silence, absorbing the news as it unfolded, unable to believe our eyes and ears. Then, the questions came flooding in, what about this person, or that person? Do you know what part of the ground they were in? Between us we knew several people at the game.

I would later find out that one mate, Les, ended up in hospital in Sheffield, he was safe but had been badly crushed and temporarily lost sensation down one side of his body. Physically he made a great recovery but I know he struggled with that day for many years after. We’re not in touch now, I hope he’s alright.

Another lad I knew, Billy, was in the pens. I don’t know which one, because he wouldn’t speak about it afterwards. I remember calling the information line the BBC had put up on the screen several times, only to encounter an engaged tone. Eventually, around midnight, I caved in to my anxiety and called his mum’s house number. I knew she’d be waiting for a call from her son, so had resisted potentially disappointing her with the sound of my voice, if she hadn’t heard from him yet.

When she answered the phone I could have cried, and I suspect she could have too. Her voice sounded weak, tired and faltering. She had picked up the receiver so quickly, it was obvious she had been sat by the phone waiting, hoping for a sign that her son was okay. “Oh, hiya, Jeff,” she said, clearly devastated, “no, I’ve not heard from Bill yet. I’ll tell him to call when he gets home. Thanks for calling, love.” I hung up quickly, feeling so guilty for troubling her and went to bed.

Billy phoned me the next day. He sounded different though, quiet where he used to speak loudly and enthusiastically, of so much so that I struggled to understand him. This time his voice was subdued and he would only say that he was “okay” and that he had made it home in the early hours of the morning. He wouldn’t talk about it at all after that, and I never pushed him. He eventually seemed to return to his old self and got a job down south. We would lose touch over the years, but I still wonder how he is doing now.

Another mate, Ste, made it out of the crush unharmed. However, two other lads, who were in different parts of the ground spent agonising moments looking for him on the pitch, expecting to find him lying injured or worse. They have since described their utter sense of joy and relief when they finally found him alive and seemingly without so much as a scratch on him.

Dark times

This was the darkest of times and it felt like the bottom of our world had fallen out. I attended Anfield in the days afterwards. It just seemed like the only place I wanted to be.

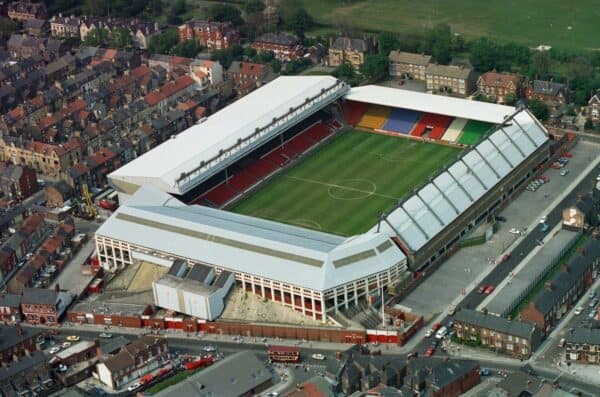

I’m not religious and the place had been like a cathedral to me my whole life. When I got there, it was like a shrine. The Shankly Gates were festooned with scarves, not just Liverpool ones, but Everton ones too, and the scarves and shirts of many other clubs. Messages of support and sympathy had been scrawled in black ink on many of them, and handwritten notes, poems had been attached to the railings.

Inside, the pitch was like nothing I had ever seen. The flowers, teddy bears and other assorted tributes had filled the goalmouth and were now creeping across the turf reaching the halfway line. We paraded silently around the edge of the playing surface in single file, taking in this huge outpouring of humanity and warmth and barely able to comprehend what we were seeing.

I remember Liverpool took some stick in some quarters for the way it mourned the disaster at the time, but years later this form of tribute was embraced after the death of Princess Diana. What had been described as “cloying sentimentality” by some, in the aftermath of Hillsborough was apparently okay for the death of a Royal. That people should be allowed to grieve however they see fit, free from the commentary of others, whether they are a football fan or a supporter of the aristocracy, shouldn’t be a controversial viewpoint. Seems it was in 1989.

I climbed onto the Kop and saw names scratched into the paintwork in the crowd barriers, it seemed like these were spots previously taken up by the lost and fallen, though I can’t be sure. Again, scarves were tied around the metal structures and notes and poems had been left on the steps. The tears flowed, but in those moments, it felt like we were not alone.

THE LIES

Then came an avalanche of lies and slurs. It hit us like a tonne of bricks and though I should have expected it, it was surprising to me both in terms of the scale of the deceit and the ferocity of it.

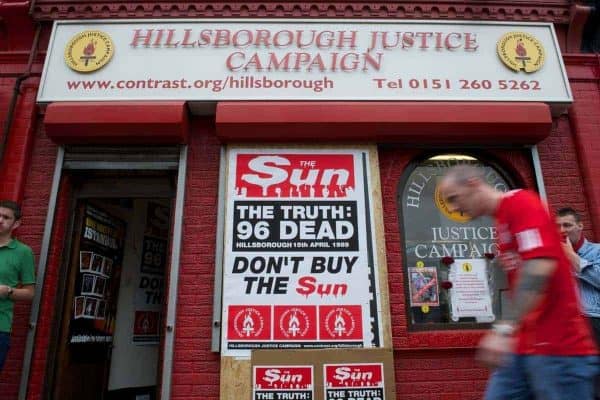

Many newspapers ran awful images on their front pages, of people fighting for their lives behind fences, their faces pressed against the steel, fighting for their lives. The s*n was not the only rag to repeat the lies cooked up by South Yorkshire Police and parrotted enthusiastically by Tory MPs, but it was by far the worse purveyor of sick smears.

Under the now infamous front-page banner headline, THE TRUTH, the paper falsely claimed that Liverpool fans had hindered police efforts to save stricken supporters, pickpocketed the dead and urinated on officers as they tried to resuscitate the injured and the dying.

Lurid claims of drunken fans forcing their way into the ground without tickets, and making lewd remarks about injured female supporters filled column inches and sadly too many people were taken in by it, despite the disaster being broadcast live on the nation’s screens and there being not a shred of video evidence to support these allegations.

The lies hurt us deeply, they continue to fester like a running sore to this day. Every time they are repeated by rival fans at a football match today, I’m struck by how easy it was for the establishment to switch the blame and focus attention away from their failings, and how despite numerous inquiries and reports placing the blame squarely on the police, how persistent and effective those lies were.

Aside from the personal hurt, the smears would do real damage to the campaign for truth and justice, and this was their most powerful effect. I have no doubt that justice and maybe even closure could have eventually been found, had the State simply held up its hands and accepted its responsibility. That was simply too much to expect of a pathological system hellbent on protecting itself at all costs, and I’m not sure much has changed since.

Football irrelevance

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, football seemed irrelevant. There was even talk of the season being cancelled, or at least the FA Cup.

Some speculated that Liverpool may play no further part. Nobody could have blamed the management, staff or players if they had simply decided that they no longer wanted to indulge in something as trivial as football. After all, they had spent the days and weeks after the tragedy attending funerals, visiting the injured in hospital and acting as grief counsellors without any training.

In an act of solidarity that will never be forgotten, the City of Glasgow opened its arms to Liverpool, and Celtic hosted a friendly match on April 30; 15 days after the events at Hillsborough. Many Liverpool players were said to be sceptical about playing, while some may have understandably been eager to try and get back to some sense of normality.

The game finished 4-0 to Liverpool, but the result was meaningless. What mattered is that the people of Glasgow had thrown their arms around Liverpool and that the players now believed they could go again.

The Reds resumed playing football and competed in both league and cup competitions. I don’t recall anybody I knew thinking it was wrong, though understandably some will have. I was glad they were going to carry on, but I don’t think my heart was truly in it.

Derby Thanks

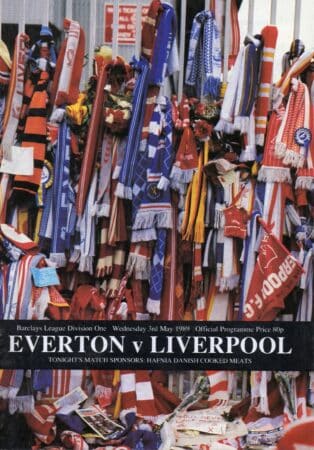

Fittingly, Liverpool’s first league game was a 0-0 draw against Everton at Goodison Park. This was a derby day like no other. There was none of the noise and raucous atmosphere in the pubs and streets before the game, going felt like a duty rather than the joyous occasion filled with excitement and nerves it usually was. The cover of the matchday programme simply showed a photo of the Shankly Gates adorned with red and blue scarves.

Liverpool supporters paraded a banner in front of the Everton supporters, which said “THE KOP THANKS YOU ALL. WE NEVER WALKED ALONE,” and it was received with huge applause by the Blues. The minutes’ silence was impeccably observed also.

For all the rancour and bitterness of today’s derby, there was none of that back then. Everton and their supporters were magnificent over Hillsborough, and for the overwhelming majority of them, they still are. Their solidarity as Scousers wasn’t unexpected then but it was a huge help. It continues to be so now.

The game finished 0-0 and, if it mattered to anyone, that meant that the destiny of the league title was no longer in Liverpool’s hands. The Reds were five points behind Arsenal with a game in hand. If the Gunners won all of their games, they would be champions whatever Liverpool did.

Four days later, Liverpool and Nottingham Forest would once again attempt to battle it out for a place in the FA Cup Final. The tie had now been moved to Old Trafford. Liverpool won the game 3-1, thanks to a brace from Aldridge and an own goal from Forest’s Brian Laws. That meant the Reds would meet Everton at Wembley, with another league and cup double at stake for the Reds.

In the run-up to the final, Liverpool retook top spot and were a point clear of Arsenal in second place, thanks to victories over Forest, Wimbledon and QPR. Their remaining two games were at Anfield, against West Ham, and the Gunners. The title was in our own hands again, but first there was an all-Merseyside FA Cup Final to take care of.

Wembley awaits

I had no desire to go to Wembley. Football had lost its joy and I couldn’t face the hunt for tickets and the journey down there. It just didn’t feel the same.

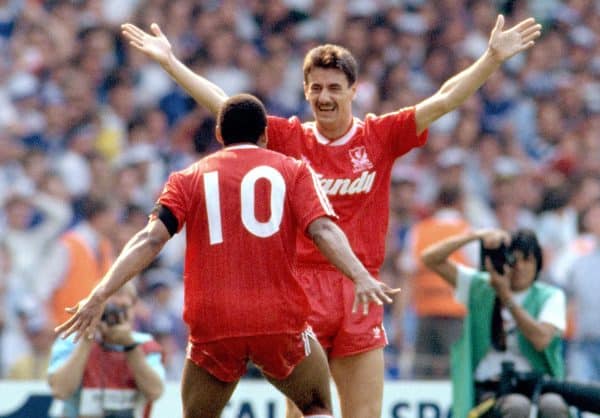

The houses in our road were still decked out in colours, as they always had been on cup final day. Some red, some blue, some half red and half blue. The game was a great one, and as it unfolded I could feel that old sense of excitement and nervousness returning. It was like a festival of football and the stands at Wembley looked amazing, a kaleidoscope of red and blue, just as they had in ’84 and ’86.

No one expected Everton to lie down, this was a derby after all, and there was a trophy on offer. I knew they would give us a game, and they duly obliged. In the end, the Reds emerged triumphant, winning the tie 3-2 after extra time. It felt great, and it felt right that we had played our neighbours in the final.

Now it was back to the small matter of the league campaign. West Ham were comfortably beaten 5-1 in a victory that put the Reds on the brink of the title. Goal difference was now a crucial factor though. Arsenal had drawn their game, which meant Liverpool were three points clear. If they avoided defeat, they would be champions. They could even lose 1-0 and still retain their crown.

The title decider

I was on the Kop that night and would witness the most painful defeat of my young life.

Arsenal took the lead in the 52nd minute, but with nails bitten down to the bone and nerves shredded, the Reds seemed to have hung on for a result that would seal a historic double, double.

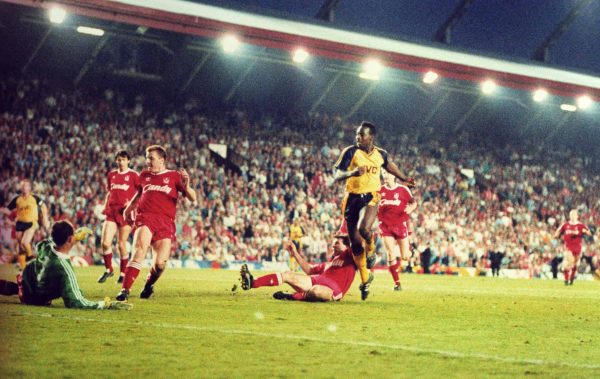

With seconds remaining, Michael Thomas – a future Red – would break my heart and those of every Liverpool fan, scoring a goal that would clinch the title for the Londoners at Anfield.

The pain felt immense, and tears rolled down my cheeks as I climbed the steps to the back of the Kop and left the ground. It wasn’t that I felt that we deserved to win the league or anything like that. It wasn’t even the last gasp nature of the loss, although that stung. I think it was more of a final straw, a last kick in the guts from a season that now seemed utterly bereft of even a meagre sliver of joy. Everyone associated with the club was suffering that night.

Steve McMahon would have this to say: “It hurts me. It hurts me. It hurts me so much. It was just unreal. It just flashed before you, the goal. It was like ‘Nah, is this really happening?”

The agony of that night and that game would eventually subside. Today it induces no more than a mild shudder and a half-smile, half-grimace whenever I recall it. It’s a story I tell my son.

However, the wounds left after the events of April 15, 1989 have never healed, they are as raw today as they have ever been. I’m reminded of that each time I read about or watch television programmes about Hillsborough, like the magnificent Anne. In those moments I am instantly transported back in time and the tears flow again.

For others of course, the pain is far worse. I have no idea how they endure it. They are an example to us all, the best of us. For them and us, 1989 will always be the season without end.

Justice for the 97, Justice for All.

Fan Comments