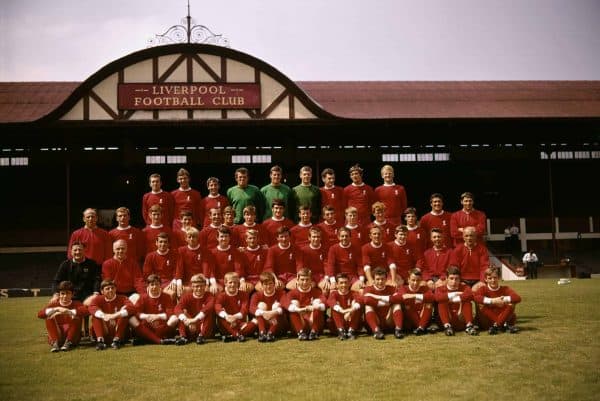

It was with an incredible sense of determination that Bill Shankly completed the signing of a 19-year-old Emlyn Hughes in February 1967.

It took a lot for a player to turn the head of the Liverpool manager enough to win himself a shirt on a Saturday afternoon at the expense of a current incumbent, yet Shankly was so smitten with Blackpool’s teenage talent that there would be no stopping the gravity of Hughes’ rise.

Shankly was enamoured with Hughes from the moment he saw him, and upon being given short shrift by Blackpool he would still phone the player every Sunday morning to proclaim that he would soon be heading to Anfield, and to check that the teenager was sufficiently looking after himself.

True to his word, Shankly swooped on Hughes as soon as Blackpool gave him the green light, a transfer that was partly facilitated by the man who had fought tooth and nail to fend off the advances of Liverpool.

Blackpool, amid an increasingly desperate relegation battle, parted company with their manager, and that man, Ron Suart, having been the main obstacle between Shankly obtaining Hughes, now became the conduit to the transfer.

It was Suart who swiftly advised the player that his career would be best served in the red of Liverpool, under the wing of Shankly.

Left back?

During the 1966/67 season, left-back had become an unexpected problem position, as Gerry Byrne suffered an accidental injury on the opening day of the defence of Liverpool’s league title at home to Leicester City.

From member of England’s World Cup-winning squad to picking up the injury that would eventually end his career before its time, Byrne was just a few days short of his 28th birthday and had many mountains still to conquer, yet he would play just 50 more games for the club before prematurely yielding to retirement.

In the absence of Shankly’s first-choice No. 3, Geoff Strong and Gordon Milne were asked to cover at left-back, with Strong adapting to the position well enough to eventually be handed the role on a regular basis, while hope remained that Byrne would overcome his injury.

Still, Shankly kept his options open, and when Hughes was signed it was largely perceived to be with left-back in mind – if not immediately, then certainly in the longer term.

Within days of Hughes’ arrival at Liverpool, he was unexpectedly thrown straight into first-team action at home to Stoke City. Not at left-back, but in midfield instead; alongside Willie Stevenson, in place of the injured Milne.

Liverpool were 2-1 winners, a result that returned them to the top of the First Division, yet after an FA Cup exit away to Everton – a game that Hughes was cup-tied for – Shankly’s side drifted to a fifth-placed finish, winning only two of their remaining 11 league games as the goals dried up.

Byrne had returned to fitness by the time of Hughes’ arrival, but would miss more games during Liverpool’s surprisingly lacklustre run-in. Across the span of these months, Hughes alternated between midfield and left-back, as Shankly sought the right chemistry for his faltering champions.

Valuable at left-back as Hughes was, Shankly was convinced that his new signing’s future was best laid in a more central position, from where the former Blackpool man could have a wider influence on the rest of the team.

Pivotally, Byrne was fit once again for the beginning of the 1967/68 season which meant Hughes could return to midfield, where he was emboldened by the departure of Milne to Blackpool and the dip in first-team prospects of Stevenson.

With Shankly answering his concerns over the previous season’s lack of goals with the signing of Tony Hateley from Chelsea, it meant that Ian St John dropped into midfield to partner Hughes, in a completely new pairing at the heart of the team.

St John’s eye for the angles combined with the boundless energy and commitment of Hughes, it was this partnership that effectively elongated the Anfield careers of so many of their team-mates.

Necessary change

It caused a domino effect that was to prove both a blessing and a curse, as Shankly delayed disbanding much of the team that brought Liverpool two league titles and a belated first FA Cup during the mid-1960s, along with the club’s first major European final.

Tantalisingly close misses were experienced in the title race during the 1967/68 and 1968/69 seasons, and it was the sense that his team were only a hair’s breadth away from new successes that stopped Shankly indulging in significant structural changes to his squad, apart from opting Hateley out and replacing him with the more aesthetically pleasing Alun Evans.

Even as the 1969/70 season began, apart from the occasional insistence of footballing gravity, Shankly was remaining loyal to many of his mid-1960s team, and he felt vindicated in his decision-making by an impressive start to the campaign.

Hughes was now the undisputed dynamo of Shankly’s team, and despite Byrne finally admitting defeat in his bid to play on, the Liverpool manager had no intention of switching Hughes to left-back, even with Alf Ramsey taking him to the 1970 World Cup primarily as a backup to Terry Cooper in the position.

Having not played a single minute in Mexico, between the autumn of 1970 and the spring of 1974 Hughes was to be England’s first choice left-back, Ramsey failing to follow the example set by Shankly in building his team around him in a more central position.

In the years to come, while England lurched from being outclassed by West Germany in the two-legged 1972 European Championship playoffs to failing to qualify for the 1974 World Cup with Hughes shackled to left-back, at Liverpool he was Shankly’s on-pitch general, dictating a new rise of a fresh team from the centre of midfield, joining forces with Ian Callaghan, who had switched from the right-hand side.

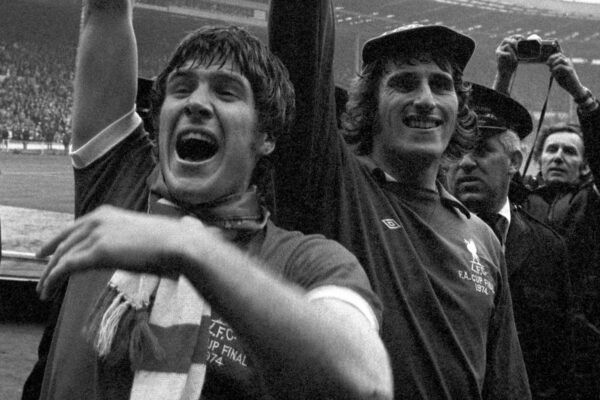

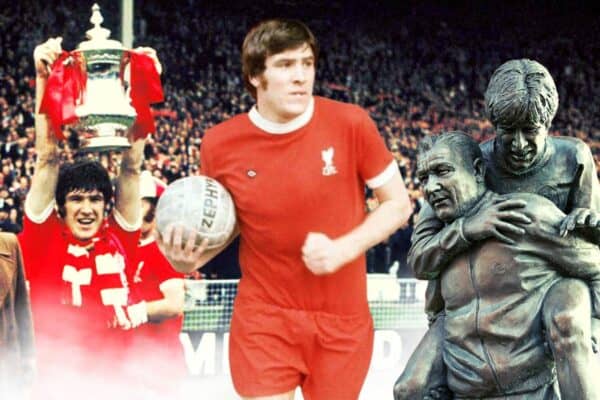

An FA Cup final was lost in 1971, while a league title was denied Liverpool the following season by a questionably disallowed goal late in the final game of their campaign away to Arsenal, but these disappointments simply spurred Shankly’s refreshed squad to greater heights as a league and UEFA Cup double was attained in 1972/73, followed by another FA Cup in 1974.

By the time of the latter of those successes, Hughes was the Liverpool captain.

Pioneers

In October 1973, Hughes was part of the England side that was held to a draw at Wembley by a motivated, talented but also fortuitous Poland, a result that sent the visitors onto the World Cup finals the following year. Again, Ramsey’s inflexibility was brought into question, inclusive of his lack of vision concerning Hughes.

At Anfield, by now Shankly had, too, begun to see Hughes’ future in a defensive role, yet not the one that Ramsey had handed him.

As part of the sweeping changes that Shankly had implemented at the beginning of the 1970s, the demise of Ron Yeats had been dealt with by the pairing of Tommy Smith and Larry Lloyd in central defence, who were covered by the adaptable Ian Ross, until the ambitious Scot departed Liverpool in search of guaranteed first-team football elsewhere.

Before the end of 1972, it had become patently clear that Ross’s replacement in the squad, Trevor Storton, was not of a high enough quality to be entrusted to be Liverpool’s primary backup central defender, and when Smith continued to suffer with a cluster of injuries during the autumn and winter of 1972/73 it was to Hughes that Shankly turned for cover.

Slotting in seamlessly, Hughes offered not only dependable cover but also a glimpse of Liverpool’s future, as he continued to venture forward with the ball at his feet, just as he would when in midfield.

A seed had been planted in the mind of Shankly.

Across those weeks, Hughes’ versatility shone, as he also covered a couple of games at left-back in the absence of Alec Lindsay, before returning to midfield, where he had been covered by the emerging Phil Thompson – Hughes’ future central defensive partner, but at that point a skilled, if physically awkward midfielder himself.

With Smith suspended for the formative games of the 1973/74 season, it was from here that Hughes’ move into central defence became an increasingly alluring prospect to Shankly.

With Callaghan enjoying life in central midfield, the impressive contributions of Thompson and the ease with which Peter Cormack switched to the centre from the right, while Hughes was irreplaceable in individual terms in midfield, his teammates collectively had it covered magnificently.

Smith was soon back in action, which meant a temporary return to midfield for Hughes, but when Liverpool made the trip to Highbury to face Arsenal in early November matters turned decisively.

Shankly stunningly omitted Smith from his starting lineup by choice, dropping Hughes back into central defence alongside Lloyd. The reaction of Smith was to storm out of Highbury and onto the first train out of Euston that was bound for Liverpool.

Three days later, Liverpool were knocked out of the European Cup at Anfield by Red Star Belgrade, Smith conspicuous by his absence even among the five-man list of substitutes, from where he would remain ostracised by Shankly for a further three weeks.

Anfield folklore insists that the Red Star game was the eureka moment where Shankly opted to restructure his central defence, switching traditional stoppers for ball-playing variants, yet it was an evolution that had already been 12 months in the making.

Smith would reclaim a place in the team, but it would not be in central defence, instead deployed to cover for the injured Chris Lawler at right-back, a position he would excel in for the best part of the next two-and-a-half years until Phil Neal took over.

Initially alongside Lloyd, Hughes went from strength to strength in central defence, before being paired with Thompson when Lloyd picked up a knee injury at the beginning of February.

Lloyd would never play for the club again, sold to Coventry City that summer for the biggest fee Liverpool had ever received. It was a shrewd piece of business.

Paisley’s evolution

Hughes’ partnership with Thompson blossomed to such an extent that they would link up together for England, as Ramsey’s two successors, Don Revie and Ron Greenwood, both called upon the duo, individually and as a pair.

Across the next five years, the trophies and the medals tumbled in Liverpool’s direction, as Hughes captained the club under Bob Paisley to three further league titles, two European Cups and one UEFA Cup, along with a handful of Charity Shields and a European Super Cup.

Liverpool’s new central defensive partnership, along with the expansive goalkeeping of Ray Clemence, was to be the triangular foundation upon which Paisley built a team that was as far detached from the traditional British style of play as could be possibly achieved.

A revolution of a system, one which was grounded in simplicity, Hughes lifted major European silverware in three successive seasons between 1975/76 and 1977/78, at a time when the club he captained was increasing its stranglehold on the domestic scene too.

Hughes was the on-pitch leader of Liverpool during unprecedented times.

Unwittingly, when Hughes lifted the European Cup into the Wembley night sky in May 1978, after the club defeated Club Brugge to become the first British team to retain the trophy, little did he or anyone else realise that he was soon to be a casualty of Paisley’s evolution policy.

There had been a certain irony that Hughes had been deployed for half of the 1977/78 campaign at left-back, covering for the injuries and dip in form of Joey Jones. Having been seen by many upon his arrival at Anfield as a left-back, it was in the autumn of his time with Liverpool that Hughesplayed most of his football for the club in that position.

What hastened the end of Hughes’ Liverpool career was the signing and hypnotically impressive ascent of Alan Hansen, whose composure and vision in possession was startlingly evident as soon as he made his first-team debut in September 1977.

Essentially Paisley’s fourth-choice central defender in 1977/78, Hansen was not to be restricted for long, and when he was paired alongside Thompson for the European Cup final the future had descended; by October 1978, Hansen had claimed the No. 6 shirt as his own, and with Alan Kennedy now ensconced at left-back, Hughes became the odd man out, despite remaining as club captain.

It was within the wake of defeat in the European Cup to Nottingham Forest that the tilting point occurred, as Paisley decided that Hughes could no longer fend off the challenge of Hansen, a fight that was now being hindered by an arthritic knee.

Crazy Horse

Hughes would sporadically return to action, usually at left-back as cover, or occasionally in place of an inconsistent Kennedy; he would play his last games for Liverpool in the two unsuccessful attempts to beat Manchester United in the 1979 FA Cup semi-final, occasions that came fast off the back of Hughes’ testimonial game against Borussia Monchengladbach.

On the eve of the 1979/80 season, Hughes was allowed to depart Liverpool for Wolverhampton Wanderers, where he would go on to lift the League Cup as captain – the one domestic honour that had eluded him at Anfield – even going on to gain a recall to the England squad for the 1980 European Championship, where just like in Mexico a decade earlier, he would miss out on an on-pitch contribution.

Beyond his time at Molineux, Hughes would make one last competitive return to Anfield, as the player-manager of Rotherham United in a November 1982 League Cup tie, in which the visitors restricted Liverpool to a narrow win.

Christened as Crazy Horse by the Kop – a nickname reputedly dreamed up by Evertonians in less complimentary origins – Hughes was widely adored by Liverpool supporters, but often struck a polarising figure in the dressing room, harbouring a long-heralded feud with Smith.

He was also said to have had further strained relationships with other team-mates too, while his political leanings were later brought into question by many.

After walking away from football management, Hughes moved into radio, television and print media, also gaining huge popularity for his appearances on A Question of Sport. He was on commentary duties for BBC radio at Hillsborough.

Hughes remained a regular voice on all matters Liverpool throughout the 1990s, and into the early years of the new Millennium, until his health began to suffer, finally succumbing in November 2004 to a brain tumour, aged only 57.

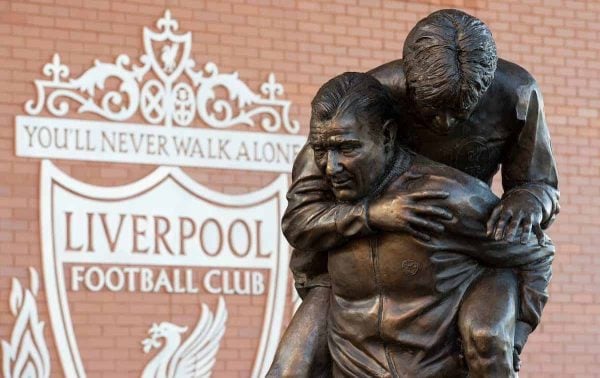

One of the most important players in Liverpool’s history, Hughes is immortalised at Anfield as part of a bronze statue of Paisley that was unveiled in January 2020, the player carried on the back of his future manager.

It is an apt image of two men giving their all for a club that they helped become the world’s greatest.

Fan Comments