The moral considerations that football ownership brings has been firmly in the spotlight and as Liverpool’s owners open the door to new investors, fans will be asked how much they are willing to compromise, writes Andrew Ramsay.

It’s matchday. The time is almost upon us.

Nerves. Excitement. Anticipation.

They all start to set in as we travel to the stadium. It’s an evening kick-off and daylight has already dissipated. The night-time sky covers the city in a comforting blanket of darkness.

As time moves forward and gets closer to kick-off the anticipation builds. Spectators sit down wound up like spring coils, their nervous energy creating a tension which sees them involuntarily spring out of their seats throughout the match at any given moment.

A wall of sound booms out from the impassioned voices and all begin to sing in unison. There is an unspoken understanding here of what is an undoubtedly unified cause.

Strangers in the stands catch each other’s eyes knowing they too feel the same emotions following their team. They understand the elation felt when winning. They understand the despondency felt when losing.

And, above all, they understand that a non-negotiable relationship – in sickness and health, if you will – means they have little control over how their team makes them feel.

Life and death

Supporting a football team is odd when you think about it. Most fans will be able to relate to this matchday tradition. Yet, paradoxically, it is exactly these traditions and loyalty to their own club which create divisions.

The reason?

In its essence, football, or any other sport for that matter, taps into a fundamentally tribal part of human nature. The need to belong to a group, have our feelings validated and know that we are understood is so strong that something so relatable can also become something so divisive.

A compelling argument can be made that it is exactly this tribalism which makes football what it is. Indeed, without it, it certainly feels like there would be far less at stake. The emotion which drives the winning and losing feeling would somehow become diluted in its absence.

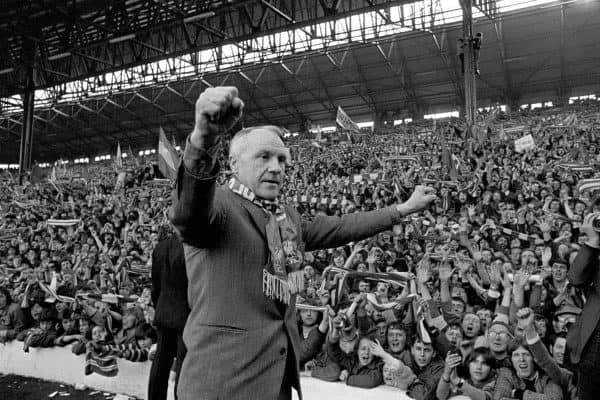

The great Bill Shankly once said:

“Some people say football is a matter of life and death. I can assure you, that is much more serious than that.”

Shankly’s sardonic humour, however, was tempered with a serious side. He was a man that was not only passionate about football and winning, but a man with a strong social conscious. In short, he was also a man of politics.

And this was embedded in his vision for the team. A long-term advocate of socialism, the collective was very much seen as a blueprint for his Liverpool side’s success:

“The socialism I believe in is everybody working for the same goal and everybody having a share in the rewards. That’s how I see football, that’s how I see life.”

Over the years there has been a strange tendency amongst certain fans and pundits to argue that football and politics are completely unrelated. Robbie Savage, is one of the biggest culprits of this during radio phone-ins, regularly retorting to any fan who expresses a political viewpoint, with comments like:

“Football has nothing to do with politics,” and “we need to keep politics out of football.”

There is certainly something appealing in this idea. For many people sport is a relief from the grind of everyday life. It provides a means of escapism.

Yet, to claim that it doesn’t exist within football at all is akin to saying, “I don’t like thinking about politics, so I just assume it doesn’t make any difference anyway.”

The genius of sportswashing

When news broke of Roman Abramovich’s assets being frozen by the UK government in April, in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the Chelsea owner’s relationship with Vladimir Putin, a seismic moment exploded into the consciousness of everyone with an interest in the Premier League.

A moment, which make no mistake about it, made a mockery of the notion that football has nothing to do with politics. If it is not related at all, then it mattered little how Abramovich made his money.

In reality, passivity fosters sports washing. Apathy allows moral corruption to grow. It also creates a useful facade, where people not only avoid questioning the integrity of someone’s actions but even go as far as complimenting them on their virtuous standards.

‘Abramovich was doing it all for the love of the game. He did wonderful things for the local community’, it was often said.

But therein lies the genius of sportswashing. One first becomes the figurehead of a highly visible and public sports company. One then ‘selflessly’ invests large swathes of their own money to take the club to dizzy heights that supporters could have never dreamt of previously.

One continues this cycle of investment and builds a strong association of success in their name. All done while establishing a loyal group of supporters who become accustomed to a certain standard of football team, a team which continuously wins trophies.

Lessons learned

A serious conversation about ownership in football needs to happen. Those who think football and politics are not related are living in fantasy land. Especially football in its current form.

Wealthy associates of foreign states buying into football has become increasingly common, and as the already astronomical amounts of money in the game increase and foreign entities attempt to establish more geopolitical power and influence, there is a moral imperative to undertake due diligence and consider the implications of any investment.

But will the Premier League seriously consider any regulatory changes?

If the Abramovich saga had been a fictional Netflix drama, the scriptwriters couldn’t have come up with a better plot twist; a moment in the story where conflict is thrust upon the audience; a state of cognitive dissonance is established, and the viewer must think about the relevance of what they have they have just witnessed.

The same week that Abramovich had his assets frozen, and a genuine sense of financial armageddon loomed over Chelsea, they welcomed the newly Saudi Arabian-funded Newcastle to Stanford Bridge. As one club saw the downfall of their leader, another club had only just begun its relationship with theirs.

The Newcastle fans that travelled to London, no doubt, would have discussed the ramification of Abramovich’s sanctions. Amongst the more reasonably minded, there would also be concerns about the relationship that they have just gotten into themselves.

Some, for instance, would have had premonitions about Newcastle becoming mired in a political conflict themselves. Did the crisis at Chelsea, hypothetically hold a mirror up to their club’s own future?

Most will know Newcastle is now financially backed and owned by a consortium, governed by the Saudi Arabian state. Those with their finger on the pulse politically will also be aware that their government has been involved in waging an illegal war against neighbouring Yemen for the last seven years.

Parallels between the two clubs uncovered a certain hypocrisy in the media coverage. Vladimir Putin has been rightly condemned for his aggressive invasion of Ukraine, and the evidence appeared to show a strong link with Abramovich too.

But is the same not true of Mohammed bin Salman? This is a man who is unambiguously responsible for funding both Newcastle and the war in Yemen.

Moral conflict

Plenty in the media were not alone in looking the other way or downplaying the significance of where Abramovich’s money came from. There is a genuine question that could be asked of any fan, of any club, in the game:

How much would you be willing to compromise for a successful football team?

This is now pertinent to Liverpool after Fenway Sports Group placed the club up for sale, with the club’s valuation upwards of £3 billion only to attract a short-list of potential suitors.

For many fans, the success of their owners is solely based on the amount of investment they have made. Geopolitics is of much lesser concern. Some sympathy should be had for the decent supporters, who understand these moral implications from the outset but feel powerless.

But is that enough?

The attempt of FSG and other elite club owners to form the infamous breakaway Super League showcased the strength of fan power in the game when firm resistance ensured the idea was quickly squashed.

If the same passion had been placed in rejecting Abramovich, would he have been able to take over Chelsea? If Newcastle fans gathered en mass to reject the Saudi takeover, would it not have been a non-starter?

Perhaps the cognitive dissonance that a fan feels is overridden by other factors.

For many football fans, the tribal nature associated with their club is deeply entrenched in their psychology. It’s not just a club, it’s an identity. It’s a way of life. It’s a long and passionate love affair. Above all it’s not seen as a business, it’s much purer than that.

This can make it difficult, if not impossible, to remain impartial. In many ways, this can be trivial and largely unharmful: overestimating the strength of one’s own team, believing in some virtuous characteristic of their club, or claiming that their fans are the best in the world, for example.

But what if this bias allows for a decay of one’s usual moral standards?

It’s hard to imagine any person, unless they are truly psychopathic, believes that the killing of innocent people, including children, is acceptable. But that is the reality, and in the case of Newcastle’s ownership, it was well-documented during the takeover process.

Knowing a few Geordies over the years, and generally having an admiration for their humour and gregarious characteristics, it is hard to imagine this acceptance as being anything other than tribal biases – a human flaw which we all experience to some extent.

The nature of the game, however, has changed and there is no use denying it. The Abramovich situation made it abundantly clear that football and politics are related. Truth is, this has always been the case.

When Shankly talked about his vision for socialism in the 1980s, it was set against an increasingly individualist UK, with former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher infamously saying, “There is no such thing as society.”

And she showed contempt for the working class throughout her time in office. People connected with the Hillsborough disaster were certainly not greeted with condolences from Thatcher.

Instead, they were left to deal with a barrage of false accusations, including being blamed as the “drunken louts” responsible. It wasn’t until April 2016, that a jury found those who lost their lives had been “unlawfully killed” and the “behaviour of the Liverpool fans was not responsible” for the disaster.

In those times football fans experienced what could be described as class war. The politics of the day and the increasing influence of foreign states have seen the game morph into a complicated business which is wrapped up in geopolitics and money.

These are the uncomfortable truths if fans are willing to rise about their own club allegiances.

It often gets said that football is only a game, but the evidence suggests it is far more serious than that.

* This is a guest article for This Is Anfield by Andrew Ramsay. You can follow Andy on Twitter @Andy__Ramsay.

Fan Comments