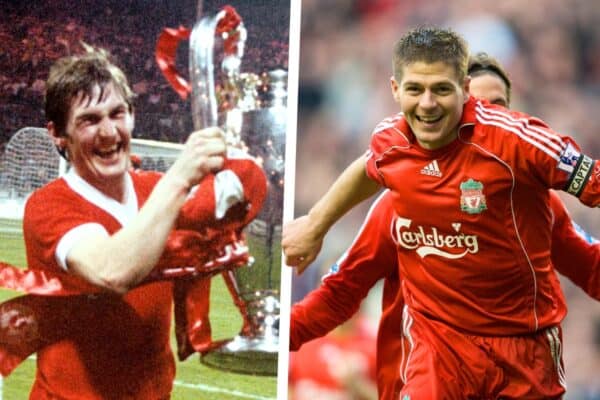

Thirty years after Liverpool’s 18th league title was delivered, the Reds still await number 19 – something nobody at Anfield would ever have entertained back in 1990.

Of course, it wasn’t meant to be this way and without the coronavirus pandemic Liverpool would have won the Premier League and we’d all be looking forward to watching Jordan Henderson‘s trademark trophy lift shuffle later next month, followed by scenes similar to those last June after European Cup number six arrived on Merseyside.

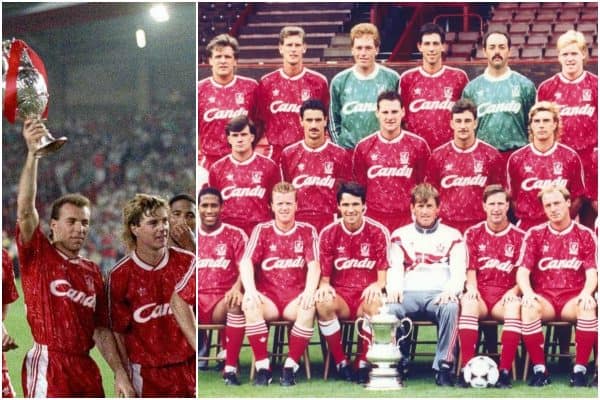

It was a different story back in 1990, when the title was officially won with two games to spare after Kenny Dalglish’s side beat Queens Park Rangers 2-1 and rivals Aston Villa drew 3-3 with Norwich City.

A tenth league title in 15 seasons meant the celebrations on the day were fairly low-key. Nobody among the 37,758 inside Anfield would ever have imagined a three-decade drought.

“You wouldn’t have believed that we wouldn’t have won a title for three years, never mind 30 years,” recalls defender Barry Venison to This Is Anfield.

“After the game, it was the same scenario: every time Liverpool had success, you had Ronnie Moran on top of you in the changing room saying ‘remember, bigheads, it’s done now, you have pre-season coming up, we need to go and win it again’.”

The trophy presentation after a routine 1-0 win against Derby County at Anfield three days later was fairly muted, captain Alan Hansen‘s trophy lift far from the joyous scenes of Madrid or Istanbul.

“It felt as if it was something we achieved every single year,” Liverpool club statistician Ged Rea tells us. “I think we took it for granted. It was never a case of could we win it, it was a case of when would we win it.”

Venison had signed for Liverpool four years earlier, in summer 1986, arriving at a club who had just won their first domestic double under player-manager Kenny Dalglish.

“He was obviously in the twilight of his career, but the ability, the vision, the drive and the cutting edge, being able to slice teams open and his link-up with Rushie: phenomenal,” Venison recalls.

“When you arrive, you have a dressing room of international players, top-class stars.

“The first thing you have to do is earn the respect of the dressing room. To do that you’ve got to perform in training every day. All the new lads that came in got battered verbally by Ronnie Moran. It was all part of the process that you were put through.

“That’s why the level of training was so good, because if you dropped your level or got injured, you’re not in that team. It’s the worst place to sit and watch all the fantastic stuff that’s happening on the pitch.”

Venison signed for Liverpool from Sunderland, where he’d made his name as the youngest-ever captain in a Wembley final aged just 20 in the 1985 League Cup final.

A year later, with Sunderland heading for relegation and his contract up, Venison wrote to managers of every club in the first division.

“I wrote to every club with my stats and how many games I’d played; basic stuff,” he explains. “Did that get me the move? Did that make Kenny pick up the phone? Absolutely not. I just wanted to do something extra.

“Kenny rang me out of the blue, I didn’t believe it was him, and the next day I drove to Southport and he asked me to sign. Fantastic.”

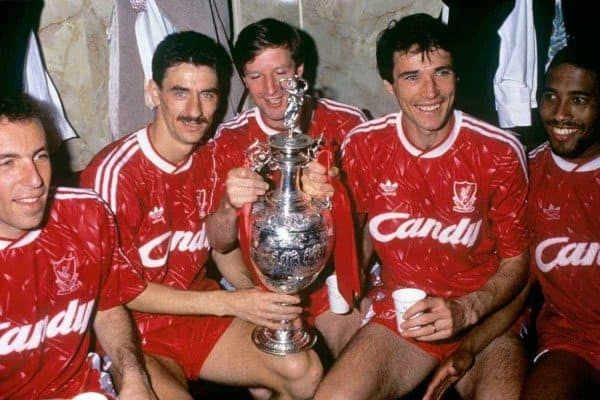

The squad

“When you look at that squad that won the league in 1990, there were a couple of standouts,” says Venison, who played 37 times in the 1989/90 season.

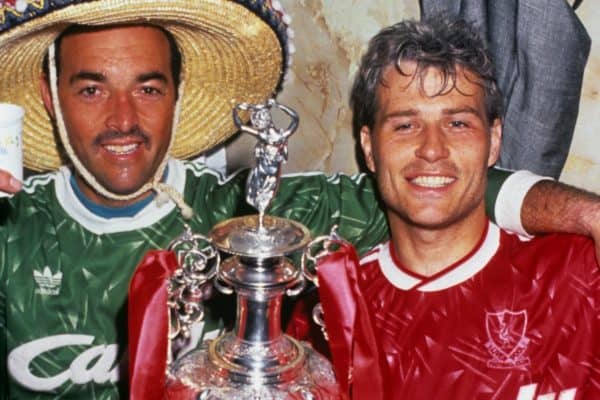

“Bruce [Grobbelaar]: absolute nutjob, on and off the field. Great fella, great character, more than a few screws loose, but what a great goalkeeper.

“Alan Hansen – Kenny was the manager, but they both ran the dressing room.

“He was the main man in the dressing room and in training. The quality and standards, he set the tone. Just a great leader, setting the level required on a day to day basis.

“He was such a good player, both as a defender and with the ball. In today’s team, it’s Virgil van Dijk.

“I didn’t realise how good Hansen was. You see Match of the Day and see Rushie banging them in, so no surprise there, but I didn’t know how good, instrumental and how strong a character he was and his standards every day.

“That was the single biggest surprise for me. He’s far better than anyone in the media ever game him credit for.

“[However] I’ve never seen a better defender in the league since Rushie. He was phenomenal at closing down. He covered more miles, at a faster pace, than he did hunting goals.

“He created so many goals for himself and teammates because of his relentless closing down. I played against him and it was a nightmare because he lets the goalkeeper throw it to you and by the time you’ve controlled it he’s on top of you like a rash.

“The best player I ever played with or against is John Barnes, without a doubt. The quality, the strength, the personality, a team player, oozing class, strong as an ox, good in both boxes, always stood up – he’s one of the best players Liverpool has ever seen.

“I’ve not even mentioned Ronnie Whelan, Steve McMahon, Jan Molby – one of the best passers I’ve ever seen – and Steve Nicol, which is absolutely rude – and Ray Houghton. You go right through that squad and you’ve got real top class people and professionals.

“The word winners is overused, but they were a group of high quality people who believed in the same thing at the same time. It wasn’t for portions of games, or one game, but for the duration of the season.”

Where did it go wrong?

So just how did this dominant machine go from winning 10 titles in 15 seasons to zero titles in 30 years?

Venison is perhaps perfectly placed to assess this, having been at the club from 1986 to 1992.

1987 saw the arrival of Barnes and Peter Beardsley to form what many believed was Liverpool’s most entertaining and exciting team of 1987/88. But two years later the warning signs were there, with the average age of Liverpool’s squad on the night that number 18 was secured being 28.23 years.

“There’s no one reason, but lots of different factors,” says Venison.

“The way Liverpool did it for decades was absolutely the right way because the trophy cabinet tells you that, but other teams like Man United and Arsenal were evolving and developing in different ways and Liverpool maybe didn’t catch up.

“After 1989 [Hillsborough], Kenny and Marina did so much for the city of Liverpool, and it sucked the life out of Kenny because he gave so much.

“Then Graeme Souness came in. He took a job and saw it as an opportunity to say ‘let’s move Liverpool on and bring in another model’. He did that overnight, which meant a lot of big name players were out of the door and others came in.

“He wanted a change in training regimes and by his own admission he tried to do it a little bit too quickly and it didn’t work out.

“They never really got back to being close to competing for the league after that for a few years, but should they have won it since then? Of course they should. They should have come back quicker than they have, no doubt.”

30 Years…

Following that 1990 title win, Liverpool finished sixth in consecutive seasons, then a 31-year low of eighth-place. Then came the dominance of Man United, overtaking Liverpool’s title haul, followed by the riches of Roman Abramovich and later Manchester City‘s Abu Dhabi-fuelled emergence.

Now, Liverpool have a new type of challenge: coronavirus.

“If they get denied the opportunity to officially win, that is catastrophic and shouldn’t be allowed to happen,” says Venison.

Fortunately, the Premier League is expected to resume in June, but that will almost certainly see Jurgen Klopp‘s side win the title in an empty stadium.

“This is a unique time, so you have to do what’s needed,” Venison assesses, pragmatically.

“If you have to go through the inconvenience of the lacklustre or deflating side of it, playing in front of empty stadiums, you don’t want that but you have to do it or you’re not going to lift the trophy.

“Liverpool have always been like that, pragmatic and nothing flash. If it’s a horrible ugly 0-0 and you squeak one in in the last minute – 1-0, three points, we won. That’s what Liverpool have to do and lift the trophy, and they’ll do it.”

The hope is that the deflating end to what should have been a memorable season for all the right reasons provides the Liverpool squad with reason to ensure it’s repeated in the correct manner the following season.

“I don’t see any reason why they can’t win it next season, too, and for years to come,” says Venison.

“They’re in a real good place, the feeling of togetherness, the hunger and love of the manager, the mutual respect. There’s a lot of similarities [to during the ’80s].

“When I look across the rest of the league, I don’t see any team who I think Liverpool need to beat when they play them, but every team needs to make sure they beat Liverpool.”

A 30-year drought will end in an unprecedented time, but in a post-corona world Liverpool’s ‘bastion of invincibility’ will ensure it isn’t another 30 years before the next title arrives at Anfield.

Fan Comments