On Armistice Day, LFC historian Kieran Smith reflects on the life of Liverpool striker Wilfred Watson – one of the final signings of the club’s longest-serving manager Tom Watson – who was sadly killed in World War I.

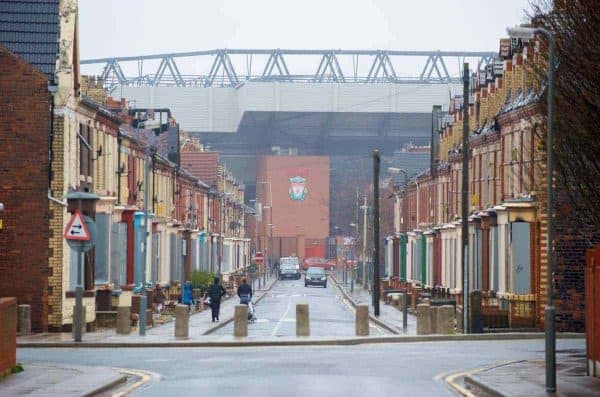

It is late August 1922 and the sun beats down on Anfield Road. Bert Riley, the Anfield groundsman carefully tends to the lush green pitch.

As you make your way through the hallowed halls of Archibald Leitch’s main stand, you notice a well-dressed gentleman carrying a bundle of papers. The smell of tobacco begins to grow stronger and as you both approach an open doorway, he glances back at you.

The man is George Patterson, the Liverpool secretary, and amongst his paperwork are some handwritten notes given to him by Dave Ashworth.

Liverpool are to face Arsenal at Anfield in a few days and the room you are about to enter is the boardroom.

Mixed in with the tobacco smoke is the smell of fresh rabbit pie, the homemade speciality of Bert’s wife, Mary Riley, and a favourite of the directors. The gleaming silver First Division trophy stands proudly amongst a selection of trophies, cups and pictures that adorn the room.

As you walk in, a reflection appears on the well-polished boardroom table. The reflection comes from the frame of a picture hanging on the wall. This is not a team photograph or the portrait of a director.

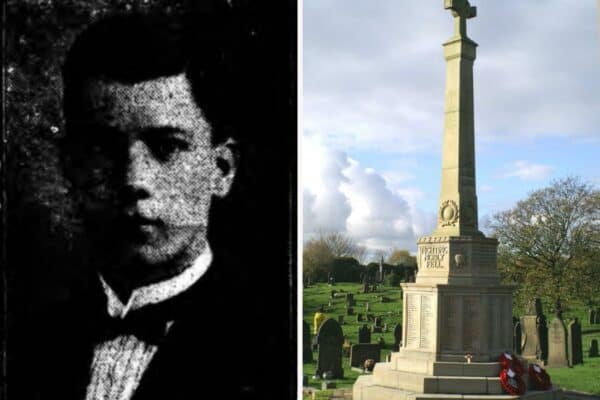

This is a photograph of a young man, a man by the name of Wilfred Watson, and this is his story…

Wilfred was born in the Lancashire mining town of Ince-in-Makerfield, to parents Thomas and Susannah.

Residing at 107 Manchester Road, the Watson family were a mere stone’s throw away from the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, which would have been heavily used to transfer goods at the time, particularly the transportation of coal to Liverpool.

As a scholar, Wilfred’s education came via the Ince Central Schools and he also attended Sunday School at Ince Parish Church. Wilfred’s father was a clogger and by the time of the 1911 census, Wilfred was an apprentice clogger in his father’s business.

As a teenager, Wilfred was clearly finding a growing interest in football, and like so many boys, joined his church team, which featured in the Wigan and District Sunday League.

One can easily imagine that his father made Wilfred’s boots, leaving Wilfred to ensure that they were kept in good repair.

With the Ince Parish Church football team, Wilfred played two seasons and amassed 100 goals. Clearly, Wilfred was destined for big things.

Wilfred entered the world of senior football with local side Atherton.

Wrestling was a popular spectator sport at Atherton’s ground, with hundreds attending bouts and whose local stars included Billy Diggins, Billy Charnock and Dick Walls.

But it would be the upcoming star centre-forward in the Atherton football team who would soon attract the biggest attention of all.

By the latter stages of 1914, the brilliant and astute Liverpool FC manager Tom Watson would make one of his final signings, as Wilfred registered with the Anfield side on November 12, 1914.

There was a great deal of optimism in the Liverpool Echo that day regarding the club’s new capture, and Ernest ‘Bee’ Edwards, the newspaper’s popular sports editor, wrote excitedly about the capture, reflecting on Wilfred’s goalscoring prowess and speed.

According to the article, there was also interest from Bury and Blackpool, but Liverpool would be the new home of this up-and-coming centre-forward. Ernest concludes his article: “Watson of Liverpool is expected by manager Watson eventually to do the club much good.”

Britain had declared war on Germany earlier, on August 4, 1914. The football season was allowed to continue, in its entirety, with Everton securing their second Division One title and their first at Goodison Park.

As the war in Europe unfolded, more men were joining the armed forces, and this included an increased number of professional footballers.

It was becoming clear that the professional game could not continue. Therefore, professional football was suspended, players took on amateur contracts and the league format was altered to accommodate regional leagues.

Liverpool were to play in the Football League (Lancashire Section) in 1915/16.

Wilfred had started to make a name for himself in Liverpool’s reserve side and on October 30, 1915, he featured in the Liverpool first team as they faced Man United, as well as the Lord Mayor’s Roll Of Honour Fund charity game against Everton in May 1916.

A little over two weeks after this game, Wilfred was called up for service and the Western Front beckoned.

On May 23, 1916, Wilfred joined the Royal Garrison Artillery as a gunner, enlisting at the Number 2 Depot (Heavy & Siege) at Fort Brockhurst in Gosport.

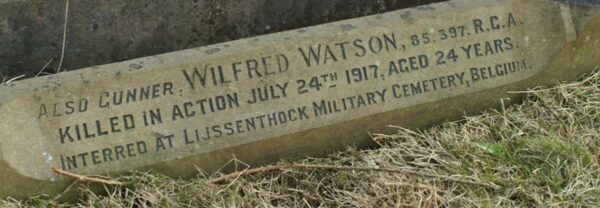

He was assigned service number 85397, with his attestation paperwork detailing his age as 23 years and 279 days and a height of 5’8”.

The 174th Siege Battery was raised at Weymouth, Dorset on June 13, 1916, the date that Wilfred was posted to that location.

He was soon granted leave and played for Liverpool against Oldham Athletic on September 16. The following week Wilfred was posted to the “A” Siege Depot in Shoreham on the South Downs.

During this posting, he obtained 1st Class in signalling and telephony, something that he was to put into practice in the trenches.

The 237th Siege Battery left Southampton on January 23, 1917, and arrived in the French port city of Le Havre the following day. Given the harsh winter conditions, the 237th Siege Battery was slow-moving, as the men carefully manoeuvred 4×6-inch Howitzers, weighing in at almost 4,000kg each.

Initially, they took a position in the convent at Ypres.

The intensity of the shelling at this location led to three of the guns being destroyed. This forced the battery to move position again, this time to Brielen Farm, remaining here until early April 1917, when they joined the 88th Artillery Group near the Belgian village of Vlamertinghe.

By mid-June, the 237th joined the 71st Heavy Artillery Group.

From Wilfred’s records, March 1917 saw him become involved in the role of wireless telegraphy. This could be a very hazardous role, as men dodged bullets and heavy artillery as they laid landlines.

On July 24, 1917, Gunner Wilfred Watson was injured as the area came under attack. Obtaining serious shell wounds, Wilfred was transferred to the 17th Casualty Clearing Station, located at Remy.

Sadly, he was to succumb to his injuries here on the same day.

Wilfred was laid to rest in the military cemetery at Lijssenthoek, which would become the second-largest Commonwealth cemetery in Belgium.

The Wigan Observer and District Advertiser, dated Saturday, August 11, 1917, included the news of Wilfred’s passing, along with several other local men.

His sergeant conveyed on behalf of the signallers how generous and great-hearted he was, as well as the love he had for his family. Three days later the same newspaper conveyed the feelings of Liverpool FC, describing his popularity and the deplorable news of his death.

Later that year, his father acknowledged the receipt of Wilfred’s personal effects: a simple note listing a nine-carat gold signet ring, engraved ‘W.W.’ and a wrist strap.

As his father opened that package and held his son’s signet ring, a mix of pride and deep sorrow no doubt raced through his mind.

A few years later, the family would receive his British War and Victory medals as well as the Next of Kin Memorial Plaque and Memorial Scroll. Issued as a means of providing families with a tangible memorial, it may have been the closest many would be to having a grave to their fallen relative.

The family grave in Ince includes Wilfred’s details, and the local war memorial lists his name, proudly and sombrely along with so many others.

After leaving his hometown for the front, his school gave his parents the gold medal that had been awarded to him for 14 years’ regular attendance and good conduct.

Like so many of his generation, we will never know what life he would lead.

We can imagine his time at Liverpool, having survived the Great War, as part of The Untouchables, playing alongside the likes of Elisha Scott, Tom Bromilow and Harry Chambers, securing his place as a legend, his selection for England games and becoming a Kop favourite.

Regardless of his short time at Anfield, Wilfred Watson is remembered by the Liverpool FC family.

* This is a guest article for This Is Anfield by LFC historian Kieran Smith. Follow Kieran on Twitter, @lfchistorical. Images courtesy of playupliverpool, David Long and the International War Graves Photograph Project.

Kieran Smith is the co-author of the new book ‘The Untouchables: Anfield’s Band of Brothers’, along with Jeff Goulding. You can purchase via Pitch Publishing here.

Fan Comments