Author Tom Whitworth speaks to those who witnessed Liverpool FC’s struggles of the 1990s as the Reds were removed from their pedestal.

An extract from ‘When the Seagulls Follow the Trawler: Football in the 90s‘.

‘Mr Nice Guy’

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Liverpool were the dominant force in English football. After Bill Shankly (who won six major trophies with the club), there was Bob Paisley, then Joe Fagan, then player-manager Kenny Dalglish. Between them, they guided the Reds to trophy after trophy. From 1975 (Paisley’s first season in charge at Anfield) to 1990, their honours list read: ten First Division successes, two FA Cups, four League Cups and – chests out to the continent – one UEFA Cup and four European Cups.

Under Dalglish, the dominance lasted until about 1989, the year of Hillsborough, after which the club began to lose its way. Dalglish left in 1991, the strain and stresses of the job compounded by the trauma of what he witnessed in Sheffield. Nobody at the time would have believed that Liverpool’s First Division title win in 1989/90 would be the last the club would win for 30 years.

After Dalglish, the job was handed to Graeme Souness, Liverpool’s successful captain of the 80s who had epitomised the dark hair, moustached and short shorts-wearing footballer of that era. As manager of Glasgow Rangers, Souness had led the Ibrox side to three Scottish league titles. At Liverpool, as football was changing from ‘Old’ to ‘New’, he sought to change and modernise the club. Attempts to influence improvements to player diet, for instance, were well-intentioned – perhaps ahead of the curve in the very early 90s – but poorly executed. ‘he tried to take on too much too soon,’ one of his players would remember of his approach. ‘he was very aggressive. he was having wars with everybody when he didn’t need to, really … If he’d gone in there with a feather instead of a sledgehammer, he might have been more successful.’

The players Souness brought to Anfield included Dunfermline’s Hungarian midfielder Istvan Kozma (who played just six times), Danish defender Torben Piechnik (17 appearances) and West Ham’s pragmatic left-back Julian Dicks. But this was Liverpool, the leading English club of the past few decades, and signings like that simply didn’t meet the standards of the past. As Manchester United were taking the nascent Premier League by storm, Liverpool drifted and in 1992/93 finished sixth.

In 1992 Souness underwent triple heart bypass surgery and afterwards he ill-advisedly sold his post-op interview to The Sun. The interview was considered deeply insensitive to the victims of the Hillsborough disaster and their families following the stories that that newspaper had printed in its aftermath – namely its ‘THE TRUTH’ headline and the false accusations of Liverpool fans stealing from victims as they lay on the pitch, and that they had assaulted police officers. To this day the boycott of The Sun continues on Merseyside and after his interview Souness’s reputation in the city was markedly tarnished.

Through the 1993/94 season, attendances at Anfield averaged just below 36,000 and after First Division Bristol City knocked his Liverpool out of the FA Cup in January 1994, Souness resigned from his post. Promoted in his place was Roy Evans, a Liverpudlian who for almost 30 years had loyally served the club as both player and coach.

–

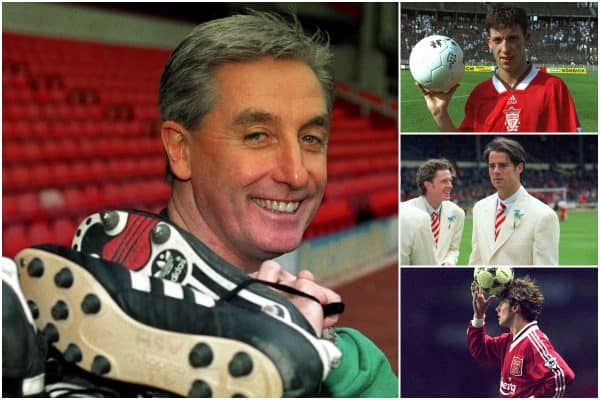

Now aged 69, Evans has invited me to his house on the outskirts of the city to talk about his time in charge of the club in the 1990s. White-haired and clean-shaven, a top-class man who they used to call ‘Mr Nice Guy’, he greets me with a smile and a handshake.

‘As a player I could have gone to Everton, Tottenham, Manchester united,’ says Evans, settled down in his living room, ‘but Liverpool was my club so I joined them in more or less 1965. I went right through the system and after a couple of years got through to the reserves. I hit a bit of brick wall trying to get into the first team because they were so good at the time [Evans would manage 11 appearances for the first team over the next few seasons].

‘I was still only 25 when I was offered a job on the coaching staff. Shankly had just retired and Paisley had taken over and he offered me the job. I refused at first because obviously at that age I was being told something I didn’t really want to hear – that I wasn’t going to be making it into the team. But they asked me a few times and eventually I ended up taking it. They let me run the reserves as my team for almost ten years, pretty much how I wanted. After that I was first-team coach for Joe Fagan, then assistant manager under Souness. I felt I’d done all the jobs and had a good idea about what was going on at the club.

‘When Graeme left, I went round to the chairman’s house [David Moores] and he offered me the job. I accepted of course. I didn’t ask how much I would get paid or anything like that, I just said “Yes”. When I got back home, that’s when I started to get the enormity of it. I had all the responsibilities in my shoes now.’

With the club sitting fifth in the Premier League table, Evans had a job to do to bring Liverpool back to their former heights.

‘Obviously over the years we were used to being a successful club. Graeme had come in and it hadn’t quite gone right. he had some good ideas and obviously I was part of that as his assistant manager. But you’ve always got your own views and from that point I was able to put my own ideas into it.’

Key to Evans’s philosophy was to get the team playing good, Liverpool football again.

‘I wouldn’t say that we had moved that far away from it. Shankly had the view that simplicity was genius and I think that that really worked. Other things like pass to the nearest red shirt were good ideas too. It was all about keeping the ball while people were trying to move and get into different areas of the pitch. Pass and move. So I tried to bring us back to that.’

In 1993/94, Evans would guide Liverpool to an eighth-place finish in the Premier League and the season after was able to put more of a stamp on things. In came the defenders John Scales (£3.5m from Wimbledon) and Phil Babb (£3.6m from Coventry City). Out went midfielder Don Hutchison and the Souness signings Dicks and Piechnik. ‘Graeme had left us with some guys who were quite physical but not the most talented,’ Evans explains.

‘Fortunately there was a good flow of good lads coming through the system at the time. We still had the experienced players like John Barnes and Ian Rush and then the younger lads to work with them.’ The crop included goalkeeper David James, defender Rob Jones, midfielder Jamie Redknapp and locally born forward Steve McManaman.

That season, 1994/95, Evans deployed a 3-5-2 system as opposed to the more standard 4-4-2 used across the Premier League at the time, with his wing-backs bombing forward on either side of the pitch. Liverpool finished fourth in the league and won a trophy. Against Bolton Wanderers at Wembley in the final of the League Cup, McManaman blossomed in his free role behind the strikers as he scored two terrific dribbling-and-striding strikes in the 2-1 win.

‘McManaman just had the ability to go past people and was very straightforward with it,’ says Evans. ‘He wasn’t all step-overs. It was cut inside, head up, pace. Once he was past that back four and the defenders were running back he was making chances. He was a great asset for us.’

Also emerging alongside McManaman and the rest of that younger group was another exciting player, from the south of Liverpool, who in 1994/95 had topped the scoring charts with more than 30 goals in all competitions.

Backs to the Country

July 1981. In the Liverpool district of Toxteth, frustrations over high unemployment and poor relations between police and the community’s predominantly black population had erupted into violent riots. That year, 20 per cent of people were out of work in the city, more than the double the national figure, and during those nights of violence hundreds of arrests were made as hundreds of rioters and police were injured. People from different parts of the city had joined in and buildings and cars had burned. Just as Toxteth was the stage, the longstanding frustrations of a city’s population were the story.

In the aftermath of the riots, the Conservative MP Michael Heseltine was dispatched to the city to walk the streets to try to understand what had gone wrong. While Margaret Thatcher’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Geoffrey Howe was suggesting the ‘managed decline’ of troubled inner cities like Liverpool (‘I fear that Merseyside is going to be much the hardest nut to crack’, Howe said of the region specifically), Heseltine pressed for a path based on urban development underpinned by both public and private investment. The regeneration of the Albert Dock was one such showcase example.

The overtures of Heseltine were set against the backdrop of the activities of the city’s Labour council, which included a number of hard-left Trotskyist Militant members. After winning power in 1983, they went on to set an illegal, loss-making budget for the city – effectively giving the finger to central government – and 47 of its councillors were expelled from office.

‘I remember it [Toxteth] as being a safe enough place to grow up, and I didn’t remember ever having much trouble as a kid,’ the Liverpool star Robbie Fowler would write in his 2005 autobiography of the area he grew up in. ‘There were always places you shouldn’t go, and people you should avoid, but the fact is, you didn’t go far at all anyway.

‘[A]t one end of my road was the school, and at the other end was an all-weather football pitch, and for me, that was the extent of my world … I don’t remember much about it [the riots], because I was too young [Fowler was six at the time] … too little to understand … but I do know it happened right outside our front door … on the pavement right outside my front door, about ten feet away from where I was watching the telly.’

Fowler was born in 1975 and joined Liverpool’s youth set-up when he was 16. Left-footed with superb striking technique, he was a devastatingly accurate and prolific in front of goal. By 17, he had made his debut for the first team, scoring against Fulham in a League Cup tie at Craven Cottage. In the return leg at Anfield, he netted five times and afterwards celebrated at home with a can of Irn Bru. In his breakthrough 1993/94 season, Fowler scored 18 times.

The young striker played with enthusiasm and a smile on his face. The following season against Arsenal at Anfield in 1994, he hit a wonderful five-minute hat-trick – three of his 31 goals that season. he was the undoubted star of Evans’s emerging side, representing along with McManaman and Redknapp its fresh-faced possibilities. Fowler would be especially adored by the Liverpool fans who in time would call him ‘God’.

During 1995/96, he was unstoppable again, this time with 36 goals. Against Manchester United at Old Trafford in October, when Eric Cantona returned after his kung fu kick ban, he hit two brilliant strikes. his first was a rocket at Peter Schmeichel’s near post, then came a delicate lob over the Danish keeper after he had firmly knocked the united defender Gary Neville out of the way. Later on that season at Anfield, against Aston Villa, Fowler scored one of my favourite goals ever: receiving the ball far out from McManaman and with his back to goal, he flicked it past Steve Staunton, turned and took it on with a touch before triggering the sweetest bending-away strike into the left-hand side of the net.

Roy Evans loved him. ‘Robbie, to be fair, is up there with the very best, with people like Ian Rush. he was Johnny-on-the-spot, always in the right position at the right time. If a loose ball came into the penalty area, he’d be there and would put it into the back of the net. That’s not something you can coach. It’s something that’s very natural. he had a very sharp brain and would take things on board that you said to him. And he scored great goals.’

Spice Boys

For the 1995/96, season Evans made two additions to his squad. he spent £4.5m on Bolton Wanderers’ Birkenhead-born Liverpool fan Jason McAteer. McAteer would be used by Evans as a right wing-back, able to push forward energetically and add to the team’s attacks. Then a club and British record fee of £8.5m went on Nottingham Forest’s striker Stan Collymore, a tremendously talented forward – powerful yet elegant – who on paper looked the ideal foil for Fowler.

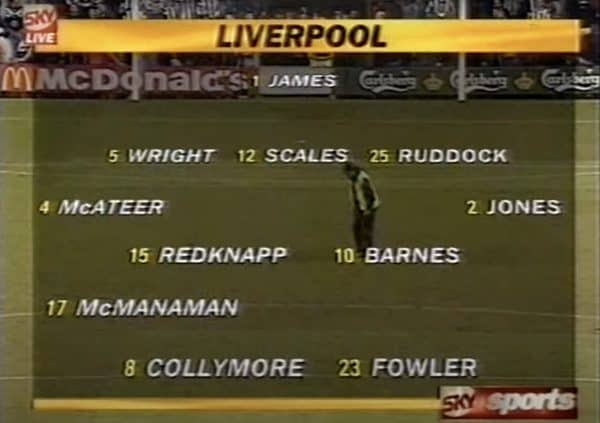

Evans now had Fowler, Collymore or club legend Ian Rush to pick from upfront. McManaman roamed in behind in his free role. Redknapp, John Barnes or Michael Thomas competed for the two midfield spots. Rob Jones was the wing-back on the left, McAteer on the right. Phil Babb, Mark Wright, John Scales or Neil Ruddock were Evans’s options for the three centre-back positions. David James stood behind them in goal.

By the end of October 1995, Liverpool sat third in the Premier League, five points behind Kevin Keegan’s pace-setting Newcastle side. So far they’d despatched Tottenham (3-1), Blackburn (3-0), Bolton (5-2) and Manchester City (6-0) with exciting, free-flowing attacking play. Fowler had reached ten goals. The author and Liverpool supporter John Williams would describe Evans’s emerging team as ‘the passing team in England in the mid-1990s’.

Then came what the VHS season review of that season (which on the cover featured Fowler wearing that year’s excellent green-and-white four-quadrant Adidas strip) would call ‘Black November’ – a torrid month in which Liverpool lost three times and drew once in the league, along with exiting the League Cup at Newcastle. ‘For some reason we had a really poor month’ remembers Evans. ‘That probably cost us the league that year. I don’t know why what happened or why. Sometimes you just lose that little bit of confidence. With the class of players we had it was very difficult to pinpoint, a little spell where we couldn’t score and we couldn’t defend. Sometimes it’s about mentality.’

Around this period there were disconcerting rumours surrounding the exploits of some of the Liverpool players, which, when added together, built up to a picture of indiscipline and casual attitudes, a lack of drive and determination and, perhaps worst of all considering the club’s rich heritage, unprofessionalism. These rumours and stories would help explain that team’s ultimate failings.

First there was the excessive drinking. While in the mid–90s such activities were still prevalent at many, if not most football clubs, Liverpool had their fair of alcohol-related stories at the time. There were tales of players leaving straight after home games to go out partying in London, or closer to home the big nights at Liverpool’s famous Cream nightclub. As Neil Ruddock would recall, ‘We had a saying, “Win, draw or lose; first to the bar for booze.”’

There were stories like the players passing around a £1 coin to hold during matches, with whoever ended up with the coin at the end of the game buying the drinks that evening. ‘There was one game when we were lining up to defend a free kick,’ Ruddock would remember, ‘and it [the coin] was being passed along the wall. We lost that one 2-1.’

Further to that, there were stories of punch-ups between players – Ruddock and Fowler, for example (or more specifically, Ruddock punching Fowler after a flight back from a European away tie). Or of Stan Collymore never quite fitting in with the squad – he would last only two seasons at the club before being moved on to Aston Villa. There were accusations over poor time-keeping – on one occasion Rob Jones was late for training because he had fallen asleep at some traffic lights. And in general, casual attitudes in training such as Ruddock (again) walking out on to the training pitch eating a bacon sandwich. Still to come were Jason McAteer’s Wash & Go television advert and David James modelling for Armani.

In July 1996 the Spice Girls had high-kicked their way into the music charts with their single ‘Wannabe’. By March 1997, for all of the fun they appeared to be having away from the football pitch, Evans’s group had earned themselves the nickname, the ‘Spice Boys’. It was all a bit Loaded magazine, lairy lads getting up to mischief. All a bit Dumb and Dumber.

‘I thought the whole “Spice Boys” thing was unfair,’ says Evans. ‘They were good pros, good lads and they all had a bit of personality. They lived a life outside of football. Of course the media is always quick to jump on anything that they think isn’t perfect. At that time the players were starting to stand out more, become more popular on the television, more popular than they’ve ever been. If you made a mistake or did something wrong, the press and the media was all over you. But I liked the fact they had a bit of personality.’

Liverpool is a working-class city, though, where its footballers are placed on pedestals. Expectations will always be high, particularly among Liverpool supporters. For a club with a heritage of such professionalism and winning, shenanigans like this did not match up with the standards of those times and of those levels. Around this time Premier League players were earning around £2,500 a week on average (a number of the league’s top players by now were taking north of £10,000) and Liverpool fans were paying good money to watch their team play at Anfield. As Jamie Redknapp would recall more critically of the situation at the time, ‘There were one of two things Roy [Evans] could have nipped in the bud sooner … We needed the iron fist a little bit more.’

–

After ‘Black November’, Evans’s side managed to recover and go on a 15-game unbeaten run in the league with Fowler scoring more of his beautiful goals: he scored two against Manchester United at Anfield in December – one of them a delicate free-kick that totally wrong-footed Peter Schmeichel. Two more came against Aston Villa in the semi-final of the FA Cup at Old Trafford. The first was a header and the second a left-foot half-volley floated into the corner of Mark Bosnich’s net. ‘You are looking at a goalscoring genius,’ the Sky commentator Martin Tyler said of that one.

Despite the upturn in form and the excellence of the likes of Fowler and McManaman, Liverpool still lacked the cutting edge of top teams of their past. Two games in early April highlighted their ups and downs and their inconsistency of the period. First at Anfield they hosted Keegan’s Newcastle who led Liverpool by five points in the league with a game in hand over them. The encounter is one of the Premier League’s classic matches where Liverpool had led twice and trailed once before eventually taking the 4-3 injury-time win. Three days later, they then lost 1-0 to relegation-threatened Coventry City at Highfield Road.

Liverpool would finish the season third in the table, their best finish for five seasons. Many believed they could have challenged harder and finished closer than the 11 points difference that ended up between them and the eventual champions Manchester united.

There would be one last chance of glory in the 1995/96 FA Cup Final against Manchester United. Despite Liverpool’s flaws, it was a contest that still promised so much, pitting two very good sides against each other for the season’s finale.

hours before kick-off, the BBC’s Des Lynam greeted the TV audience on Cup Final Grandstand with, ‘Good day to you from Wembley’. The coverage included clips of the teams at their hotel and of the supporters gathering on Wembley Way. The game itself was a poor affair, though, failing to live up to its hype. While on the day Liverpool at times looked comfortable on the ball, they weren’t able to make inroads to the United goal. McManaman was largely stifled as he was harassed by Roy Keane, and thus the supply to Fowler and Ian Rush was cut. In the 86th minute, Eric Cantona struck through a crowd of Liverpool players to win the cup and take the Double to Old Trafford.

‘We didn’t play, they didn’t play,’ recalls Evans of the big day. ‘unfortunately, they got the goal and that cost us the cup. Nobody really deserved to win it, but they scored the goal which we probably should have defended better. Obviously with it being two big teams everyone thought it was going to be a great game, but it wasn’t. It was a poor final.’

What the final would mostly be remembered for, though, were the cream Armani suits that the Liverpool players wore before the game. Journalist and Liverpool fan Brian Reade was unimpressed by his team’s infamous choice of clothing. ‘As they strolled around in their matching designer suits and shades, half of them looking like they were trying to be spotted by a modelling agency, we just looked on in shock and amazement,’ he would write in his book, 43 Years With the Same Bird: A Liverpudlian Love Affair. ‘Their get-up and their body language said everything we’d feared to speak about them. It said we want different things in life from you.’

That quote again from Manchester United defender David May about the suits Liverpool players were wearing that day, ‘We thought they looked like fucking knobs.’

* This is an extract from ‘When the Seagulls Follow the Trawler: Football in the 90s‘ – available to buy now.

Fan Comments